The Hunt That Broke Jim Carmichel, and the Shot that Brought Him Back Again

This story, “Curse of the Eland,” appeared in the February 1992 issue of Outdoor Life.

Suddenly, it was all too easy. Ridiculous even. The impossible became the probable. The fool was being crowned king; the tortoise was flying to the moon. Quite simply, my crosshairs were on the eland bull, and when

I touched the trigger, nearly two decades of frustration would have a happy ending.

Of the game I had seriously pursued during my hunting career, the eland had been the only animal to steadfastly remain unobtainable. Not that I hadn’t hunted long and hard, or that I’m an unlucky hunter, it just seemed that the gods of hunting had decreed that the eland would elude me for all eternity. Like Sisyphus, the tragic figure of Greek mythology who is doomed to forever push a stone to the crest of a mountain, I seemed destined to forever follow eland tracks across the endless sands of Africa without firing a shot.

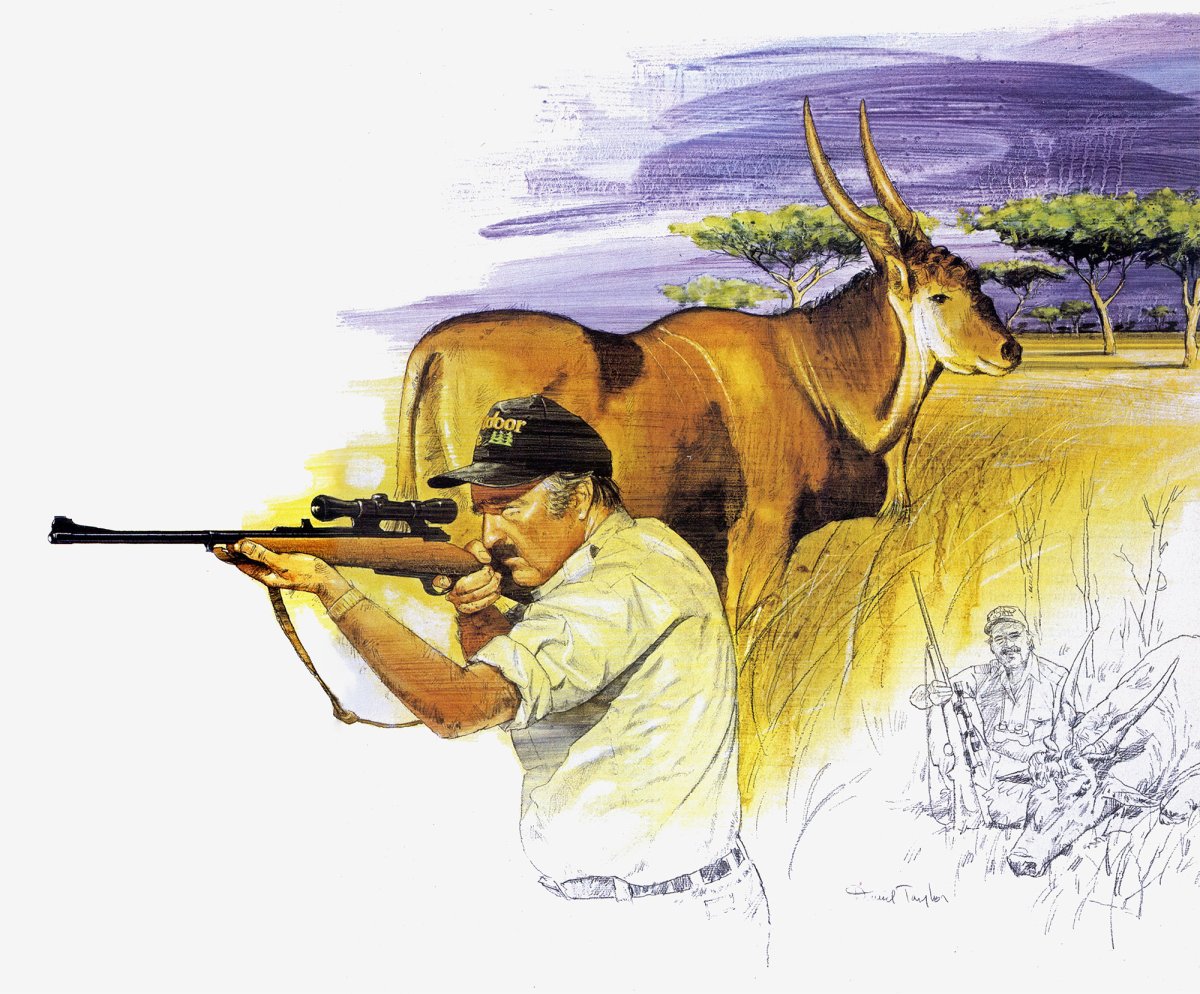

Eland are the largest of Africa’s antelope, weighing upward of a ton, with mature bulls standing nearly six feet at the shoulder. Their spiraling horns can add three more feet of height, making the eland one of the most magnificent of Africa’s game animals. With such size and impressive fighting equipment, an eland bull could be a murderous force if he was so minded, but instead eland are timid creatures that would rather run than fight. And running is something they do very well.

