We Tracked a Cougar into a Box Canyon Maze. The Cliffs Almost Killed Us and Our Horses

This story, “Riding for a Fall,” appeared in the June 1954 issue of Outdoor Life.

It was dark. Except for a sliver of moon and a few stars flung across the sky, velvet black sealed us off in a small island of the canyon-gashed mountains of New Mexico.

George Hightower sat his saddle carelessly, arms resting over the pommel. He was only a few yards away, but the night made him only another blob in a world of shapeless blobs. “If you happen to ask,” he said quietly, “we are in a hell of a mess.”

I didn’t answer. Being in a hell of a mess was becoming routine for this mountain man and me tonight, and the worst was still ahead of us.

“There are parts of this country,” George continued, “that not even a lion could get through in the dark.”

The canyon that opened before us in an apparently bottomless chasm emphasized his words. There didn’t seem to be any way across or around it. I wondered if this was to be the spectacular end of our seven days in the Gila River wilderness. Not that I was particularly concerned. I was too tired and disappointed to care much whether we ever got out of this frigid, midnight land. But George hadn’t given up yet; he was still trying.

“We’ve come to the end of the trail here,” he said. “We’d better climb again.”

He pulled his horse around and clanked across the rough stones on the hillside, plowing through brushy clumps that all but raked me from the saddle. We crossed the rocky gut of a draw and turned uphill, around a slope so steep that J.T., my horse, had to balance like a tightrope walker to stay on his feet. I held on, while stones dislodged by George’s paint horse above me sliced past us through the darkness.

In all my years of scrambling up and down the uneven crust of the earth, I’d never made a hunting trip as rough as this. From daylight until dark each day, we covered 30 miles or more through a land as rugged as anything I’ve seen south of Alaska’s Talkeetna heights. We squeezed through crevices where I could literally touch the 1,000-foot walls on both sides by holding out my arms. With the thermometer ranging from zero before dawn to 30° above in the heat of the day, we inched our way through granite guts glazed with ice, and rode along rims where any misstep would send us hurtling into space. The regions which had been merely names on the map — Bear Canyon, Jordan, Sycamore, and Turkey Creek — were now uncomfortably real.

For seven days we’d been after an old male mountain lion, whose tracks George found two days before I came to the Gila. Ed Tucker, seated at the wheel of his mountain-geared truck, told me about him the afternoon we turned off the dirt road at Sapillo Creek and drove up a crooked canyon on a faint jeep trail. Following one series of canyons after another, we twisted upward for almost 30 miles to the continental divide, and then dropped off a series of mammoth ridges to the Gila River and the Heart Bar ranch, where George Hightower lives. Beyond the ranch, in the heart of the Gila National Forest, sprawled half a million acres of roadless, wild land, about as untamed as it was when Geronimo, the Apache chief, hid his warriors there.

“If you happen to ask,” he said quietly, “we are in a hell of a mess.”

This Gila wilderness fascinated me. Threaded only by a few trails to its more accessible spots, it has been dedicated unspoiled to American sportsmen. Deer and bear are abundant, and every canyon and mesa has its flocks of wild turkeys. Both trout and bass abound in the waters making up the three forks of the Gila River. The web of canyons branching off the main streams covers 1,000 square miles. The New Mexico Department of Fish and Game and the U. S. Forest Service plan to stock both elk and mountain sheep in areas here where they once thrived.

George Hightower is the lone guardian of this vast region. Protecting his game from poachers isn’t too difficult, because there’s no way to get into the country except through his front yard. So he has other jobs too, and one of them involves controlling such predators as mountain lions and coyotes.

All his life George has been a mountain man. For years he served with the Border Patrol, and gave up a fine promotion to a desk job to get back into the wilderness, where every track, upturned leaf, and broken twig tells him a story. He killed his first lion at the age of 10, when his coon dogs treed one of the big cats in a brushy arroyo. Since that time he has taken 103 lions. His closest call came when his dogs bayed a cub under a log and the mother jumped out of nowhere on his back. The dogs hit her at the same time and the fighting animals shredded his clothes before the lion left the scrap and treed in a near-by piñon. George caught the cub and raised it to maturity before he turned it over to a zoo.

