These Photos and Videos Reveal Why Maryland’s Blue Catfish Must Be Killed

Jay Fleming knows blue catfish eat just about anything. But it wasn’t until recently, when he visited a fish processing plant in Maryland and started slicing into their bellies, that he fully realized the volume and variety of their appetites.

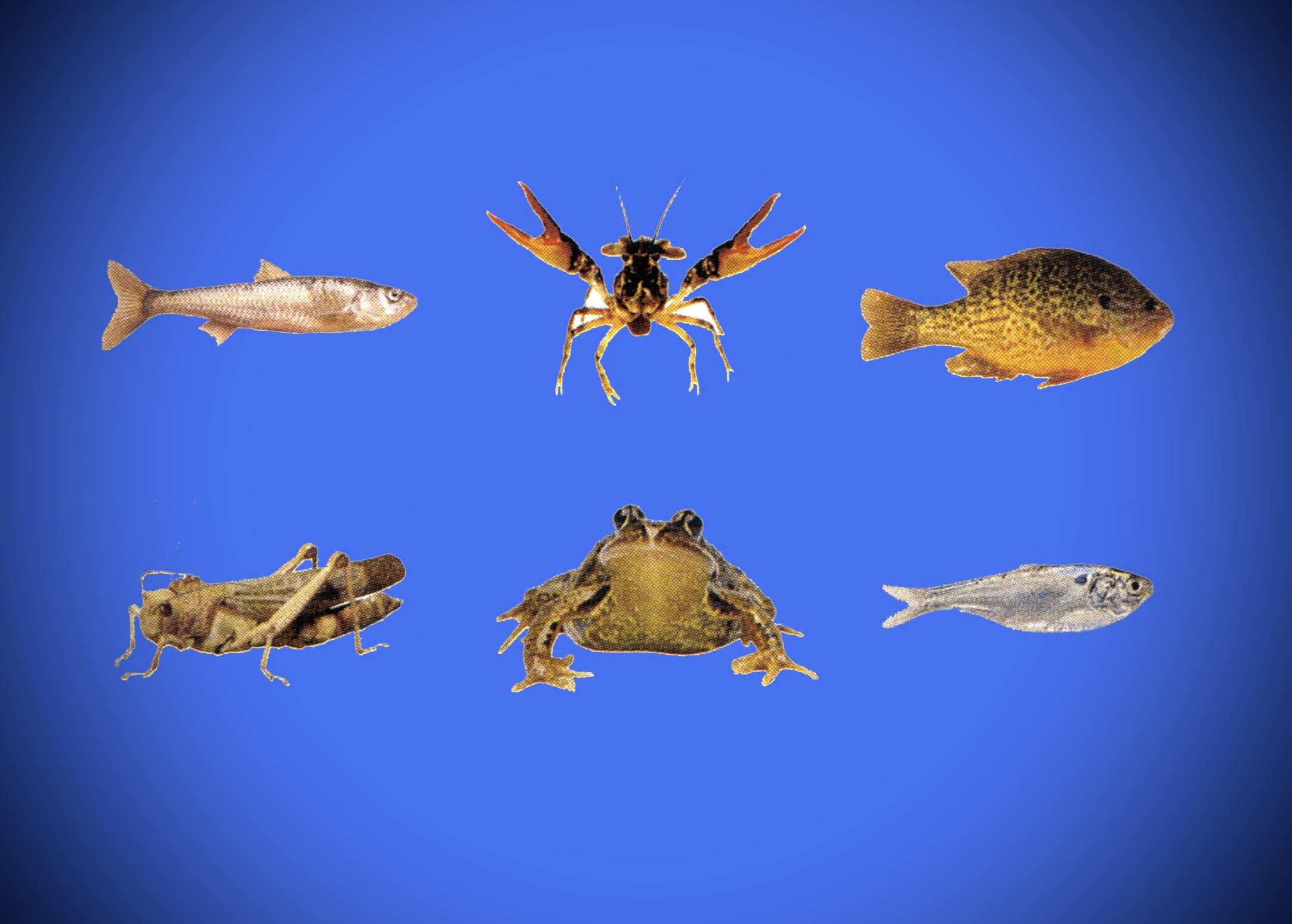

“They are eating shellfish, they’re eating clams, they’re eating crabs crawling on the bottom, they’re eating fish like perch, they’re eating fish at the top of the water column,” Fleming tells Outdoor Life. “ They’re very opportunistic feeders and they’ve really found an abundant food source in these rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. And their populations have blown up — big time.”

Fleming is a 37-year-old professional photographer from Annapolis who has been documenting the growing catfish problem in his beloved homewaters. Blue catfish — native to the Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Rio Grande river basins — were introduced to Virginia by the state game agency in 1974 and stocked for a decade. By the time fisheries managers realized they had unleashed a voracious monster that would outcompete native fish and could survive in the brackish water of the bay, it was too late. Now biologists and other conservationists are warning of an invasive critter crisis that threatens everything from blue crab to striped bass.

Virginia, meanwhile, still regulates blue catfish as a trophy species, in part to appease the region’s diehard catfishermen. These opposing interests — the health of the native ecosystem and the fun of catching giant blue cats — makes it difficult to manage catfish through recreational angling alone. The best chance for fighting catfish, say Fleming, lies in commercializing them.

