We Wanted to Fly Fish, But the Trout Wanted Hellgrammites

This story, “It Takes a Grampus,” appeared in the August 1950 issue of Outdoor Life.

Did you ever buck a first-class, big scale, full-blown jinx in a choice piece of trout country? Ever fish streams where you knew from the looks of things there should be a good trout behind every rock, and where you had plenty of reliable testimony from residents to back your hunch, only to find the water as innocent of fish — hungry, co-operative, pugnacious fish, that is-as your bathtub back home?

It has happened to me in heavily fished country where there was a beaten, well-worn path along the bank of every creek. It has also happened in far-off, remote places where no other fisherman had wet a line in years. It happens to every man who surrenders himself to the mystic enchantment of trout water-but each time it happens to you it’s a heck of an experience.

It was happening to Mac and me that hot, early-summer day in the Great Smoky Mountains of eastern Tennessee, and we weren’t liking it one little bit!

We were in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park for a long week end to try those wild, rock-shredded mountain streams, and to contrast them with the clear, cedar-bordered creeks we knew in Michigan and Wisconsin. We wanted to learn for ourselves whether a foot-long rainbow caught in the shadow of the blue-hazed Smokies is the same bucking, tail-dancing, mad dervish of a fish as a rainbow of like size from a dark pool within hearing of the Lake Superior surf.

But all we had learned so far was that a trout’s will is his own. He rises when he feels like it and sulks when he prefers, and when he chooses to sulk there isn’t much anybody can do about it.

For two days the trout of Ramseys Prong and Roaring Fork, in the mountains above Gatlinburg, had sat tight in their watery lairs, refusing dry flies, wet flies, and nymphs with a stead fastness that was maddening. In the two days we hadn’t taken enough fish between us to cover the bottom of a one-man skillet, and those we had taken were so small that Mac commented bitterly they should have stayed in kindergarten another year!

Finally the truth forced itself upon us. We had come the long way down to Tennessee on an important mission — and somewhere along the road Lady Luck had put a curse on us, but good. We’d both had the same thing happen often enough before to know what it meant. We might as well sit down and smoke our pipes with tranquility and resignation, and forget about Smoky Mountain trout.

We came down from Roaring Fork the second night resigned but resentful. We had taken a total catch of five trout that day, barely legal keepers. After supper we dropped in to relate our tale of woe to the park ranger.

He heard us through with a sympathetic grin, but he didn’t agree with our size-up of the situation. “I don’t reckon you’re really jinxed,” he protested. “Maybe you just need a change of scenery. Why don’t you drive over into Cades Cove in the morning and fish Abrams Creek? There’s no better rainbow stream in the park, and all the fishermen that went in there last week took good catches. It’s a kind of outof-the-way place, and maybe the trout won’t know they’re supposed to be on a hunger strike.”

Mac and I were ready to grasp at straws by that time. We took the ranger’s suggestion the way a ship wrecked sailor goes for a life raft.

The road into Cades Cove turns off the main highway at Kinzel Springs, rises in sweeping loops through a range of wooded foothills, dips across a wide valley and then climbs abruptly into the Smokies by a series of oxbow bends and switchbacks. It’s one of the steepest grades I’ve ever climbed in a car.

Mac and I topped out on the ridge that morning after a climb that was head-spinning for men unused to mountain driving. At a place where wild azaleas made a patch of salmon-colored flame on the mountainside, we stopped our car and stepped out for a look down into Cades Cove.

I doubt there is a prettier spot in all the southern highlands. The cove is a couple of miles wide and maybe five miles long, locked in by wooded mountains all around, level-floored and green, a small island of farmland in the dense wilderness of the Smokies.

Closed at both ends by ragged peaks, no road enters it save the one we had followed. There’s no easy way to get in or out. We could see cattle and sheep grazing in the tiny patchwork squares of fields far below us, and a lazy blue curl of smoke rising from the mud-and-stone fireplaces of a couple of mountain cabins.

Twenty-five years ago some 500 people lived there in a close-knit community of mountain folk, milling their own flour, spinning and weaving their own clothes, splitting shakes for their roofs, cobbling their own shoes. Now fewer than a dozen families are left.

“Gosh, what a spot!” Mac exclaimed. “We’ll get some fishing down there!”

“I’m not so sure,” I retorted. “I like the looks of the place as well as you do, but I can’t say as much for the weather.”

