The World-Record Muskie That Turned Out to be a Hoax

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in the December 1992 issue of Outdoor Life. The IGFA currently recognizes Cal Johnson’s 67-pound, 8-ounce muskie as the world record.

September 1957 had been, Art Lawton recalled, a “miracle” month of muskie fishing. The muskies in New York’s St. Lawrence River had been on a feeding ramp age, and Lawton along with his wife, Ruth, had been there to intercept them. The couple had taken 30 muskies weighing from 18 to 49 pounds in one week of fishing. And with hopes of catching even larger fish, the two returned one week later. Sunday morning, September 22 was an “ideal muskie day,” according to Lawton. It was cool with a hazy overcast and a slight riffle on the river just south of Clayton, New York.

“We’d been trolling about four hours when the strike came at about 11 a.m.,” Lawton wrote in an article published in the June 1958 issue of Outdoor Life. “I had him on, fighting deep, for half an hour before we saw him. All that time he did what he wanted. Then he came to the top, flailed, and tried to jump, but he couldn’t get his big belly clear of the water.

“It took me an hour to subdue him and get him to the boat. When it was all over we knew he was the biggest muskie we’d ever taken, but it didn’t occur to us that he might set a new world record.” Arthur Lawton laid claim to the then-new muskie world record with that fish, which he claimed weighed in at 69 pounds 15 ounces and measured 64.5 inches. Or did it? That was 35 years ago. On August 6, 1992, shortly after my submission of an exhaustive research paper on the Lawton fish, the world-record muskie was almost unanimously disqualified, on the grounds of falsification, by the review boards of both the National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame (NFWFHF) and the International Game Fish Association (IGFA).

A whirlwind of controversy the likes of which the fishing world has never before seen has since followed. My investigation began about seven months ago after reading an article alleging the catch, falsification of the former world-record muskie, taken by Louis Spray in Wisconsin’s Chippewa Flowage in October 1949. The article claimed that Spray’s 69-pound 11-ounce muskie was actually caught by a mobster, who sold it to Spray for $50. As the director of the Sawyer County Historical Society, owner of a lodge near where Spray’s fish was caught, and a muskie fishing aficionado, I took great interest in the story and set out to investigate it. Many avenues of that investigation pointed to Art Lawton’s world record status and the rumors that surrounded it. Ironically, and perhaps understandably to some, it was Spray himself who first raised suspicions about Lawton’s claim to the world record. After seeing a photo of Lawton’s stringer of nine muskies in a Rochester (New York) Times Union article, the largest of which was identified in the photo caption as the record fish with the next largest weighing 49 pounds, Spray raised questions.

Citing his experience as an accomplished muskie angler, Spray alleged that “either the fish [fifth from the left] weighed more than 49 pounds, or the one next to it didn’t weigh 69 pounds.” Spray declined to contest the Lawton catch, fearing his being labeled a poor sportsman.

Contest coordinators at Field & Stream magazine, the fish-record-keeping organization at the time, had suspicions, as well, following rumors about Lawton’s fish, but they were unable to find any proof of falsification. The key to my investigation into the Lawton fish boiled down to mathematical analyses of Lawton’s muskie photos and a study done on fish markings. The key photograph (what I call the “post photo”) depicted Lawton standing next to the “record” fish hanging on a post. After obtaining confirmation that Lawton stood 5 feet 8 inches tall, the true length of the fish could be calculated with great accuracy.

Precise calculations from this photo reveal that the true length of the Lawton fish was between 55.1 and 55.9 inches, and that it could not have exceeded 57 inches. This is certainly far short of the 64 inches that Lawton claimed in his application to Field & Stream for world-record recognition. (A letter recently discovered among Lawton’s personal effects by muskie fishing historian Larry Ramsell indicates that Lawton himself referred to the fish as measuring 55 inches.)