The night I reached the Heart Bar ranch, Raymond Gibson, an old hunting partner of the Hightowers, from El Paso, introduced me to the pack of lion hounds. They are huge, rangy, well-developed dogs, bred from such strains as Walker, bluetick, and black and tan with a touch of bloodhound tossed in. They had been well trained, too. No trail but a lion’s would interest them.

For the first three days of my hunt with George and Ray, the weather favored the big cats. Temperatures rose into the 30’s and brought skiffs of snow that spread two inches of the white stuff over the mesas and in the canyons. I thought it might be good for tracking but George shook his head.

“It’ll melt on the south slopes out of the wind,” he explained, “and wash away the scent as quick as a spring rain.”

I’m sure the melting snow cost us one lion. On the fourth day of hard riding and harder climbing afoot, we found a track crossing a massive tongue of land from one unnamed canyon to another, high above the west rim of the river. The print was more than 24 hours old, but George put his dogs on it and followed them afoot into the jagged earth between the canyon top and river, leaving Ray and me to bring the horses around the rim.

For more than two hours Ray and I crouched on the broken rim of this gorge and listened to the dogs work the cold trail until suddenly the whole pack started a ringing chorus.

“They’ve jumped him!” Ray exclaimed.

I pawed my way around the ledge until I found a crack leading into the chasm. Despite my clawing at every hold, I slid down until my leather chaps were hot and the seat of my breeches almost smoked before I could regain my feet.

From where Ray and I had perched on the high plateau, the area the dogs were working looked almost flat. Instead, it was a jumble of points and careless ledges. I scrambled through it until I caught up with the pack on the last jagged brink that dropped off into the river. George discovered me panting behind him and raised his brows.

“Sounded like it was getting close,” I gasped.

He swore under his breath, then added, “They lost him in that mess of cliffs where the snow has melted. Ray and I caught an old tom there last spring, and I thought we had another one today for sure.”

He and Ray had treed the cat on a rock that stuck out over the river at a point where it was 300 yards to the water-straight down. If they shot the lion, there wasn’t any way to keep him from falling, and George was afraid a dog or two would jump on the dying cat and fall with him.

So George edged close and — just as Ray pulled the trigger — jumped and caught the big cat by its tail.

“If Ray had only winged him,” he said, “it wouldn’t have been like holding a kitten in my lap.”

Luckily, the bullet was fatal. The lion hit the ground with George holding on and four dogs piled on top of them. The sinewy mountain man dug in and pulled the lion and swarming dogs to safer ground.

While he was telling me about it, two of the dogs came back, but Spot, his silent tracker, and Bull, a persistent old hound with a wrinkled head and a voice like the hollow diapason on an organ, refused to quit the trail. So we stayed with them for two hours, circling, examining every crevice where the cougar could have gone off toward the river, even searching a couple of spire-flanked saddles where he could have crossed into Green Fly Canyon. The lion seemed to have vanished into thin air.

It was late afternoon when we gave up and crawled, sweat-soaked and exhausted, back to the rim where Ray waited with our mounts for the 15-mile ride to the ranch.

Ray returned to El Paso the next morning and George and I, still not satisfied, went back to the middle fork of the Gila, where we’d lost the lion’s trail. All day we cut for tracks in a pair of mammoth, unnamed canyons south of Green Fly, and looked at old lion markings at the base of trees and rocks. The only exciting moment of the day was the discovery of a small buck deer, so freshly killed it was still warm. But tracks said a pair of coyotes did it, not the cougar.

Delbert George, a cowboy and experienced lion hunter from the XSX ranch downriver, met us when we rode in that night. He had waited to tell us he’d run across the track of an old lion at the head of Woodland Park. The panther was padding through the high forest toward Brushy Mountain and Sycamore Canyon. Delbert was certain we could find him there the next day.

“It must have been the one we missed,” George grumbled.

Delbert said he’d bring along several of his and Jack Hooker’s best hounds and help us hunt out the wild upheaval of earth beyond Brushy. So we met him at a point six miles from the ranch at sunup that morning and started the two packs of dogs on a long ridge that ended in a ragged point overlooking the main flow of the Gila. On that very ridge our dogs struck lion scent. From their excited chorus, it was hot. They worked both sides of the ridge for an hour, then took off cross-country into a land that had but two obvious dimensions — up and down.

