What’s Next for Michigan Forests After the Historic Ice Storm?

Michiganders can handle their share of winter weather. But the ice storm that hit the Lower Peninsula in late March was so severe and destructive that people have called it a “generational storm.” With an inch or more of ice building on branches for days on end, entire stands of pine, oak, and aspen in Northern Michigan snapped or buckled under the weight — as did power lines, poles, and other infrastructure. The storm caused widespread blackouts and led Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to submit a disaster declaration asking for federal aid.

Residents and state officials are still surveying the damage and working through the wreckage across millions of acres of northern woodlands, which are unrecognizable in some places and totally inaccessible in others. So what happens now?

Because of the overwhelming scale of the destruction, land managers say there will be noticeable effects to forest health, including higher risks for intense wildfires. These altered habitats will affect wildlife populations as well, although some critters might actually benefit in the long run, according to biologists. The biggest and most immediate impacts, meanwhile, are on outdoor recreation. The state warns that hunters and other users will continue to encounter blocked roads, closed accesses, and treacherous woods.

Recovery efforts, including salvage logging operations, are underway and will be for the foreseeable future. State officials say this will be costly, though, and as of May 20, the Trump Administration had not yet responded to Gov. Whitmer’s request for help.

Blocked Roads and Fire Risks

Roughly 3 million acres of forest in 12 counties were affected by the 2025 Ice Storm, according to initial surveys by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. That included around 1 million acres of state forest land, or roughly a quarter of the entire state forest system. The closest historical comparison in the area was the damage wrought by the Great Michigan Fire of 1871, which burned about 2.5 million acres of forest.

“It’s certainly the worst natural disaster that I’ve lived through,” says Michigan DNR public information officer Kerry Heckman, who lives in the affected area on an 80-acre wooded parcel that borders state forest land. “And because it lasted so long, it was almost a week of hearing nothing but trees coming down and branches breaking, almost constantly. It was very unnerving to be outside, but it was also disconcerting inside. You almost felt like there wasn’t a safe place to be.”

At one point a white pine just missed their house. Heckman and her husband spent the week without power, relying instead on generators while helping their neighbors cut out driveways, and praying that more falling trees wouldn’t hit their cabin.

“We wouldn’t even go out without a hard hat on,” Heckman continues. “You had to have a spotter, too, because if you have a chainsaw running, you might not hear a tree coming down right next to you.”

Read Next: Beginner’s Guide to Timber Stand Improvement: How to Manage Your Woods for Deer and Other Wildlife

It has now been two months since the storm. Heckman says the DNR has so far been able to assess around 150,000 acres, or roughly 20 percent of the affected acreage on state forest land. Foresters are still gauging the severity of the damage as they plan salvage and thinning operations, and much of the floor is still covered with downed branches, debris, and half-fallen trees that are hinged or hanging down — what Heckman calls “ladder fuels,” which can carry flames into the tree-tops and create hotter, faster-spreading wildfires. She says they’ll have to monitor and mitigate these risks for the next five to 10 years.

The agency’s biggest priority at this point, though, is clearing the more than 3,000 miles of state forest roads that were blocked off or damaged during the ice storm. Heckman says the DNR has focused on roads in fire-prone areas “because we don’t want to have to respond to a wildfire and not be able to get to it.” But crews are also prioritizing the main access roads that are used heavily by hunters and other forest users.

“The last time I looked, we had over 1,000 miles [of road] that were impassable. That’s like us needing to clear the roads from Mackinac City to Atlanta, Georgia.”

These efforts will continue at least through 2025, Heckman says, but progress is slow. Even the heavy equipment crews using skid steers and bulldozers are only able to clear about two miles of forest road a day.

Beware of Ankle Breakers and Widowmakers

Most of the state parks, campgrounds, and boat ramps that were closed as a result of the storm have since reopened. The MDNR’s website has an updated digital map that shows this information. But Heckman says that cabin owners and other people who frequent these woods to hunt, fish, forage, and hike will likely encounter closed roads, hard-to-reach areas, and other hazards.

“Just walking through the forest is difficult in places. There’s a lot of tree tops down, limbs down, and a lot of trees that are leaning,” says Heckman. “And aside from just traversing the forest floor, there’s also overhead hazards. There’s still a lot of widowmakers out there — trees or limbs that are hanging or caught up and can come down without warning.”

Those hazards could remain on the landscape through the fall deer season and into the winter months and beyond. And although public access will improve as more forest roads get cleared, hunters traveling off those main roads should remain wary.

“Whether you’re out turkey hunting or picking morel mushrooms, just be careful,” Heckman says. “Make sure you keep an eye on what you’re standing under, and what you’re trying to walk over.”