Commercial Fishing for Catfish

Fleming knows a thing or two about the challenges of managing nonnative fish. For two years he worked for the National Park Service, operating a gill-net boat to remove invasive lake trout in Yellowstone. These days, he spends about 250 days a year on the water of Chesapeake Bay. Often, it’s running trot lines for blue catfish. He bought 1,200 feet of long lines off a commercial fisherman, and now he runs about 100 hooks per line, all baited with cut gizzard shad.

As part of his public-awareness crusade, Fleming takes everyone from high-school students to high-end chefs fishing for cats.

“People have this connotation that catfish are muddy bottom feeders. I think that comes from eating farm-raised catfish that live in ponds and are fed pellets. But this is a wild fish that’s eating menhaden, perch, crabs — they have a good diet,” says Fleming, who notes that blue catfish caught in the Chesapeake Bay watershed have delicious, mild white fillets. “By encouraging the market, that’s one way we can try to make a dent in the population.”

Research from 2011 shows that blue catfish made up as much as 75 percent of the fish biomass in the tidal James and Rappahannock rivers. That astronomical figure has likely increased in the decade since, as catfish are now in every major tributary of the Chesapeake Bay. (MDNR has some great interactive maps that show the expansion of the blue catfish range over time.) Fleming says the way to combat a full blue-cat takeover is by leveraging them as a resource.

“This is one of those rare opportunities where economics and the environment can work together. So by getting these fish out of the water and encouraging a sport fishery for them, which pumps money into the economy, and a commercial fishery, which employs watermen, it employs fish houses for cutting, and it brings money into restaurants. That’s a win-win.”

It’s also an opportunity for frustrated commercial fishermen to pivot. Blue cats target important forage fish like alewives and blueback herring, and they compete with sportfish for the same prey. Tissue sampling shows they eat striped bass eggs, too.

“Striped bass are the bread and butter for a lot of people here, and fisheries like striped bass are at risk because of these blue catfish,” says Fleming. “Commercial fishermen are used to getting regulated every step of the way. This is one of the few fisheries that’s pretty much unregulated.”

Commercial licenses for blue catfish are just $15 in Maryland, with no limits or size restrictions. And indeed, harvest numbers are growing year over year. In the Potomac River and Maryland waters, commercial blue catfish harvest jumped from 609,525 pounds in 2013 to 4.2 million pounds in 2023, an increase of more than 500 percent.

That’s a good start, but commercial outfits and sport anglers still have a lot more fishing to do. To keep the blue catfish population stable, Dr. Noah Bressman told the Teddy Roosevelt Conservation Partnership last year, commercial and sport fishermen need to remove between 15 and 30 million pounds of blue cats from the Chesapeake Bay each year. Bressman, an assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Salisbury University, says actually reducing the population would require a much higher harvest.

Trophy Catters vs. the World

Fleming never expects us to eradicate blue catfish in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. From spotted lanternflies in the Northeast to burmese pythons in the Everglades, controlling invasive species is usually a matter of management, not elimination. One of the main obstacles, now, are anglers themselves.

“Different groups of different fishermen have their own special interests. Among the striped bass crowd, they agree blue catfish are a problem,” says Fleming. “The striped bass fishermen are pretty supportive of getting as many catfish out of the water as possible. But then we’ve got a whole crowd of people, mostly on the Potomac and in Virginia — they’re trophy blue catfish people. And they’re pretty adamant about blue catfish being regulated as a trophy fishery. In Maryland, it’s wide open. You can kill whatever you catch. Virginia is still regulating it as a trophy fishery, which is kinda crazy.”

Fishermen in Virginia do have liberal daily limits of up to 20 fish or no limits at all, depending where you fish, but they usually can only keep one blue cat longer than 32 inches. In other words, Virginia requires big catfish to be released instead of killed and removed from the water. This is something catfish record-chasers support — and that troubles native-fish advocates.

“Who would’ve thought that something like this could be political? But it can,” says Fleming, who serves on Maryland’s Invasive Catfish Advisory Committee. The group also includes some “trophy catters,” as he calls them. “So there’s a constant push and pull between the different stake holders, and that’s only going to slow progress.”

According to Maryland fisheries biologists, those big trophy cats can be especially problematic.

“Once they reach a decent size, mortality drops off,” even for catfish far smaller than record sizes, MDNR’s invasive fishes program manager Branson Williams said last year. “They don’t have predators to worry about.”

Other sportfishermen are often frustrated by the blue cats, which crowd out their target species.

“They eat almost any lure you can think to throw,” says Derek Horner, OL’s social editor and a former collegiate bass fisherman who has fished all over the East Coast. “When you find the blue cats, the bass will vacate an area. Let’s say I fished on a Friday and caught a ton of largemouth on a flat, but then I show up Saturday and catch a few blue cats. The largemouth are outta there.”

Read Next: The Master Catfish Trotliners of the White River

Fortunately, Fleming points out, catching blue catfish isn’t just a good idea for conservation — it’s fun. Blue cats were brought to Virginia as a sport fishing opportunity, after all, and those opportunities abound.

”The catfish — they’re not a bad fish,” says Fleming. “They’re just in the wrong place. And they have a value.”

You can follow Fleming’s photography, fishing, and conservation work on Instagram and Facebook.

Read the full article here