All day we followed the dogs, until my horse was wrapped in lather and I staggered like a drunk every time I dismounted. George and Delbert recognized four distinct tracks — a lion, lioness, and two cubs. The family had crossed two canyons, gone off the steep point of a ridge, and somewhere there had turned back across the mountain into the canyons again. The dogs raced to this point and then milled around in confusion until we ran out of daylight.

With some difficulty we called them off the trail, and started climbing out while we still had light enough to see. First we headed toward a massive landmark known as Steamboat Rock, then over the top of Brushy Mountain. Just as the last light faded, Delbert veered off toward his ranch, While George and I turned down a long ridge toward one of the few crossings that would put us through the tremendous canyon of Little Creek and on the way home.

In the first hours of darkness when all the ridges so closely resembled one another, we pitched off on the wrong slope and ended up in the maze of canyons flanking Little Turkey Creek. It was here that the sliver of moon went down, leaving us walled in darkness. That was when we turned back up the hillside to find the ridge we had missed.

When I caught up with him again, George was off his horse, kneeling on the ground, looking for sign even in the darkness.

“I’m sure,” he said, “this is the slope that will put us through Little Creek.”

“Why don’t we build a fire,” I suggested timorously, “and wait for daylight?”

“When there’s hot coffee and a warm bed over yonder a few miles?” George demanded.

“O.K.,” I sighed. “Shove off.”

I wouldn’t have been so nonchalant if I’d had an inkling of the wild midnight ride we were embarking on. In the gloom my horse, J.T., seemed suddenly to acquire a strange affinity for trees. On that entire mountain slope I don’t believe he missed a thicket, unless I saw it in time to pull him around. When he caught me off guard, all I could do was lie down in the saddle and cross my arms over my head to keep an eye from being gouged out. The brush literally riddled the back of my heavy hunting coat.

Down and on down we went, across rugged and rocky terrain, feeling our way at last to the rim of the creek. Even in the blackness, we could see the silhouette of a wall 300 yards high on the far side, and we judged the rim we stood on dropped 100 feet straight down to the water. We were cut off.

I stepped out of the saddle to hold the horses while George kept on afoot to find some place where we could get our horses down into the box canyon. A few yards from where he left me, he stepped on a rock that was coated with frozen snow, lost his balance, and shot toward the brink of the canyon. He saved himself only by throwing his body toward a tree on the brink and hooking one arm around the trunk. The rough bark peeled his hand and the side of his face and he came back with blood streaming down his cheek and freezing on his collar.

Moving more cautiously, he went in the other direction and in 30 or 40 minutes returned to where I stood shivering with cold.

“I found a way down,” he said, “but it isn’t paved by a damn sight.”

Feeling for each step in the blackness to keep from stumbling over the rim, we worked along the bluff to where a rocky shelf slanted down to the creek at an abrupt 60° angle. Then, leading our horses, we slid down it to the bottom of the canyon.

The creek, about 20 feet wide between its sheer walls, was sealed under two inches of ice. George smashed the ice along the edge with a heavy stone, and we fell on our faces, elbowing the dogs and horses aside to drink with them in the broken hole. It was the first water any of us had tasted since daylight.

We had thought that, once in the creek, we could go either up or down the canyon until we found a trail leading home. Now we found our troubles had only begun. The horses couldn’t climb back up the chute where we slid down to the creek. It was practically suicide to try to stand or walk on the ice-coated ledges that bordered the stream, and even the horses had difficulty in navigating the uneven, slippery creek bed. They broke through the ice in places where the water came almost to their bellies.

We went stumbling and blundering upstream for almost half a mile before our way was blocked by a frozen waterfall. We couldn’t have climbed it with tree-climbing spikes. Below the fall, the north cliff was split by a narrow seam that turned almost straight up and disappeared into the darkness of the rocks above.

“If you’ll stay with the horses,” I suggested, “I’ll crawl up there and see if that chimney comes out somewhere.”

“If it doesn’t,” George replied, “I’ll be rimmed in for the first time in my life, and I’ve followed cat tracks through every wilderness in New Mexico.”

The rocky slant was too steep to stand on. Thankful that I wore heavy leather gloves, I crawled up it on my hands and knees for more than 200 yards to a narrow, grassy bench hanging on the wall of the canyon. From this bench to the next grassy slope that led up into the timber was a jump-up of some five feet that didn’t appear too difficult for a horse. I pulled my body over this and labored for another 200 yards up a hillside as steep as the roof on an English house before returning to where George waited in the creek with the horses and dogs.

