The Legendary Cowboy Who Caught More Than 1,000 Wolves With His Bare Hands

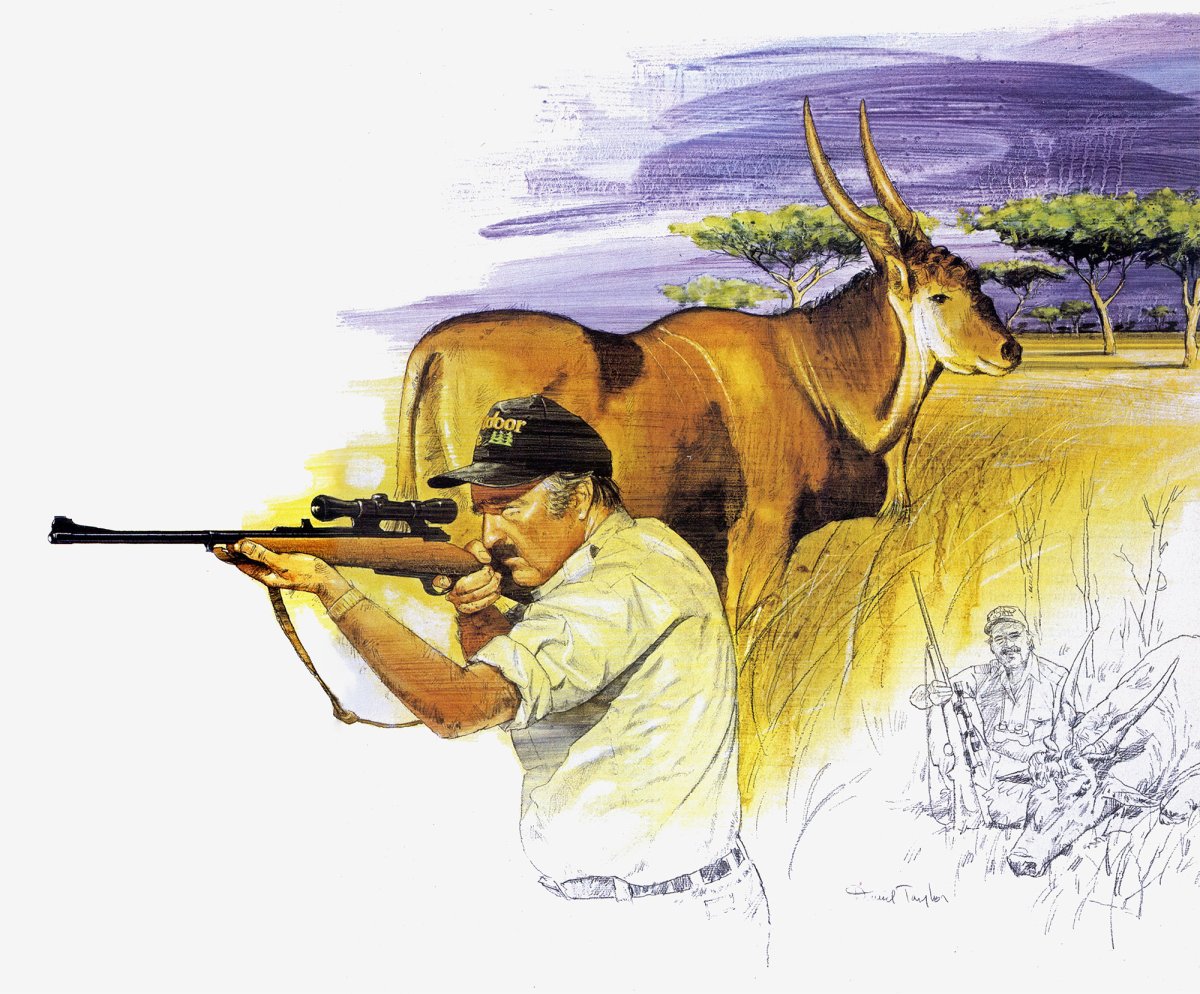

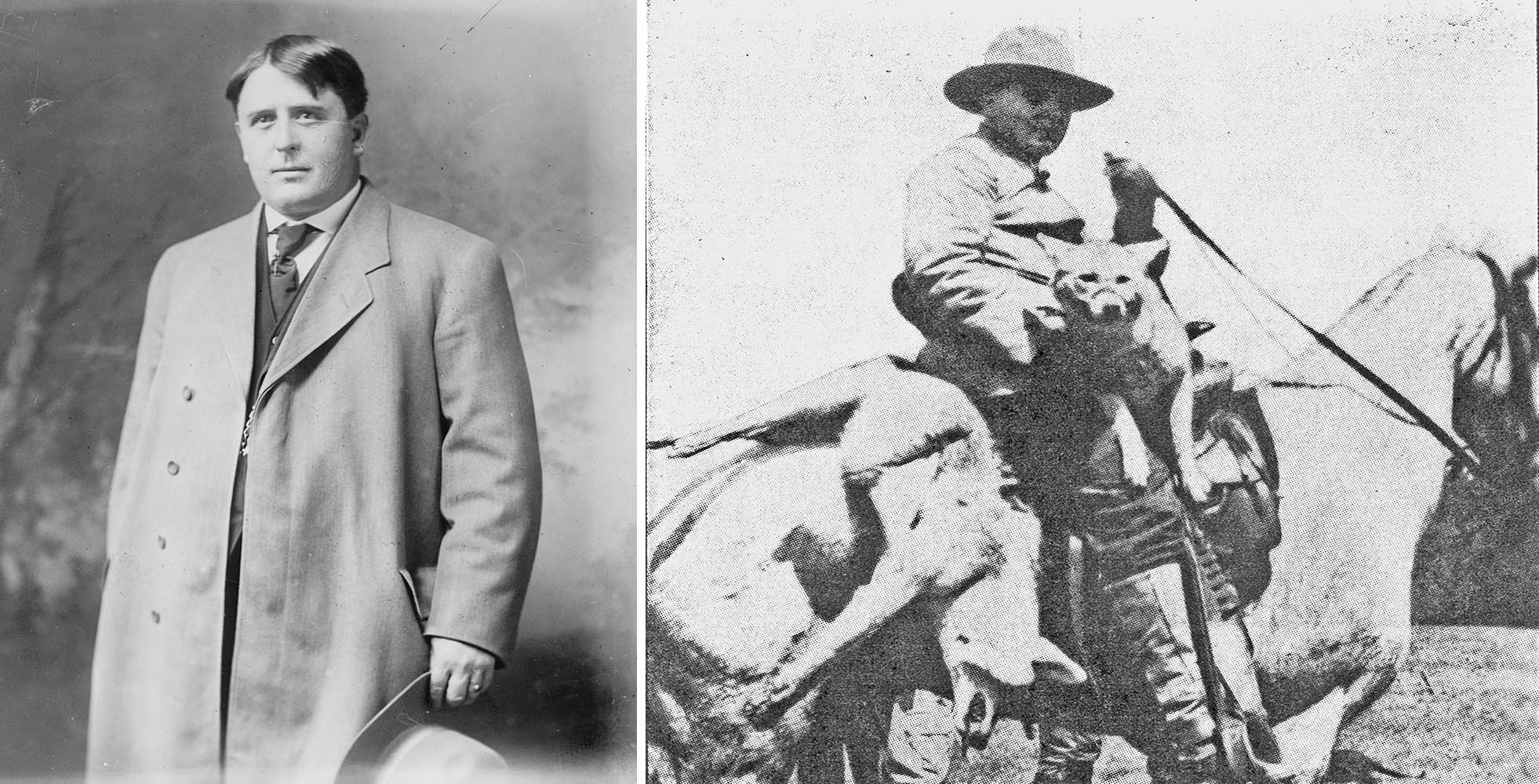

Editor’s Note: This story about “Catch’em Alive” John Abernathy was originally published in the August 1932 issue of Outdoor Life. Abernathy’s exploits as a professional wolf-catcher gained wide publicity and eventually won the admiration and friendship of President Theodore Roosevelt. The president eventually appointed Abernathy the United States Marshal for Oklahoma Territory. What follows is Abernathy’s first story of the highlights of his career, told to OL editor Monroe H. Goode. Disclaimer: this story includes some violent anecdotes, in which dogs are killed.

The dauntless courage displayed by a faithful dog in mortal combat with a ferocious lobo was responsible for my career and took me from the cow camps, never to return.