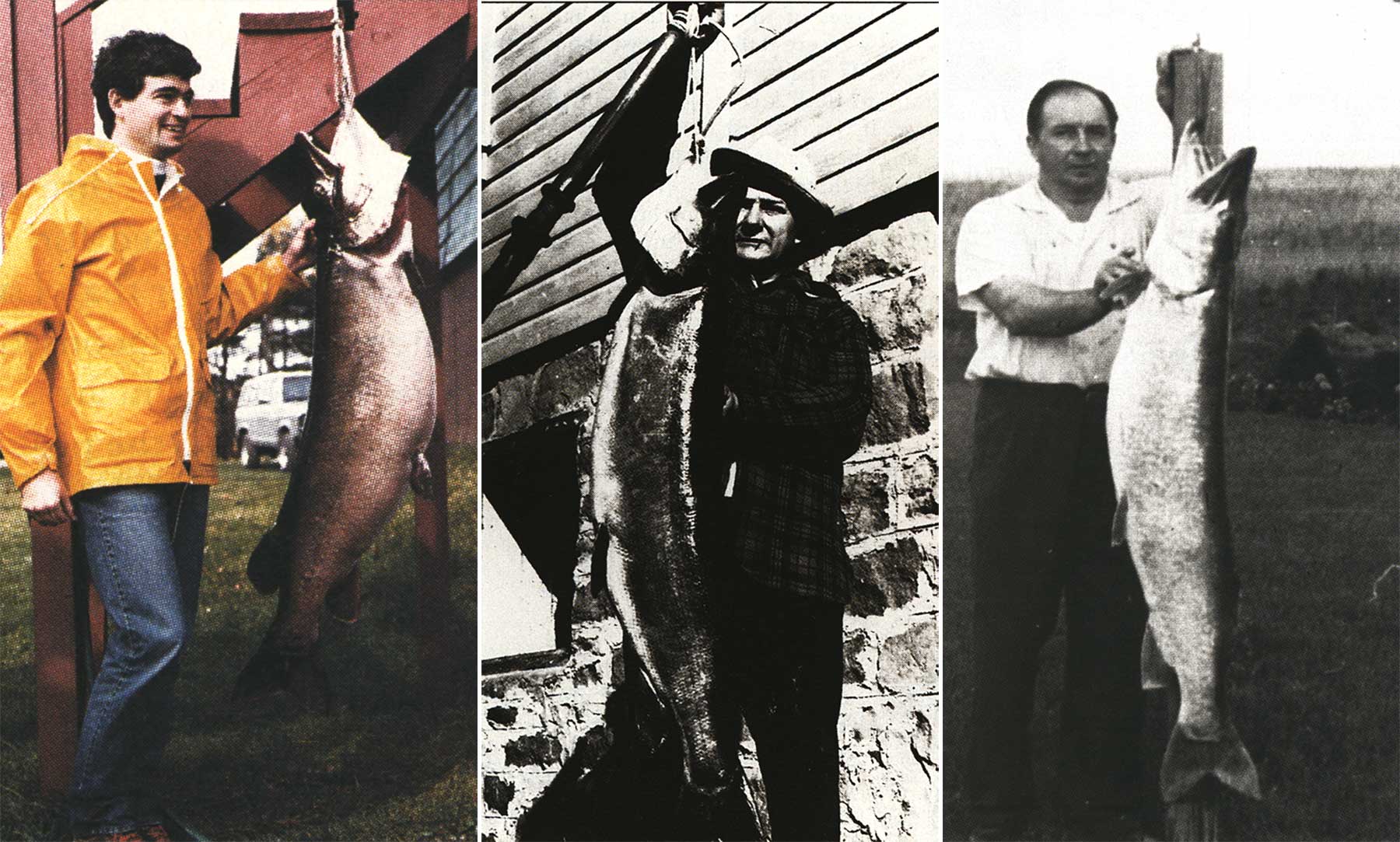

If the muskie in the post photo measured 55 inches, then so did the fish depicted in the official Field & Stream photo (a different picture). Marking studies show that they are, indisputably, the same fish, because markings, like fingerprints on humans, cannot be identical on any two fish. The third key photo in the investigation is what I call the “smoking gun photo.” This picture shows the Lawtons posing with a stringer of nine muskies. Markings on the largest fish prove it to be the same fish as in both the post photo and the official photo sent to Field & Stream by Lawton. The nine fish were, according to Lawton himself, caught a week before his alleged world record catch.