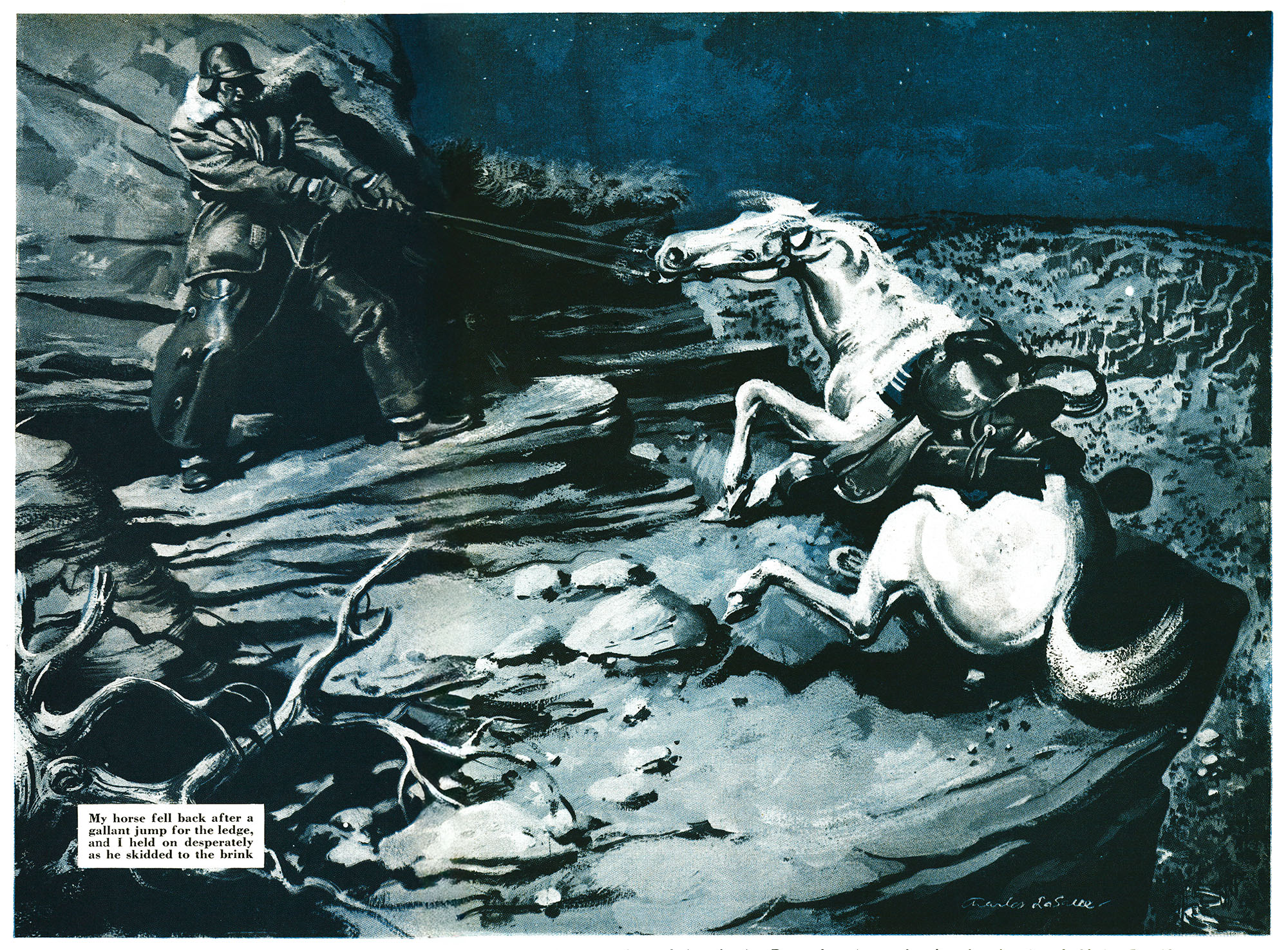

With his hoofs beating a tattoo on the stone, he lost his balance and fell backward onto the sloping, 10-foot shelf that dangled over 600 feet of space.

