The World-Record Whitetail Disappeared for 64 Years. It Was Rediscovered at a Rummage Sale

This story, “The All-Time No. 1 Whitetail,” appeared in the November 1979 issue of Outdoor Life. The Jordan buck remains the No. 1 largest typical ever taken by a hunter in the U.S., and the second largest in the world, after the Hansen buck. The Jordan buck is now owned by Bass Pro Shops. This story is based on the author’s interviews with Jim Jordan shortly before Jordan’s death, Jordan’s written record of the hunt, and talks with Jordan’s widow, Lena, who was still living near Hinckley, Minnesota, at the original time of publication.

Jim Jordan stared at the fresh deer tracks in the snow. Three, maybe four deer had recently shuffled by, he figured. But one set of hoof marks caught his eye. The snow molded hoofs were huge; the toes splayed outward like the legs of an overloaded chair.

Jordan cradled a .25/20-caliber Winchester in his arms and took a deep breath of cold morning air. If the tracks were any indication, he had crossed paths with a huge whitetail buck. Jordan peered at the tracks again. He had never seen such massive hoofs. He knew he had to follow the inviting track. That decision launched him on a bizarre deer hunt that really lasted for 64 years.

The tracks Jim Jordan followed on a November morning in 1914 were made by the world-record whitetail buck. But for more than six decades, a series of strange twists of fate kept Jordan from being recognized as the man who shot the great buck.

The current edition of North American Big Game, the record book, states that the name of the hunter who took the world-record typical whitetail is unknown. The record book also states that the location was Sandstone, Minnesota, which has turned out to be a mistake.

For more than 60 years, about the only thing known about the No. 1 set of antlers was that they were discovered at a rummage sale in Sandstone. When Jordan heard of that discovery, he knew that the record really be longed in his name. He had written down the story of the hunt the day the record buck was killed and he remembered vividly. But events made him give up hope of being listed in the records.

Several years ago, I wrote a column for the Minneapolis Tribune pointing out the mystery of the world-record antlers. Later, I got a call from a reader who said that the hunter might he an elderly man who lived near the St. Croix River, which flows between Minnesota and Wisconsin. I looked the man up: his name was Jim Jordan. I wrote about the story he told me in the Tribune in 1977, and that attracted the attention of officials of the North American Big Game Awards Program, now administered jointly by the Boone and Crockett Club and National Rifle Association. They investigated, and in December of 1978, the Boone and Crockett Big Game Committee recognized Jordan as the man who shot the record buck.

The story begins on November 20, 1914, a clear, sunny morning in northwestern Wisconsin. a morning that dawned on six inches of new snow over the vast stretches of Wisconsin’s woods. Jordan, who lived on a small farm near the little town of Danbury, woke up particularly early. He looked out and liked what he saw: his farmyard freshly covered with snow. It was the opening day of Wisconsin’s deer season, an event that Jordan never missed. He was 22 years old, a woodsman, logger, and trapper, and he loved deer hunting most of all.

Jordan hopped out of bed, dressed quickly, and hustled out to the barn to harness his horse to a buggy. He wanted to be ready when Egus Davis rode up. Davis arrived on schedule, unsaddled his horse, and threw his gear into Jordan’s buggy. Together. the two quickly headed into Danbury, bought their 50-cent deer licenses, and turned the horse and buggy southward toward the Yellow River.