It was the spring of 1892 and the annual round-up of the north plains country was about to commence. Although only sixteen years of age, I was a full-fledged cowhand on the Goodnight Ranch, commonly known as the JA Ranch. As we were starting on the drive, our range boss came to me and said: “Abernathy, I know how well you like to hunt, so I am going to make an exception in your case and let you take your two greyhounds with you on the round-up. You may have a chance to get yourself a wolf.”

I greatly appreciated this courtesy, for I preferred wolf-coursing to any other form of outdoor sport. I had participated in hundreds of chases before and my dogs had killed many of the small prairie wolves; or coyotes, but they had never caught a lobo, which is a very large animal corresponding to the big timber wolf of the North; so when I spotted two lobos on the second day out, I started the chase with considerable misgivings.

Perhaps my feelings were akin to those of a commander whose troops were about to experience their first baptism of fire. The fleet greyhounds soon drew away from me, and I in turn outdistanced my companions.

The race was a spirited one and several miles were covered before my dogs overtook the hindmost wolf, a ferocious animal of huge proportions. A terrific fight ensued. By the time I arrived on the scene, the large wolf had slashed one of the dogs across the belly and the poor creature’s entrails were dragging the ground, rendering her ineffective as a fighter.

Hesitating not a moment the wounded dog deliberately placed her hind legs on the entrails and gave a vicious jerk in a vain effort to tear them out so as to get at the wolf. This was the nerviest thing I had ever seen.

The wolf was getting the best of the other dog and I knew that unless I intervened, he would seriously wound him, too. I was so incensed at the lobo that, throwing discretion to the wind, I leaped off my horse and entered the fray. The wolf at once turned upon me. I threw up my right hand and by accident thrust it directly into the wolf’s mouth and we rolled over in the dust. Instantly realizing that if the wolf closed his jaws I would be severely injured, I pressed my right hand as far back into his mouth as possible, grasped his under jaw firmly, and found that he was helpless so far as biting that hand was concerned.

We lay there, the wolf struggling with his body but apparently unable to do me any injury. I placed my left hand over the wolf’s muzzle, which greatly assisted me in steadying the struggling animal, but I failed to take into consideration the dexterity of his powerful paws and paid dearly for my shortsightedness. Just when I thought I had him at my mercy, he gave a quick jerk with a front leg and succeeded in breaking my hold on his muzzle, but I still held onto his lower jaw with a death grip.

In an unguarded moment I moved my left arm near his mouth, and in a flash he buried one of his sharp fangs in the flesh of my arm. It felt like the cut of a razor, and I knew that it had penetrated to the bone; the blood started flowing freely, part of it pouring directly into the brute’s mouth, and every once in a while I could hear him gulping it down.

We lay there struggling for only a half hour, but it seemed ages. I was getting weak from the loss of blood and beginning to despair of ever getting away alive, when I heard the sound of a horse approaching at full speed, and I felt sure there was someone on the horse because of the regularity of the hoof beats. The rider proved to be my brother Van, and I was never in all my life more glad to see anyone. Advancing with pistol in hand, he was just in the act of shooting the wolf when I said: “Don’t shoot him. Get that baling wire off the curb of my bridle and, we will tie him up. I want to take him to the chuck wagon alive.” And this we did.

Van and I were standing guard that night but at different watches, so I asked the range boss if we might ride together, as I had left my wounded dog 20 miles behind and I wanted to take her some food and, if possible, to do something for her.

I was grateful when he consented to the arrangement. As soon as we came off guard at 4:30 the next morning, we rode to the scene of the fight.

The sorely wounded creature evidenced her joy at our approach by beating the ground with her front paws and by wagging her tail affectionately, and, if I live to be 100 years old, I shall never forget the look of gratitude that beamed from her blood-shot, feverish eyes.

With heavy hearts, we tenderly replaced her entrails. sewed up the gaping wound, and bathed it with cool water. She could not take the food we offered but she sought to quench her burning thirst by lapping up great quantities of water from the top of my hat, which I fashioned into a receptacle.

Little did I suspect that our labor of love was misdirected. The water we thought so life-giving no sooner reached her stomach than she went into violent convulsions and, through tear moistened eyes, we saw her breathe her last.

Her death was a great loss to me, and, boy-like, I grieved for days. When the wolf slashed my arm, he tore out a part of the tendon and one end was hanging loose. We were 100 miles from a doctor, and as none of the boys would cut it off for fear that blood poison would set in if handled in such crude fashion, I bandaged the arm with a handkerchief.