We could try to climb out — or spend all night in the frozen canyon. So I led J.T. up first. With his steel shoes slipping and knocking sparks out of the rock like an emery wheel, J.T. and I climbed like spiders until we reached the bench. Now if we could scale the last little rim to the grassy roof of the canyon we’d be on dirt again.

I crawled up first. Behind me, J.T. made a gallant jump and almost made it. With his hoofs beating a tattoo on the stone, he lost his balance and fell backward onto the sloping, 10-foot shelf that dangled over 600 feet of space. I was sure we’d both go over, for I was holding the reins. But I dug in desperately, and in some truly miraculous manner J.T. managed to regain his balance right on the edge. He stood trembling while I hitched my way down to him. I patted his shoulder and neck and talked to him until he stopped shaking. Then I led him a couple of paces away from the ledge, which was as far as we could go, and left him standing there while I slid back to the creek to help George with his horse.

The paint was stubborn and George was as mad as I ever saw him. His horse, in attempting to jump the steep bottom rock into the seam, had slid back into the creek, and refused to make another start.

I took the paint’s bridle reins, plastered myself against the rock above and pulled, while the mountain man worked him over with a driftwood pole. The paint reared on his hind legs, jerking me off the rock wall into the creek. So George got in front to pull, while I splashed around in broken ice and knee-deep water and poled the horse on the rump. No go. After 40 minutes, all three of us were near exhaustion.

“If I can find enough driftwood,” I suggested, “I’ll build a fire and spend the night here. You and J.T. and the dogs can go on home. Come morning, I’ll find a way to get the paint out.”

“I’ve got a better idea,” George said. “I’ve never left a horse anywhere unless he was dead, but I’m going to unsaddle this mule-head and leave him here until tomorrow.”

We peeled off the saddle and packed it into a rocky niche of the wall, where the paint wouldn’t knock it off into the creek if he decided to follow us on his own, and left him standing knee-deep in the icy water. He nickered like a forlorn and frightened colt as we left, and I was tempted to turn back and spend the rest of the night with him.

J.T. was where I’d left him. I don’t believe he’d moved a muscle. From the sounds he made, he was glad to have company.

“You’ll have to get him over that rock wall,” I told George. “If I caused him to slip off into the canyon, I’d probably jump in after him.”

George inched up the rock with the reins in his hand, and when he pulled I rapped the horse across the rump. J.T. made a tremendous leap, seeming to hang in space above me for a moment, balancing precariously on the very rim of the ledge. Then he gave another heave and got four feet on solid earth. I heard George’s breath of relief in the darkness above me. The dogs scrambled up with no trouble.

From the canyon rim to the crest of the mountain, angling up 45° above us, was about three quarters of a mile and we climbed it afoot, both out of respect for a faithful and gallant horse and to keep warm. I was awkward and stiff and rattled with every step. My chaps and pants legs from the knees down were cased in ice and stiff as stove pipes.

Out on top of the ridge, the starlight showed we were still surrounded by canyons as deep as the one we’d just escaped. Back and forth we went, trying to find a way out of this labyrinth of yawning earth. Twice we walked to the very edge of points that pitched off into the night and had to turn back toward the crest again.

Then George hit a zigzag course leading off to the north through brush and bushy trees, and an hour later we found a low gap between the rims of two canyons. It took us to a long, flat mountain sloping toward the ranch.

It was 3 o’clock when we unsaddled J.T. and tried to feed the dogs, but they collapsed in the hay under the shed, too tired to eat.

Read Next: That Time Our Editor-in-Chief Interviewed Teddy Roosevelt After His Mountain Lion Hunt

That ended my hunt. My time had run out. A letter from George tells me now what I missed: “The paint was standing right where we left him when I went back next day,” George writes, “and it took me till dark to get him home by another route, even with daylight to pick my trail.”

But what I regret missing is this: George treed our cliff-dwelling lion the Sunday after I left. The lion laid up in the bluffs, and Spot (the dog that seldom barked) got under the rim and jumped him. The hounds treed the cat three times before George got in a shot, and then he dropped him just as he was ready to leave the tree again. He was a nice male with a prime hide.

“Oh, yes,” George adds. “Come back and look at that canyon we crossed in the dark. See it in the daylight and you’ll agree there’s more to hunting lions than just finding them.”

George can say that again!

Read the full article here