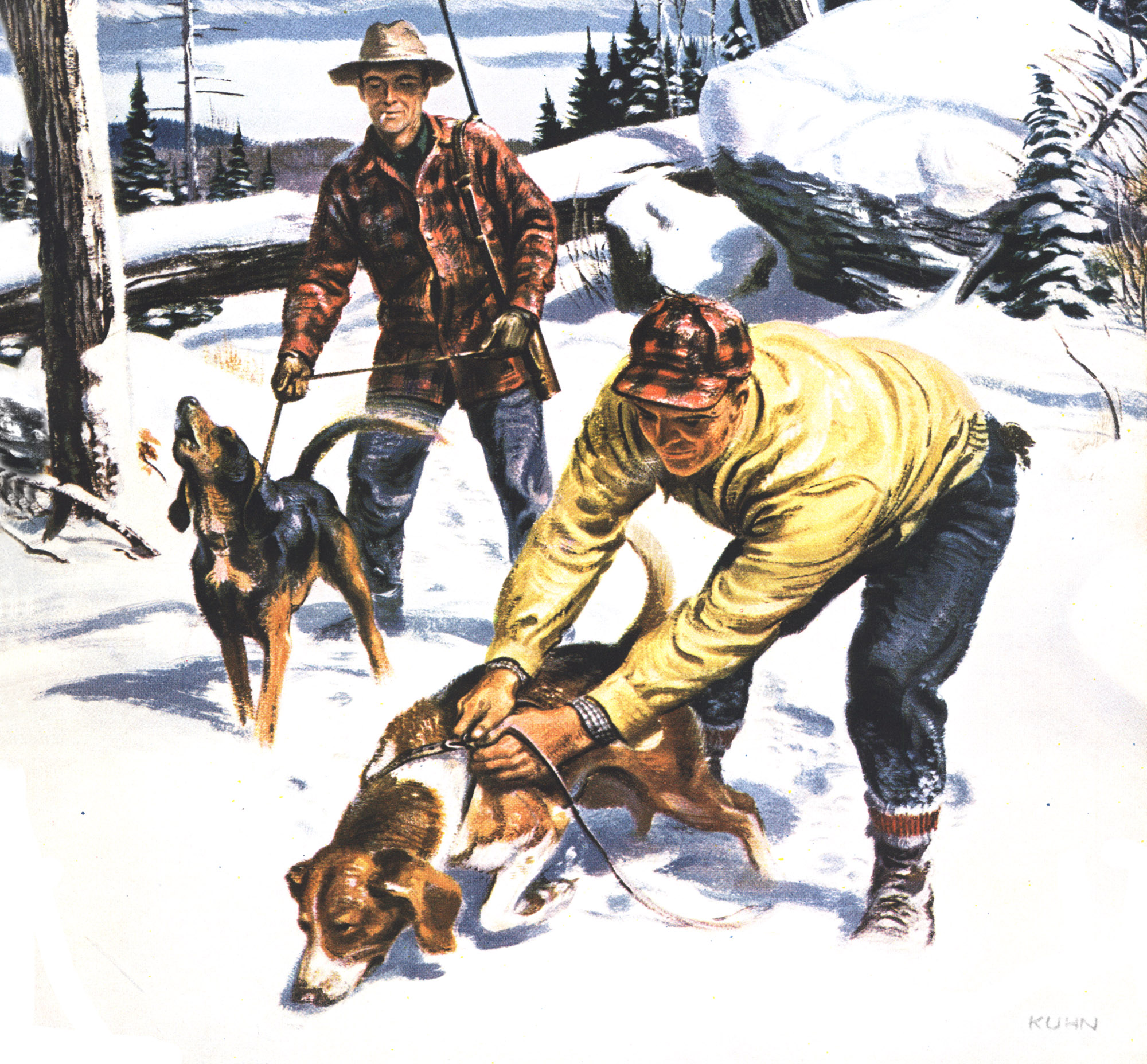

When they arrived where they wanted to hunt, Jordan tied his buggy horse, and the two hunters headed into the aspen timber on foot. They had hunted in the familiar woodlands during previous deer seasons. Today. they planned to hunt together rather than split up; Davis discovered that in the rush to open the deer season, he’d forgotten his hunting knife.