Three days later I happened to pass an old abandoned shed and the first thing that attracted my attention was a pair of sheep shears — they had probably hung there for years — rusty and dust be grimed; but I clipped off the tendon with them and fortunately suffered no ill effects from my rash act.

I had had a narrow escape but I was delighted with the outcome in spite of my injured arm and the loss of my dog, because I had learned how to catch wolves alive. I have been doing it ever since, although very rarely in recent years. Incidentally, I shall carry to my grave the scar of my first encounter with a lobo.

The catching of my first wolf was purely accidental. However, since I had made the discovery, I quickly realized the possibility of handsome returns for my efforts. There was a steady demand for live wolves, many zoos being willing to pay $5 or more per wolf. I found that I could average about four wolves a day in cold weather, thus affording me a daily income of $20, less minor expenses, which was lots of money in those days at least to me. It beat all hollow the wages of $30 per month I was receiving as a cowhand.

As a result of my accidental discovery, I turned professional wolf-catcher, an occupation that afforded me much pleasure and no small amount of profit. All told, I have caught upward of 1,000 wolves, a record no man has ever sought to duplicate and one that will never be equaled, if for no other reason than because of changed conditions.

In 1901 with my newly-wed wife I took up residence on a farm near Frederick, a small town in the southwestern part of Oklahoma Territory. This section was a wolfer’s paradise and I experienced no difficulty in keeping the proverbial wolf from my door by catching live ones with my hands and selling them to the zoos, circuses, and wolf breeders. Part of my time was devoted to farming and breaking wild horses, but I considered wolf-catching my principal vocation.

The first wolf I caught after moving to Frederick deserves special mention. Accompanied by Mrs. Abernathy and Jim Wyley, a nephew, I was hunting the Comanche Indian Reservation near Deep Red Creek, a very narrow but deep stream as its name would imply, when I spotted a lobo of particular interest and determined to capture him without delay.

I knew from the way the wolf was running that he intended to cross the creek and I realized that I couldn’t get across on my horse. A few feet from the water’s edge was a high bluff, but neither the wolf nor the dog even hesitated upon reaching its brink, hurdling over it madly. I dashed up to the bluff at full speed and attempted to rein in my horse, but he was headstrong and carried me over the bank, which proved to be at least 30 feet, which was much higher than I had expected. I don’t know how I got out of the saddle, but I think I just fell out. The horse veered to the right while I was thrown to the left, landing square upon the fierce battlers. I had voluntarily entered many fights of this character, but never before had I been literally catapulted into one.

We were a queer ball of man, dog, and wolf, first one and then another being on top, but all the time rolling and sliding down toward the icy water a few feet away. Presently, in some unaccountable manner, I found I had caught the wolf by the jaw and I knew he was mine for god. Even though I was out of breath from my terrific struggles, I was pleasantly thrilled.

In the meantime my horse had climbed back up the bluff, and my wife had seen me go over the embankment, I knew she would be frantic. She started driving toward me in the spring wagon at top speed, the wagon bouncing over cattle trails and prairie dog mounds. By the time she got within 300 yards I had regained my breath somewhat and managed to climb part way up the bank; by the utmost effort I hoisted the struggling wolf, which weighed 90 pounds, high above my head for her to see, and of course, she knew I was safe. This was a very close call, and several years later when I described the incident and pointed out the exact spot to President Roosevelt, he expressed amazement at my miraculous escape.

I caught wolves in this area for some time, as conditions were ideal. The wolves were plentiful, the terrain was excellent for horseback racing; and there were no fences or farms to impede the chase. It was very seldom that a wolf got away if I had a fair run.

On another particularly interesting hunt, I had caught thirteen wolves and placed them in a cage. My wife was driving the wagon as usual and Jim Wyley accompanied me on horseback. As we were breaking camp, I suddenly decided that I wanted one more wolf. I don’t know what prompted this thought unless I figured that the number thirteen was unlucky. At any rate I made up my mind to add the fourteenth before reaching home.

W.T. Waggoner, the Texas cattle baron, had leased part of the Comanche Indian Reservation and had transferred several thousand wild, Mexican long-horned steers to the range. These vicious cattle were accustomed to men on horseback but they would attack a man on foot without the slightest hesitancy.