Although I felt qualified to make a complete photo analysis, I sought the services of Roy Mcjunkin, an expert in the evaluation of vintage photographs from the University of California at Riverside; Arthur Oehmcke, former muskellunge culturist and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources- fisheries manager; and attorneys· James A. Olsen and P. Scott Rasset of the Madison, Wisconsin, law firm of (ironically) Lawton & Cates. All concurred that the muskie depicted in the post photo, the muskie in the official Lawton contest photo and the largest fish in the stringer shot are the same fish. So what does this all mean?

In the smoking gun photo, which appeared with Lawton’s June 1958 article in Outdoor Life, the largest fish of the catch is said to have weighed 49 pounds 8 ounces. Notations at the bottom of the original photograph (enhanced in an effort to make them readable), which were presumably written by Lawton, also identify the fish as weighing 49 pounds 8 ounces. If this fish, according to the marking study data, is the same muskie as the one in the post and Field & Stream photos, then it did not weigh 69 pounds 15 ounces, as Lawton claimed, but was actually the 49-pound 8-ounce muskie caught one week before Lawton claimed to have caught the world record. In addition, the girth-length-weight relationship study proves beyond a doubt and certainly to the satisfaction of the NFWFHF and IGFA that the Lawton fish as pictured in the post photo could not have possibly weighed 69 pounds 15 ounces but was rather 49 pounds 8 ounces. The accepted formula for calculating a muskie’s weight from knowledge of its length and girth is: girth (squared) x length/800 =weight.Although fairly accurate, I chose to apply my data from nearly 1,000 muskies to further finetune this formula. One formula does not work for muskies of all sizes because the bigger a muskie grows, the fatter its body grows relative to its length.

Therefore, a larger divisor is required to make the formula work for heavier fish. My revised formula usually yields weights within three pounds of a muskie’s actual weight, and they are rarely more than five pounds off. Having already calculated that the Lawton fish was a maximum of 57 inches, knowing its girth would yield the approximate weight of the fish. To do this by the aid of a photograph, calipers must be used to determine side width (SW). Through much calculating with my available data for large muskies, I’ve extrapolated a formula-2(SW-1)+2(.58) (SW) = girth-to determine the girth. Tests on muskies with known weights indicate an accuracy within one inch.

Plugging in the length of the Lawton fish (57 inches) and the side width (9 inches), the muskie’s girth calculates to be 26.34 inches. Plug these numbers into my formula used to calculate weight and we come up with 48 pounds 9 ounces. Given my admitted margin of error, Lawton’s fish most probably weighed the 49 pounds 8 ounces indicated in the notations at the bottom of the smoking gun photo.

Read Next: The Most Insane 12 Days of Muskie Fishing in Wisconsin History

In his affidavit submitted to Field & Stream magazine, Lawton identified five witnesses to his catch. After considerable effort, I was able to contact four of the original witnesses. Four of the five were, in some way, related to Lawton.

Walter J. Dunn, according to the affidavit, was in charge of the weighing, and personally measured the Lawton fish. However, when I contacted Dunn (who is not related to Lawton) he said that he did not weigh or measure the fish and did not know who did. He then signed a notarized statement to that effect. The evidence is quite overwhelming that Lawton’s muskie catch was falsified. Both the IGFA and the NFWFHF have elected to disqualify the Lawton catch.

A Temporary Record

Although the National Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame has decided to recognize the Louis Spray fish as its new (old) world-record holder, the International Game Fish Association has dubbed a 65-pound muskie caught by Toronto angler Kenneth O’Brien as its “temporary” world record. O’Brien’s huge muskie was taken from Ontario’s Georgian Bay and is the largest caught anywhere in more than 25 years.

Had the fish been taken in the spring when it would have been full of eggs, it could have weighed as much as 78 pounds. O’Brien and two friends were actually fishing for walleyes when the big fish struck his Countdown Rapala. In fact, O’Brien had never even seen a muskie before October 16 1988. To say that they were poorly equipped to handle a fish of that size is an understatement. O’Brien was using a light Fenwick rod, Mitchell spinning reel, and eight-pound test. Just 15 minutes after it struck, the 58-inch muskie appeared on the surface. O’Brien was shocked at its size and knew immediately that their landing net would be useless on the fish. The anglers had luckily brought along a gaff. The first attempt was fruitless, but with O’Brien’s buddy, Mark Aristone, on gaff for the second attempt, they brought the fish into the boat.

Read the full article here