As Jordan anticipated, the hunting conditions were ideal, thanks to the new snow. Quietly, softly, the two trudged toward the Yellow River. They hadn’t walked far when Jordan spotted a doe, raised his rifle, and fired. The big doe fell. Davis was elated by the quick success. He suggested that they drag the doe back over the short distance to the horse and buggy. But Jordan was impatient. He handed his hunting knife to his friend. “Here’s my knife. You can have the doe, but you also can take the deer back by yourself. I want to keep going,” he told his hunting partner. Davis nodded his approval and Jordan, minus his hunting knife, headed off by himself.

He hadn’t gone far when. up ahead in the virgin snow, he spied a string of pockmarks meandering through the aspen thicket. From a distance, he knew the tracks had been made by deer. and he knew they were fresh because of the overnight snowfall.

His attention was drawn immediately to the set of supersize hoof prints. He couldn’t resist the temptation to follow. He checked his Winchester lever-action rifle one more time; it was loaded, but the magazine wasn’t full. The buck that made those imprints in the snow might not be far away. He quickened his pace.

The fresh deer tracks wandered southward for a few hundred yards and then turned back north toward Danbury and closer to the Soo Line railroad tracks that roughly paralleled the course of the Yellow River. Jordan continued until the deer trail led toward an opening, the railroad right-of-way. The wandering deer — there were three of four sets of tracks, including the giant buck — had probably crossed the railroad and continued, he thought to himself.

Suddenly, Jordan heard the familiar whistle of an oncoming Soo Line freight train. He paused near the open swath in the aspen. A quick glance at the trail told him the deer had not crossed the tracks. The fresh sign ambled along the grassy strip between the tracks and the timber’s edge. He had a good, clear view north and south on his side of the railroad bed. Still, he couldn’t spot the deer that had made the tracks he had been dogging. The train whistled again, still a long way down the track.

Suddenly, just ahead, Jordan saw movement — heads raised up out of the heavy, tall grass along the rail road tracks. The bedded deer were alerted by the oncoming train. There were three deer or four. Jordan wasn’t sure. His eyes were already glued to the third one that appeared above the snow-laden clumps of grass less than 100 yards away. It was a huge buck.

Jordan didn’t hesitate. He quickly shouldered his 25-caliber Winchester and steadied the iron sights on the big buck’s neck. The deer remained motionless, listening for the train, and unaware of Jordan’s presence. The buck was poised, head high, his enormous head ornament shining in the sunlight of the cloud-free morning. Jordan squeezed the trigger.

The rifle bucked but Jordan’s eyes never left the huge deer. The does bounded for the jungle of aspen. The buck went in the opposite direction. Jordan fired again, then again. Once more, and that was the last cartridge in the rifle. The speeding buck disappeared.

Jordan was quite sure he’d hit the buck once if not twice. What’s more, tracking conditions were still ideal. He figured he’d catch up with that buck again, sooner or later. Sooner, probably, if the animal was seriously wounded.

He quickly picked up the buck’s trail. Anxiously. he followed the buck’s bounding footprints, looking for blood. Then he remembered his empty rifle. He paused and dug frantically in his coat pockets for more ammunition. He had, he discovered, only one more cartridge. His last shot would have to be fired at close range.

Jordan continued to follow the buck’s trail. He found blood, not much, but some. He trudged on. The buck seemed to be heading toward the Yellow River. Jordan didn’t mind at all, for the river flowed not far from his farmstead. Suddenly, about 150 yards away, he caught a glimpse of the giant whitetail. He raised his rifle, then lowered it. With only one shot left, he decided to wait for a closer shot.

The whitetail headed for the river where it turned west. Jordan was not far behind. He now saw the buck most of the time as it stumbled toward the river. At the river’s edge, the buck stopped, his massive head and neck arched low above the ground. Jordan continued to close the distance between them. Suddenly, the buck plunged into the shallow river, struggled against the current, and stepped out on the far bank. By that time, Jordan had also reached the river’s edge. Again alerted, the mighty whitetail raised his head and looked back.

