They Tell You to Play Dead When a Brown Bear Attacks. I Found Out If It Really Works

This story, “Nightmare Hunt,” appeared in the Nov. 1985 issue of Outdoor Life.

My hunting buddy, Darrel Rosin, chided me as we pushed aside the high brush on the narrow path leading back to the cabin.

“Thought you told me these bears up here go after moose nose like kids after ice cream,” Darrel kidded. “Here we’ve been on this moose hunt for two weeks and nary the sign of a bear. Just doesn’t stack up.”

Whether we had seen them or not, we were in bear country. It was the tag end of the moose season in southern Alaska, 50 miles south of Soldotna, 200 miles south of Anchorage.

I was getting anxious about our lack of success as the end of our trip drew near. Finally, my dad, Wes, and my brother, Wayne, managed to get their moose on the same day, but neither Darrel nor I scored.

On one of the last days of our moose hunt, Darrel and I started off through the high willows that surrounded our camp. We had our minds set on adding two more moose carcasses to those already hanging in the tree near the cabin.

Darrel figured that he’d get his from a platform we had built 20 feet up in a tall spruce tree four years earlier. It was a terrific lookout, commanding a splendid view across the thick brush, spruce stands, and tundra bogs.

Darrel let it be known that he was going to get his moose if it took him all day — and it nearly did. At 5 p.m., I heard a shot from Darrel’s Ruger 77.

“Got him!” I heard Darrel yell. “At 100 yards.” It was a little after 7 p.m. when we finished dressing his kill and were starting back to the cabin to stow our meat ax, saw, and rope.

The spruce shadows were, for me, depressingly long. Darrel had gotten his moose, but I was still empty-handed. I was thinking of using up the last half-hour or so of twilight to locate a bull that I knew had been with the rest of the bulls we’d taken.

If I couldn’t get him tonight, I’d get him at first light tomorrow. Only one day of the season remained.

I stepped just a couple of feet away from Darrel and stopped, listening. Though I couldn’t explain it, the silence cloaking the wilderness seemed somehow different. But then, the whole two weeks of September 1985 had been different.

I checked my compass and shoved it in a rear pocket of my hunting pants. I thought to myself that dad and Wayne were just about finishing their spaghetti dinner a couple of miles down the road at the cabin of our friend, Lou Clarke. I also was thinking how spooky everything seemed out here in the deep twilight and vast wilderness. It was then that I heard a faint rustling in the brush 100 feet or so away.

“It’s your moose,” Darrel called out. “Go get him, buster.”

That rustling was almost a summons. That was my moose. I had to get him now. Somehow I wanted to be alone when I got him.

“Go on ahead,” I told Darrel. “I’m going back to meet him. What’ll you bet he’s a 70-incher?”

“Shout ‘whoopee’ when you get him.” Darrel hollered, waving me off and continuing toward the cabin.

Now the adrenaline was flowing through me — but good. I was as anxious and fired up as I had been on previous hunting trips when I got my eight moose. Each year, it seemed, those moments before the kill got more and more tense and anxious. I cut back the way we had come, angling northward in the direction of the intermittent rustling. Everything seemed fine. I kept low, crouching, on the lookout for anything that moved, testing each step for noise before I shifted my entire weight, and listening for sounds up ahead.

Realizing that the bull might be closer to me than I’d figured earlier, I geared up mentally for sudden action at close range. Another deep and eerie silence settled, and quieting my anxious thoughts wasn’t easy. A spine-tingling sensation swept over me — the feeling that whatever I had been watching for in the thick brush up ahead had been, or maybe was, watching me. I didn’t dare move fast.

I was waiting for the rustling sound, picturing a hefty bull, a moose with the longed for 70-inch rack, a critter far bigger than dad’s or Wayne’s or all the eight moose I had taken in other years.