Up to that time the June morning had been warm and clear and fine. But now ominous dark clouds were beginning to gather along the ridge on the far rim of the cove. While we watched they mounted swiftly higher, and far off thunder rolled and rumbled through the mountains.

Mac shook his head sadly. “If only it’ll hold off for a couple of hours!”

But the curse was still on us, and the storm didn’t hold off. It caught us just as we came off the mountain, a vicious thundershower that slashed its way across from one rim of hills to the other in a matter of minutes and all but blotted out Cades Cove in a silver curtain of rain. Mac and I knew that our fishing trip had blown up in our faces, but we decided to see what Abrams Creek looked like, anyway.

We pulled up at the side of the road and waited until the shower passed. Then we stopped in front of a cabin that showed chimney smoke, to inquire our way. We had less than a mile to drive. In a little rain-drenched clearing at the head of the cove we found four cars parked beside the road. At least we were not the only fishermen foolish enough to climb the mountain for the sake of a few trout!

I’ve seen some pretty footpaths side trout streams in my time, but nothing to match the trail we followed along Abrams Creek that morning. Mountain laurel hung over it in masses of pink and white bloom and here and there great clumps of purple rhododendron were coming into flower. We walked half a mile, with the sound of fast water in our ears most of the way, crawled and clambered down through the dense laurel hell that bordered the creek-and stepped into a trout stream out of a picture book!

It rushed and gurgled and tumbled over boulders and shelves of rock, it danced and glinted in the June sun, it had a distant backdrop of smoke-blue peaks, and it ran between solid banks of blossoming laurel.

“It’s like fishing in a flower show,” Mac said, and it was. But that’s all you could say for it.

If there were trout in that laurelshaded water they certainly weren’t feeding. We fished patiently and pains takingly for an hour, upstream with dry flies and downstream with wet. Mac went over to nymphs, and when that did no good he tried a favorite sure-fire formula of his, fishing a wet whirling Blue Dun in nymph style. It still did no good. We had gone back to dry patterns and were working upstream, belt-deep in the clear cold current, when we met two men splashing around a bend.

They showed plain evidence of the drenching the shower had given them, and they were no longer fishing. But their creels sagged suspiciously and they didn’t look exactly wretched. They stopped to chat.

I They were from Knoxville and they introduced themselves as Drum and Steve. I suspected they knew Abrams Creek from long experience, and when they opened their creels I was sure of it. They had eleven trout between them, all rainbows, the biggest fourteen inches, the smallest ten.

“We caught ’em before the rain,” Steve explained. “They quit as soon as it started to thunder and they don’t seem to want to start again.”

“What were they taking?” Mac asked.

“Minnows, mostly,” Drum replied with a grin.

“But you fellows are using flies,” I protested. “And anyway, I thought the ranger back at Gatlinburg told us it’s illegal to fish with minnows in the park.”

“It is,” Steve agreed, “and we didn’t take these on minnows. What Drum means is that the rainbows in this creek would rather gobble up a minnow than anything else. If a man could use minnows he’d sure make a killing. You open up one of these trout and the chances are he’s stuffed with ’em.”

He reached for a pocketknife and hauled out the biggest rainbow in his creel. He slit it down the belly deftly and laid open the bulging stomach of the trout.

It contained no minnows. What rolled out, instead, were three fat, full-bodied hellgrammites in various stages of digestion. I shuddered in spite of myself.

“I’ll be darned!” Steve grunted. “Grampuses! So that’s what they wanted this morning. Well, there’s no law against using a grampus in the park.”

I shuddered again. I’m not finicky. I have threaded my share of strange and distasteful baits onto a hook. But there are two at which I have long balked. They are the catalpa worm, as it’s baited inside out for bluegills on the lakes of Indiana, and the hellgrammite.

I don’t like hellgrammites. Mac studied the evidence thoughtfully and without any sign of squeamishness. But he’s a fly fisherman at heart and he wasn’t convinced.

I’m not sure myself why I feel the way I do about the hellgrammite. Maybe it’s the way his legs wiggle, or the fact that he has too many of them. Maybe I just have a phobia. Anyway, I don’t like hellgrammites.

I could see that Mac didn’t share my feelings. He studied the evidence thoughtfully and without any sign of squeamishness. But he’s a fly fisherman at heart and he wasn’t convinced.

“This grampus business may be all right,” he conceded finally, “but if you don’t mind telling us, I’d still like to know what you took these trout on.”