“He looked right at me,” Jordan told me years later. “I aimed at the backbone this time because he was such a big deer; I didn’t think my rifle could bring him down if I didn’t hit him there.” Indeed, Jordan’s Model 1892 Winchester, firing the pipsqueak .25/20 cartridge, was really inadequate for deer hunting.

Jordan fired his last shot; the huge whitetail collapsed.

Jordan rushed across the shallow river, oblivious to the icy water that poured into his hunting boots. The buck hadn’t moved. For the first time, Jordan could take a close look at the marvelous whitetail. Never had he seen such a set of antlers. Never had he seen such a heavy deer. He reached for his hunting knife, then he remembered. He had loaned it to Egus Davis.

No problem, Jordan thought. If his calculations were correct, he wasn’t much more than a quarter-mile from his farm. He’d walk back to find Davis and get his knife.

Davis had already returned to the farm with the horse and buggy and the doe. Jordan told of his hunting luck. Then he and Davis hurried back toward the river where the big buck had fallen. But when they arrived, there was no buck in sight.

“The buck must have flopped one more time and slid into the river,” Jordan explained. “I went down to the bend of the river and there he was, hung up on a big rock. I waded out in water waist-deep to get to him. Later, it took a whole bunch of us to pull him home. I can’t remember if he weighed just a little over 400 or just under 400 pounds.”

The news of Jordan’s mammoth whitetail spread quickly. Neighbors and town folk rode out to take a look. One of them was George Van Castle, who lived in Webster, about 10 miles south of Dan bury. He worked on the Soo Line Railroad, but he also did taxidermy work in his spare time. He greatly admired Jordan’s trophy and offered to mount the head for $5. Jordan accepted. He’d seen plenty of big bucks, but none as big as his. Van Castle picked up the unskinned head and caught the Soo Line south to his home in Webster. Jordan didn’t know it then, but he would not see his prized whitetail trophy again for more than 50 years.

Shortly after Van Castle agreed to mount the head, his wife became sick and died. Troubled by the loss of his wife, Van Castle decided to move to Hinckley, Minnesota. But he never told Jordan, who waited for months but heard no word about his mounted trophy. Finally, he made a trip to Webster, where he learned that Van Castle had gone to Hinckley, and so had his mounted whitetail.

Jordan considered making the trip from Danbury to Hinckley to reclaim his deer, but such a trek was not easy. Although the towns were only 25 miles apart, they were separated by a long bridgeless stretch of the St. Croix River. Time passed. Eventually, a new bridge across the St. Croix connected Danbury and Hinckley. But by that time, Van Castle had married again and moved to Florida.

“I never heard from Van Castle again,” Jordan recalled. He gave up all hope, of seeing his whitetail trophy again. He and his wife, Lena, moved to a small acreage near Hinckley, along the Minnesota side of the St. Croix. He was not a young man anymore, and life had not been easy. Still, he hadn’t lost his interest in deer hunting. He shot his share of good bucks. Their many racks hung from the rafters of the Jordans’ home, and he could easily tell when, where, and how each had been taken. He started collecting deer antlers as a hobby. That hobby led to still another twist of fate.

One day in 1964, a Minnesotan by the name of Robert Ludwig was strolling down Main Street in Sandstone, a small town about eight miles from Hinckley, Ludwig was a shirt-tail relative of Jordan’s, and he also collected antlers. He came to a rummage sale on a vacant corner lot. The goods — dishes, antiques, furniture — were the usual assortment. One item, however, caught his eye. It was an old, dusty, decrepit, mounted deer head. Ludwig looked it over. The mothy head had been stuffed with yellowed newspapers and homemade plaster, and it had been sewed up with twine. But the antlers were magnificent. Ludwig couldn’t believe their size. The rack, massive and perfectly shaped with five equal points on a side, was larger than any he had collected.