I had instructed Wyley to stay with the wagon until he saw me start the chase and then to follow on horseback as one never knew what might happen during a wild race. The country was full of prairie dog holes, deep ditches, and buffalo wallows, and a bad spill could be serious.

I was about three-quarters of a mile ahead of the wagon when I discovered three gray, or lobo, wolves 400 yards to the right, and I recalled at the time that it was unusual to find three wolves together so late in the morning. They peered at me for a moment, then dashed off to the south toward Red River, but shortly changed their course to the northwest, and followed a rough draw which gave them a decided advantage. This is an old trick of crafty wolves and it greatly aids them in making a safe getaway.

When they started back to the northwest, they separated, and my two dogs kept after the center wolf. Coming in at an angle at my best speed, I was unable to check my horse and as a result ran over the lead greyhound and killed him instantly. When my horse trampled the dog he stumbled and went down on his knees 30 yards but never cell completely down. However, it checked my speed enough to let the other dog get ahead. I had some rough running for a half mile, but finally the wolf took to level ground and I ran onto him in a jiffy. Dashing along by the side of the thoroughly frightened wolf, which was now doing his level best. I sprang from the back of the speeding horse and landed astride the terrified animal. The horse never slackened his speed and shortly was out of sight, the first time he ever deserted me in this manner.

I got my hold on the wolf without difficulty and was calmly surveying her fine pelage when a second wolf, a large male, suddenly appeared out of a clear sky and, like a flash, sprang upon me, inflicting a superficial wound on my right arm. It seemed that he was intent upon forcing me to release his mate, for after making the flying tackle, the wolf jumped off about 10 feet and crouched down as if to make a second spring.

Just before the wolf made his second effort, however, I thought of my knife, which I habitually carried in my right pocket, but reaching into my left pocket, much to my surprise and delight, I grasped the knife. I managed somehow to open it, and when the wolf attacked, I jabbed into his shoulder as best I could with my left hand, breaking off the only blade in the knife. This left me in a fine predicament.

I chanced to glance over my left shoulder and there stood the third wolf glaring at me and apparently ready to attack. I hardly knew what to do, or which way to turn. In the meantime, my lone dog would snap at first one wolf and then the other, holding them at bay after a fashion, but not entirely removing them from the siege.

Finally I got to my feet, still holding onto the female wolf, and started up the slope to the higher ground 200 yards away, where I thought Wyley would be able to see me and come to my rescue. I reached the edge of the elevated section without further attacks from the wolves, only to discover several hundred, long-horned Mexican steers about 150 yards away running toward me and bellowing with rage at every step.

When they got within 6 or 8 feet of me, I fell but still held onto my wolf, and the longhorns began milling around me. I could feel their breath on the back of my neck and I wondered how in the world I was going to make my escape. It looked as if my only salvation was to spring upon the neck of a steer, slip to the rear, and ride him out of the maddened herd. I was agile in those days and I knew I could stay on the back of one for a short time at least by hanging my spurs in his side.

While all this was taking place, Mrs. Abernathy had followed instructions to the letter. She had sent Wyley to the south but he failed to notice that I swung to the right and changed my course to the northwest. He continued on a southerly course almost to the Red River; then, feeling that he was on a cold trail, he took the back-track with all haste and returned to the wagon.

Read Next: Tracking Frank Glaser, Alaska’s Wolf Man

Mrs. Abernathy had been standing on the dashboard looking for some sign of me, and just as Wyley returned she discovered the milling, bellowing mass of cattle a mile away. She screamed to Wyley to ride to the cattle as quickly as possible as I might be right in the middle of them. When he reached the edge of the cattle, he fired his six-shooter several times into the air and that broke up the play.

“What in the hell are you doing there?” he shouted after discovering me lying on the ground.

I explained that I had been holding onto a wolf but that this was one time he was going to trade places with me. I pried open the wolf’s jaws and he slipped his hand in where mine had been, and the wolf closed down on him. Returning to the wagon, I drank a quart of cool water —and water never tasted so good to me before — then wired up the wolf, and landed him safely in the cage, the fourteenth victim to fall to my hands on the trip.

When I recounted this experience to President Roosevelt, he said: “Abernathy, you must promise me that you will never take such chances again. There is too much work ahead of you to risk your life in that manner.”

At the time, I didn’t catch the significance of this remark.

Read the full article here