I learned this the first time I hunted eland. That was in Botswana back during the early 1970s when sport hunters were first discovering the hidden treasures of that remote land. It was my first safari, and like any first-timer, my ambitions were mainly focused on lions, elephants and Cape buffalo. Other species, such as eland, I planned to bag along the way whenever taken with the notion or presented with the opportunity. I hunted hard and had some good luck, but near the end of the hunt discovered that though most of my licenses were filled I was still short on eland. In fact, we hadn’t even seen an eland.

With such size and impressive fighting equipment, an eland bull could be a murderous force if he was so minded, but instead eland are timid creatures that would rather run than fight. And running is something they do very well.

Lew Games, my professional hunter, allowed that we hadn’t been seeing eland because we had been hunting in the northern part of Botswana. Eland, he reckoned, would be farther south, in the arid vastness of the Kalahari. So we packed camp into a couple of trucks and crawled south until, literally, we were up to the running boards in desert sand.

The first time I saw eland they were a long way off and running. I don’t know why they were running, they just were, covering tremendous distance in a steady, swaying trot, their enormous dewlaps swinging from side to side as they dissolved into the shimmering desert mirage.

For the next few days I learned the wrenching hopelessness of hunting eland in their own country. When other game runs away, it runs for a reason. When that reason is no more, it stops running. Not so with eland. They run for the vaguest of reasons. Even when danger is too far away to be seen or sensed they run, and they keep on running far beyond the outer reaches of danger, trot ting mile after mile like an insane marathon runner, building a barrier of distance so vast and difficult to cross that nothing can reach them. And there is no end to the land, no fence, no mountain, no river to stop them, nothing but thousands of miles of sand.

The following year I was back in the Kalahari. It was the first safari of the season and the eland hadn’t seen a hunter for months, but they were still far away and still running. In three weeks’ time I saw plenty of eland, usually in herds of 20 or more, but I never saw one that wasn’t either running or farther away than a half-mile.

A couple of years later my pal Fred Huntington and I landed in what had formerly been known as French Equatorial Africa but at the time of our safari was being ruled by a bush-league emperor who called his kingdom the Central African Empire. We had come a long way and paid a lot of money for one thing — giant eland. These are the monarchs of the eland race — larger, more colorful and wearing more massive horns. The spiraling horn of a giant eland can be four feet in length and measure more than a foot around at the base. I’d earned an eland, and now was the time to collect. With three weeks to do it in, I planned to hunt eland every daylight hour if need be. I even hired extra trackers so that if one team wore out I’d have a fresh team ready to hit the sand and pick up the trail.

During those weeks I was charged by a lion and killed a record-book buffalo. I even passed up a shot at what had to be the world-record Roan antelope, as we were on the trail of an eland, and I didn’t want to stop. But I never saw that eland — or any other. One day we followed the big tracks of a single bull for six hours. The scattered brush was such that we couldn’t see ahead for more than 200 yards, but the trackers figured the bull was just a few yards beyond. With luck we might get a shot, and I was convinced that this would be the biggest eland of all time. Mine. But then, for no reason that I could understand, the tracks became craters — the bull was running. The trackers shook their heads mournfully and slapped their legs, indicating that the eland was running hard, then pointed to the horizon. That’s when I decided I’d had it with eland.

But that all changed when Jack Slack called. Jack, a longtime shooting and carousing pal, had been the sales manager for Leupold scopes longer than the angels could remember and was about to retire. And his company wanted to show its appreciation by treating him to an African safari. Would I be interested in going, too?

Until that moment I had been suffering from African burnout: too many airports, too much paperwork, too many tse-tse flies, mosquitoes, snakes, greedy government officials and too many mean lions. But like an old warhorse who snorts to life when the bugle calls, I was ready for Africa again. Especially be cause George Martin, a good friend who heads the publications of the National Rifle Association, was coming, too.

We decided to hunt Botswana, with the arrangements and details being handled by Jack Atcheson & Sons (3210 Ottawa St., Butte, MT 59701). Our outfitter was Hunter’s Africa, the venerable safari firm that had outfitted my safari there two decades earlier. Most of the professional hunters I’d met in Botswana back then were gone, victims of time and the sudden deaths to which professional hunters are heir, but one or two were still there, elegantly polite reminders of an era when safaris were leisurely holidays of the privileged few.