Ludwig paid $3 for the head and took it home. His wife was less than over joyed at his bargain. The mount was beyond repair, but the antlers were huge. Ludwig, a forester for Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources, became curious about his $3 antlers. He obtained an official form for measuring typical whitetail racks and measured the huge rack himself. He wasn’t sure what the total point score meant, but he sent his results to a St. Paul naturalist, Bernie Fashingbauer, an official measurer for the Boone and Crockett awards program.

Fashingbauer thought Ludwig’s measurements must be wrong. If they were right, the rack qualified as a new world-record typical whitetail buck. He contacted Ludwig and arranged to see the big rack and to take his own set of measurements: an unbelievable score of 206 5/8, a world record.

The score was submitted to Boone and Crockett officials, who asked for measuring by a panel of experts. The experts came up with the same score. Ludwig had indeed found the new world-record typical whitetail rack. He couldn’t wait to tell his friends and relatives — particularly Jim Jordan, since Jordan was also interested in big antlers.

Jordan looked at the record rack when Ludwig showed it to him. He was stunned. It was the same rack he had lost 50 years ago to Van Castle, the taxidermist.

Ecstatic about the discovery, Jordan had a picture taken of himself with the record antlers. He showed it to old friends who had seen the head five decades ago. They agreed it looked like the same buck. Ludwig, however, disagreed. Four years later, in 1968, he sold the record head for $1,500 to Charles T. Arnold, a deer antler collector from Nashua, New Hampshire. Arnold still owns the record rack, which has since been remounted and refurbished with a new cape.

The 64-Year Hunt for Jim Jordan’s Record Buck

1914 – Jim Jordan shoots an enormous whitetail buck on November 20. George Van Castle offers to mount the head for $5. Jordan agrees, and Van Castle takes the unskinned head to his home in Webster, Wisconsin.

Later, Van Castle moves to Hinckley, Minnesota, but does not inform Jordan.

Years later, Jordan visits Hinckley to see Van Castle, but the taxidermist has moved to Florida.

1964 — Robert Ludwig, a distant relative of Jordan, buys the Van Castle mount for $3 at a rummage sale in Sandstone, Minnesota. The cape has deteriorated. Ludwig shows the trophy to Jordan, who is sure that it came from the buck he shot in 1914.

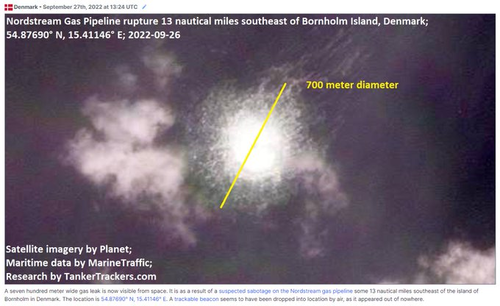

Ludwig measures the rack and sends the Boone and Crockett form to Bernie Fashingbauer, an official B&C measurer, who measures the antlers again at 206 5/8 points-a world record. The rack, later measured by a B&C committee, is officially recognized as the No. 1 typical whitetail, hunter “unknown.”

1968 — Ludwig sells the rack to Charles T. Arnold of Nashua, New Hampshire, a collector of antlers. Arnold still owns the trophy, which he is refurbishing with a new cape.

1977 — As a result of a story by Ron Schara in the Minneapolis Tribune, the Boone and Crockett Club begins investigating Jim Jordan’s claim.

1978 — The club officially recognizes Jordan as the man who shot the world-record typical whitetail. Jordan died two months before the recognition.

So Jordan was separated from his trophy, although he continued to insist it was the same buck he killed in 1914. He also insisted he wasn’t interested in any of the money Ludwig received for selling the world-record head.

“I just want to set the record straight,” Jordan told me in the fall of 1977. Of course, the record eventually was set straight when the Boone and Crockett Club credited Jordan with killing the world-record whitetail buck. But the long hunting adventure took one more bizarre twist when the announcement was made in December 1978.

Jordan never heard it. Less than two months before his record claim was officially accepted, Jordan died at the age of 86.

Read the full article here