Drum and Steve chuckled. “Sure, we’ll tell you,” Drum agreed. “We don’t say much about it, but you don’t live in these parts and we don’t mind letting you in on it. We do most of our fishing on this creek with a yellow nymph. It’s one we tie ourselves. Looks a little like a peacock-herl nymph, only we give it a twist of our own.”

He reached into his fly box. “Here, try them,” he invited, and held out four of the hybrid nymphs. Mac didn’t exactly jerk his hand back.

Steve and Drum climbed the bank through the laurel and we went back to our fishing. We realized our chances were still slim, so soon after the thundershower, but it was close to noon now and we didn’t want to lose any more time.

We fished another hour. We sank those nymphs behind a hundred promising rocks and in countless eddies. We maneuvered them into shaded holes under overhanging laurel thickets along the banks, we fished them in the deep water of midstream. We put them in every spot where experience and common sense told us trout might be lurking, and we did our best to make them behave the way real nymphs are sup posed to behave. But our score stayed at zero. Lady Luck had hung one on us in dead earnest this time.

Mac Outboxes a Rainbow

Mac worked out of my sight around a bend. When I saw him again he was no longer fishing. He had laid his rod aside and was down on his knees in shallow water close to the bank, turning over stones and probing around on the bottom like a robin after a worm. He made a sudden pounce as I came up to him, and held up an evil-looking flat creature with a row of legs crawling repulsively the full length of its body on either side.

“A grampus!” he announced with a triumphant grin.

I shivered again. “A damned hellgrammite!” I snorted. “You can have him.”

“Wait and see,” Mac warned. “You’ll be grampus hunting before we quit.”

I ignored him. He dumped the hellgrammite into a tobacco can and I could see that it held three or four more. He moved out into deep water and baited up. I went back to rolling my yellow nymph along on the bottom. I was coaxing it down into a pocket beside a big rock when Mac’s elated whoop rolled out. I knew before I looked around what had happened.