Wildlife Will Benefit in the Long Run

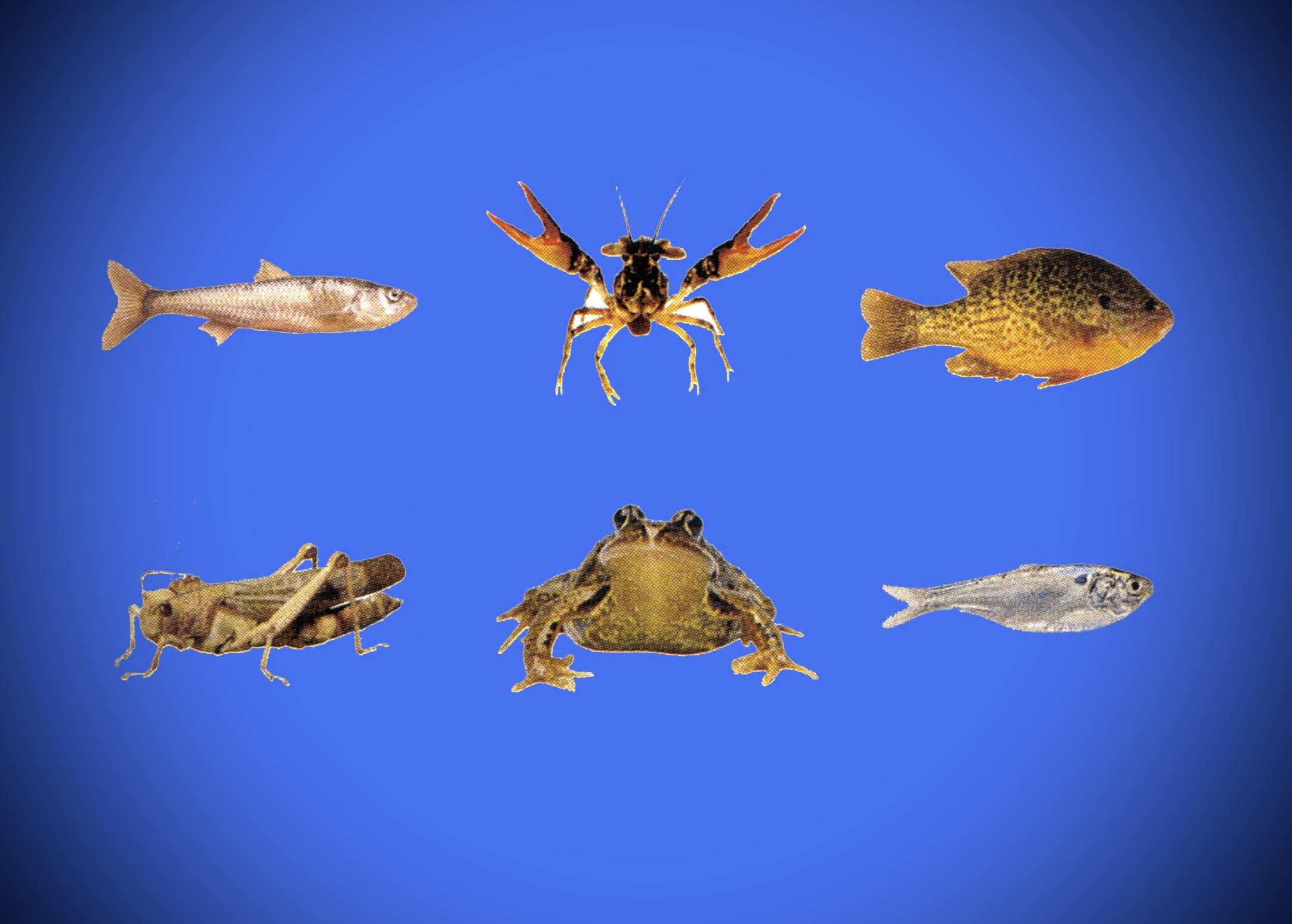

Fortunately for turkey hunters and mushroom hunters, there are still plenty of both species in the affected zones. In some ways, wild game and forage might actually benefit from the aftermath of the ice storm. (More on this in a minute.) Heckman says she expects a bumper morel crop in the coming years as woody debris decomposes on the forest floor. This woody material will also help create new and beneficial habitat for fish in local rivers.

Whenever historic storms like this strike, it often reminds locals of the last bad storm — and the damage it did. In one recent Michigan hunting forum, locals are retelling stories about winter storms in the 70s, and how they saw “hundreds of dead birds including many pheasants” that died on their roosts, some with “ice forming on their beaks.”

That doesn’t seem to be the case this year, according to Heckman, who has not heard any evidence from the field of wildlife dying in the storm. There were probably some animals caught under falling trees or that died of exposure, she says, but the idea of pheasants, deer, and other critters freezing in their beds and nests is more of a wives’ tale than a scientific reality.

There is some peer-reviewed research into the impacts that weather can have on Michigan’s game populations. According to one such study, harsh winters are one of the main limiting factors for the state’s deer herds.

Read Next: Why Is Deer Hunting in the Northwoods on the Decline? And Will It Ever Rebound?

However, MDNR biologist Shelby Adams told reporters in April that she thinks deer and elk populations in the area will actually benefit from the disturbance, which opens up the tree canopy and creates a flush of new growth. Along with whitetails, Northern Michigan is home to the largest free-range elk herd east of the Mississippi, and Adams said she expects to see even more of those elk in the areas damaged by the ice storm.

“We know there’s tops hitting the ground so the elk are taking advantage of that opportunity for this brief amount of time,” Adams told MLive. “As the forest regenerates in the next 10 to 15 years they really do thrive in that young forest landscape.”

Game birds like turkeys, ruffed grouse, and woodcock could benefit for similar reasons, Heckman says.

“We’re going to see a lot of those new plants and stump sprouts, especially from aspens. And that early successional habitat, ruffed grouse and woodcock love that. It’s obviously beneficial for deer as well,” she explains. “That’s actually a lot of what we’re trying to do when we do forest management, is mimicking that natural disturbance.”

Fortunately for wild turkeys, the ice storm hit well before their breeding and nesting season. So Heckman doubts the birds were impacted much by the event. Unfortunately for her, she was too busy coordinating damage control this spring to do any turkey hunting herself. Judging from what she’s seen on her own land, though, she has high hopes for next year.

“This is just anecdotal, but I actually saw more turkeys this spring than I have in a while,” she says. “We’re still seeing lots of wildlife in the area … we’ve seen deer on our game cameras, and I’ve actually had a bear and a bobcat on there as well since the storm.”

Read the full article here