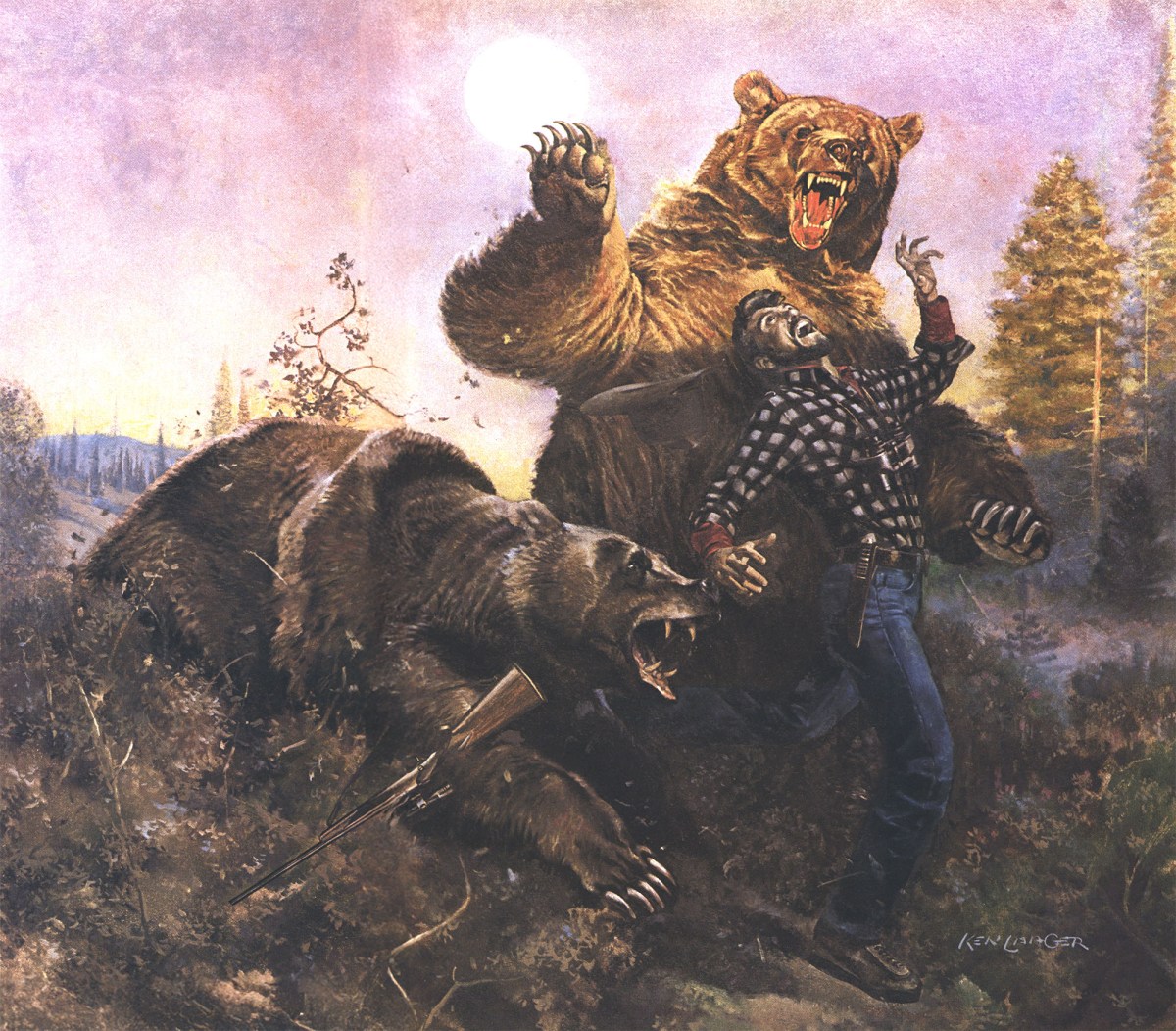

Suddenly, in a sound that came to me like the crack of summer lightning, under brush snapped a couple of hundred feet away. I stared in the direction of the noise and heard another branch crack, only this time it was much louder. Slowly, just 40 feet ahead, I saw the brush beginning to part. My breath stopped in my throat and I gasped as the leaves split apart like a green stage curtain revealing two of the fastest, biggest brown bears I’d ever seen, charging right at me.