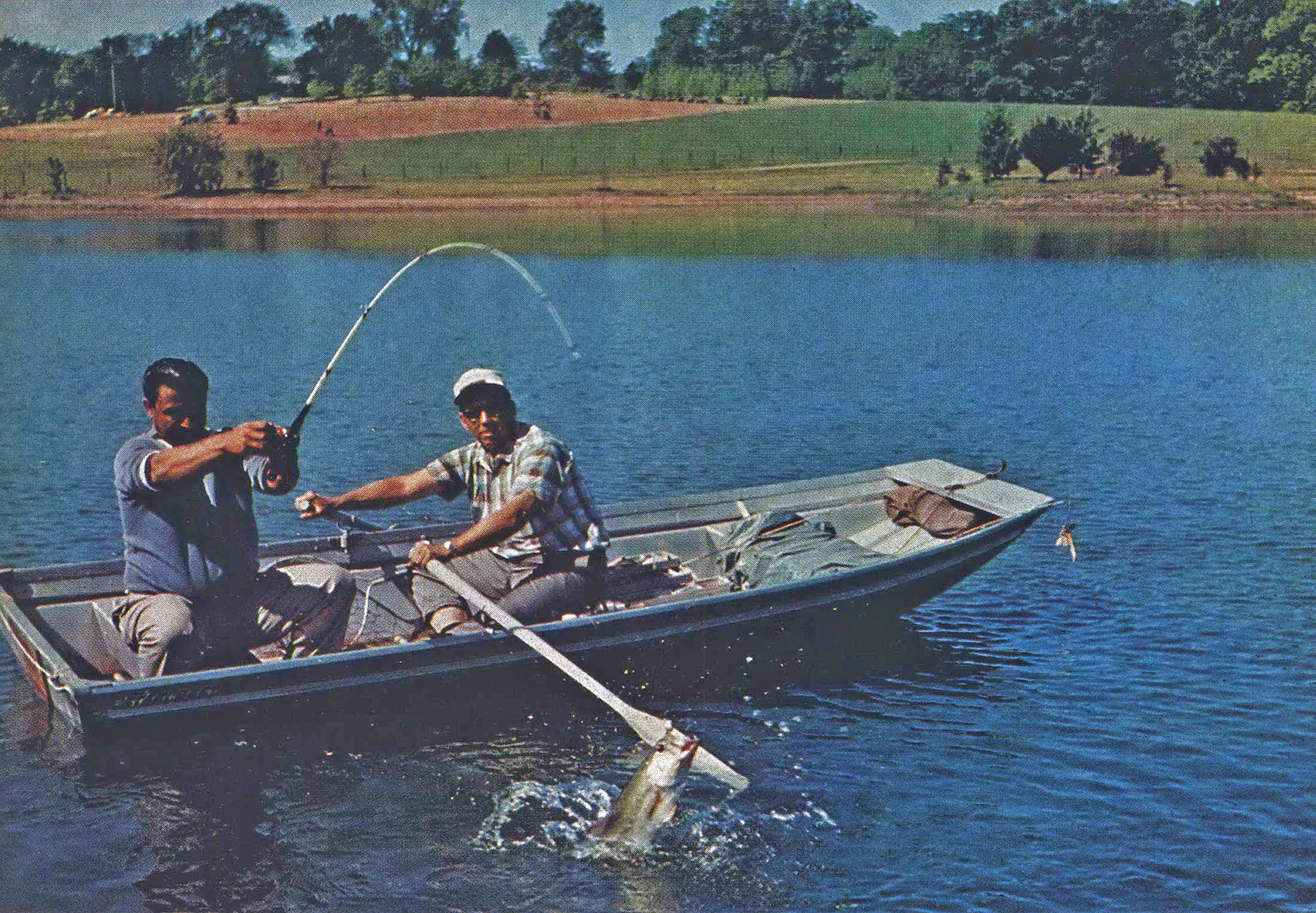

He was fast to a trout. And he was discovering one of the important things we had come down to the Smokies to learn-an eastern Tennessee rainbow is exactly like rainbows the world over. The fish made a short, fast run and came out of water in a skipping toe dance.

There seemed to be about a foot of him, and he was as full of action as if he had rockets in his tail. Mac uses a light trout rod and a leader that permits no rough stuff. The rain bow took him all over the creek. A couple of times he got under a ledge and I thought the jig was up. But Mac knows how to handle a situation of that kind.

It was a good lively scrap, with plenty of infighting, and the trout held out as long as any rainbow of that size can be expected to. When Mac finally led him within reach of the net I waded over for a closer look. He measured thirteen inches and was as handsome as any trout of his breed I had ever seen. I said as much.

“You want one of my grampuses?” Mac offered with a grin.

“No thanks. I’ll dig my own bait.”

I went over to a shoal place along the bank and started searching under stones. A little grampus scuttled out and I shut my teeth together and nailed him. Then I caught a bigger one. The sensation wasn’t as bad as I had expected. By the time I had six of them my long-standing aversion to hellgrammites had just about disappeared. Fish bait is fish bait, I reminded myself. I turned my back on Mac and waded upstream beyond the first bend. There was a deep hole up there that simply had to harbor a good rainbow.

He was there. I braced myself in the swift current thirty feet above the hole and let a big ugly grampus roll down along the bottom. The trout sucked him in like a kid with a lollipop, and the show was on.

My fish wasn’t as big as Mac’s, but he was lightning-on-wheels in that fast water and there was nothing wrong with his staying powers. He gave a great account of himself, and when I finally had him in the net I could have kissed him on both cheeks out of sheer gratitude. He had broken the jinx that had dogged me for three days. Now I’d catch fish!

Singing in the Rain

It worked out exactly that way, too. I took five rainbows with the six grampuses. The little one was swiped off the hook by a trout in his own class. When I went back around the bend to join Mac he had seven fish in his creel. Our best trout was just short of fifteen inches, our smallest nine. We were still admiring them when we heard, for the second time that day, a distant rumble of thunder and looked up to see black clouds again rolling in Cades Cove.

We tried to beat the storm to the car but we didn’t make it. There was no shelter in the laurel thickets, and two wetter fishermen never came off a stream than we were when we headed up the looping road that climbs out of the cove. But we weren’t beefing. We had accomplished what we had come to do, learned what we wanted to know. Best of all, for once we had won a knockout decision over a heavyweight fisherman’s jinx!

Read Next: The Best Trout Fly Rods

“I suppose it was just a case of feeding these confounded trout what they wanted,” Mac said thoughtfully. “All the same, the next time somebody puts a curse on me I’m going to look for grampuses!”

“Me, too,” I agreed heartily. “I don’t hate hellgrammites any more!”

Read the full article here