“My God!” I heard myself stammer.

In a flash, I took stock. I had a few seconds — no more — to shoot at the half-growling, half-grunting, charging beasts. One was barreling half a length in front of the other. I yelled, but they kept right on coming — their ugly brown faces glistening in the twilight, the rolling fur on their backs undulating like waves on the ocean.

Their huge jaws were open, revealing rows of razor-sharp teeth plainly visible at 30 feet. Their big heads reared up when they saw me, their tongues hanging out. They neither hesitated, nor slowed down. Now there was no time for fear or paralysis. Each bear must have been several feet tall, weighing 400 pounds or more. In that split second, they looked to me like monsters from outer space.

It is amazing how much agility comes with reflex in a life-or-death situation. I whirled to the right, hoping that my .338-caliber Ruger 77 would do the job.

I shot from the waist. The crack of my rifle seemed to reverberate for miles. I looked ahead. “My God,” I thought, “nothing’s changed.” The bears were glaring, still charging toward me. I’m a crack shot but, this time, when it really mattered, I missed. Besides, when two are coming, which one do you aim for? The bullet hit a tree.

Now, plainly visible were the ugly, yellow, razor spikes of teeth protruding from drooling jaws. I froze. Time seemed to stop, and I remember glancing at the beasts’ claws for just a second. Before I could chamber another round, they’d be on me. I spun on my heels; now my back was to them and I was braced for their first blows. I dropped my rifle and threw my hands over my face, shielding my eyes. As I did this, the bears lunged. I felt a staggering blow against my back and then a force, like a team of line backers, struck my shoulders, knocking me down. Sharp sticks cut my lips and weeds jammed in my mouth. My nose and forehead were wedged flat against the forest moss. Then, a ton of weight, like the wheels of a car, pinned down my back. I could hear strange, thick, guttural animal sounds and the sound of spasmodic breathing.

What I decided then was wrong — I know it now, but I wasn’t thinking clearly at the time. I had been thrashing my arms and legs, but it suddenly occurred to me that my struggle was futile. “Why fight?” I asked myself. “You’re dead already. Why resist?” At that moment, one of the bears started chewing my ear after knocking my cowboy hat off.

Something in me advised: “Play dead. Bears are supposed to get disinterested and leave. But you’ve got to lie perfectly still.” Still? “Dear God, how?” a voice within me screamed. I jammed my thumbs down into the earth as the first of countless agonizing needles began piercing my buttocks and up and down my spine. Now, the slashing at tack moved higher.

Horror swept me as I felt pressure, like a foot, near my ear. Then the real agony — I felt one of the beasts yanking my head up to get a better grip on my neck. Stifling a scream, I ground my mouth into the earth.

The grating sound intensified. Instead of letting up, the bears began getting more ferocious. My entire body was being shoved and shaken with tremendous animal power. My knees were being stomped and ground down into the brush. One of the beasts was working on my back, the other on my skull. Then, they traded places. The sequence of events is hard to sort out, though. My mental pictures of the agony are mercifully blurred.

The most horrible sensations came when they began gnawing at my head. I had a mental image of one of the bears clamping its open jaw around the entire top of my head, attempting to crush in the bones, but not quite succeeding. I heard the animals panting in my cars. I figured that I was in the throes of death. Death from bleeding. Death from shock.

I fought to keep from moving or twitching. Something in me seemed to be ordering me to lie still, motionless, but my body rebelled and my left leg twitched sharply. Every time there was movement, it was followed by a burst of more needles of shooting pain.

They chewed on my head and back for what seemed hours, or days. Then they stopped abruptly to rest. I sprawled absolutely motionless and silent, my heart thumping wildly. I could feel my pulse pounding in my wrists and temples.

“Lay still,” I warned myself. “Don’t move. You’ve lost a lot of blood. Try to run and they’ll flatten you and finish the job. If you as much as twitch, you’re done for.”

I stiffened my knees to hold them firm, but the effort brought movement that instantly caught the bears’ attention and brought both of them roaring to a standing position. Then they settled back and I could see them several yards away, their piglike eyes glaring at me.

Miraculously, I was still alive — but for how long? How many arteries and blood vessels can rupture before you bleed to death? How many slashes can you take and still remain perfectly motionless?

Somehow, it comforted me to think about what I had been told all my life: After they kill, bears will refuse to immediately devour a human meal. They have been known to gulp down a moose kill, but you can count on them moving off without completely devouring the remains of a man. Sometimes, they return to cover the meat with leaves and twigs, but they go away for days until decomposition progresses to a certain stage. Bears have been known to relish rancid meat. But a fresh kill? They usually walk off as if it were poison.

I’ll never forget the wave of relief and thankfulness that swept over me when the creatures were no longer on my back, jabbing and pulling.

“Are they gone?” a voice inside me asked. “Look and see.”

Saliva clogged my mouth and throat. Slowly, I turned my head to the left. My face was caked with blood-soaked dirt, so I wiped my eyes and tried to look into the distance. That was all those waiting bears needed. Roaring, they were back at me, pouncing with new ferocity. One of them clamped its fangs on my shoulder, sending sharp teeth deep into muscle as pain zig zagged down my side, down my leg, to my toes. Now they began in earnest to rip the flesh at the back of my skull.

Slowly, I turned my head to the left. My face was caked with blood-soaked dirt, so I wiped my eyes and tried to look into the distance. That was all those waiting bears needed.

Despite the intense pain, the only thing on my mind was my children.

“Dear God,” I begged. “Let me live. I want to see Max and Melinda again. God, let me live.”

Things seemed to go blank for a moment and the scene wavered. Then, as if I were detached from the horror now enveloping me, a part of me began lecturing to the other part. I heard myself say, “Go limp … repeat over and over: I am still, still as death. I will let them chew. I will not move … I will play dead … play dead … let it happen … let them have me …

“I can’t,” a part of me resisted.

“Yes, you can. Repeat: I will let them chew. I will not move. I will play dead.” My inner voice seemed to be repeating the admonitions over and over.

I do not know how many minutes or seconds this eerie confab went on. I had long since lost track of how much time had passed. Tremors of pain were cutting into my chest now. A new and terrible fear seized me as the bears moved from my back to other parts of my body and alongside my lungs.

Then, in one moment, all of life seemed to ebb and stand still. Gone was the slurping, pulling, grunting, crunching, licking. Silence. Dead silence. “How,” I wondered, “can something so huge move off so fast and so silently?”

But I knew they were nearby, sitting only yards away, their eyes watching for the slightest movement, their cars tensed for the slightest sound from my body. I forced myself not to look, not to raise my head, not to move so much as a finger or an eye lash. Now, all was deep, agonizing silence. Nothing moved. From my limbs, neck, and face, blood seeped silently into the dirt. My body seemed frozen, gl1ed down, a part of the earth. Motionless, I listened. Now there was no rustling, no footsteps, no dry twigs breaking.

“Dear God,” I thought, “Do I dare raise my head? Will they come at me again?”

I kept my eyes closed tight and a kind of peace filtered through the pain. I saw the little church that I attended in Soldotna. I saw my dad and mom. I saw my sister, JoAnn, and my brothers. I was with them and suddenly, somehow, I got the courage to lift my head just a little bit so I could look around.

The bears were gone. But how far? Were they lurking just behind that clump of spruce trees, ready to charge again? I had no idea where the bears were, but I told myself that, if they came back, I’d let them finish me off and end my suffering. I didn’t want any more of that awful pain. But they weren’t around, and somehow I had to find the strength to get away.

“Try getting up,” I told myself. “See if you can stand without falling.” Was I brain damaged in the attack? I had to be able to think. If a lot of my brain was gone, would I be rational? Could I trust my thinking? Fighting back the pain, I somehow was able to get on my feet. I realized then that my legs hadn’t been broken. I lifted my hands to feel my head. My hand slid under my scalp as under a hat. I took my binoculars off over my head, unbuttoned my wool shirt with one hand, and slipped down my suspenders to strip off my shirt. There was no way I could let go of my head and re move my shirt without the loosened skin sliding out of place.

“I’ve got to get out of here fast.” I kept thinking, “But which way?” New blood poured down my cheeks, soaking my pants and shirt.

Despite all this, I felt no revulsion, just an aching hope that somehow I might get my shirt tied around my head to hold everything in place until I could get help. I could see partially, but every movement I made seemed to increase the bleeding and to bring on greater weakness.

“Dear Lord,” I prayed, “All the trees look the same. Show me which way to go. Help me to choose the right direction.”

Maybe, I thought, the bears are still lurking around.

“Help me,” I muttered aloud. “Help me.” Then I yelled, ‘”Darrel! Darrel! Help.”

I started to run. To this day I don’t know how, but I pushed the tall grass aside, stumbling, screaming. “Darrel! Help!”

Darrel heard my yelling. He cut back into the woods in the direction of my voice and then stopped dead in his tracks.

“Dear God!” he said as he saw me. “Oh, my God!”

I thought he was going to faint. but he helped me back to the cabin. Dad and Wayne were there when we arrived.

Someone gave me a mirror. I couldn’t believe that the awfully mangled creature I saw was me. The entire back of mv head, ear to ear, had been opened and lifted. The scalp was falling to the front like a slipped wig. A piece of scalp was missing. Punctures in my shoulder were so deep that I thought my lungs might be pierced. My back and legs were covered with gashes and bites. The bears’ teeth had punctured through more than three inches of buttocks flesh. My head had been chewed badly. Sticks, grass, dirt, and bear saliva were in the wounds. My favorite watch, the one I liked because it was thin and easy on the hunt, was crunched through the dial. It had stopped at exactly 7:33 p.m.

Working swiftly, Darrel made a tourniquet out of a towel and tightened it around my head. Dad, meanwhile, cleaned the blood from my face and body.

The guys flung a mattress into the trailer and I climbed in. The trailer was hooked onto our four-wheeler. By now, the pain was beginning to break through my consciousness as the protecting shock wore away.

Wayne was driving, and he frantically spun the wheels in his haste to get us out of the cabin and through the woods to our pickup truck parked six miles away. Once we got to the truck, we would drive 60 miles to Soldotna, where there would be a doc tor and a plane to take me to Providence Hospital in Anchorage, 200 miles away.

The white bath towel that the guys had in one of my buttocks was so great that I shifted my body in the trailer. It was too much effort to reach into my wool pants pocket to see what was jabbing me when ever we hit a bump. (I later found out that it was a chewing tobacco can.)

Conversation was sparse as we drove to the pickup truck. Darrel seemed to be feeling guilty about having not responded when he heard my shout and the shot I fired. But, at the time, Darrel thought that I had gotten my moose and was yelling “whoopee.”

“I was so happy for you,” he said. “I threw my hat in the air and hollered, ‘Yiiieee! Another moose bit the dust.’ If only I had known.”

Read Next: I’ve Killed Dozens of Bears. Here’s What Actually Makes a Great Bear Gun

What none of us knew was that more surprises were still in store. We got to the pickup only to find that we had to change a flat tire. Our troubles continued at the airline counter in Soldotna. There were no planes in the airport, so one was ordered to be flown out of Anchorage.

I arrived in the emergency room of Providence Hospital at 3 a.m. My physician, Dr. Jim Scully of Anchorage, spent five hours applying 200 stitches and flushing and picking pine needles from my skull.

Rollin Braden spent eight days in the hospital, four of them in intensive care. He survived the ordeal in record time and without disfigurement. On September 25, l985, he celebrated his 31st birthday. —The Editors.

Read the full article here