Our jumping-off place was Kasane, situated near where the Chobe River joins the mighty Zambezi. It had been a squalid collection of mud huts and corrugated iron sheds 20 years before. Still squalid, the village had grown tenfold to include a service station or two, a motley collection of government offices, and rows of doorless beer joints where flies and people idled away their days. It was good to dump our gear in the Toyota hunting trucks and dash for the bush.

A happy surprise was the professional hunter assigned to me: George Hoffman — an American! By long established tradition, the ranks of professional hunters have been filled by Englishmen, Portuguese, Frenchmen, Belgians, Germans or natural-born Africans of European descent, but an American — never! Somehow it just didn’t seem proper, sort of like entering a mule in the Ascot Derby. But over the past several years a number of Americans have gone out to Africa and earned their professional license. Some have gotten themselves killed and others have just been laughable, but a small handful of Americans have proved that they can not only match their skills with the best, but even add some good old Yankee know-how. Of these, George Hoffman is the best I’ve seen in action.

I first met George long ago at a hunting conference and found him to be a keen rifleman and handloader. His pockets were filled with hunting bullets and his conversation filled with ideas on cartridge design. One

idea in particular caught my attention, a magnum case united with a .416 bullet. This was to become the .416 Hoffman, the best known and most successful of dangerous-game wildcats, eventually evolving into the .416 Remington Magnum. Thus in George I acquired not only a knowledgeable gun nut worth listening to, but a proficient, American-speaking guide. Just how good a hunter this American was I would discover before too many days had passed.

We were hunting in September, late in the safari season, and our plan called for George Martin, Jack Slack and me, each with our professional hunters, to hunt out of three separate camps during the first half of our safari. This was a mixed blessing because even though it allowed us to efficiently hunt vast areas without interfering with each other, it also meant that we would not get to share sundowners and relate the day’s adventures at campfire time. My primary interest was Cape buffalo because I was itching to try my brand-new Ruger M-77 Magnum in .416 Rigby caliber — the first ever to land in Africa, I’m told — and Federal’s Premium Safari .416 loads.

But we all know what goes wrong with the best laid plans. Mine started going wrong the moment we rolled into camp and were met by a gaggle of excited natives, all wanting to be the first to tell us what had happened during George’s absence. Nearby milo fields had been harvested and the empty fields were pushing up patches of tender grass. Eland had discovered the sweet grass and were feeding in the open fields at night.

Eland, dammit, eland, my curse had followed me. I’d promised myself not to hunt eland and had bought a license only at the last moment when George had said there was a chance we might happen across a stray bull or two. Now we were getting reports that several eland bulls had been spotted only a few miles away.

“Hold on,” I snapped, “we’re here to hunt buffalo. If we start chasing eland, this safari will go totally all to hell.” And that night I told George why; even when bewitched by the exotic incense of an African campfire and solaced by the smoky nectar of Scotland, my tales of eland remained sad ones.

Next morning we left a couple of hours before daylight — too early, I thought, for the short ride to buffalo country — and George was acting a bit mysterious. It was late winter below the equator and the morning was cold enough for a down jacket. Bietsi and Idea, George’s team of trackers, huddled shivering in the back of the Toyota, fuzzy balaclavas pulled under their chins. Our route took us past a settlement of grass huts where the last embers of the night’s fires glowed dimly and layered the still air with pungent smoke. The road sometimes disappeared altogether, and trees that had been uprooted and tossed in the trail by passing elephants had to be skirt ed and the route found anew. In places the sand was so soft and deep that we growled along in low gear for long miles.

At a place where the road grew wider and the forest began to thin there was a tap on the roof of the cab and George stopped and switched off the headlights. Bietsi, leaning down from the back of the truck, pointed into the darkness and whispered a few words to George. One of the words was “eland.” Even before he explained, I realized why George had been so mysterious.

We were near the milo fields, and George’s plan was to check out the reports that eland had been feeding there. “Get your rifle and let’s take a walk. We just might bump into an old bull.”

When we reached the edge of the milo fields we found a narrow strip of tall, dense weeds growing along a narrow dry wash snaking across the field. By following the wash and staying behind the screen of weeds, we could get to the middle of the vast field without being spotted.

Walking single file, with me at the rear, we’d gone about a half-mile when I glanced over the top of the reedlike grass and saw, to my complete astonishment, the tips of eland horns! For a long moment I just stood and watched, seeing no more than the top foot or so of the sharp horns of six or eight bulls. It was like standing behind a seven-foot wall while a silent parade passes, seeing only the bayonet tips of marching soldiers.

Realizing that only I had spotted the eland, I snapped my fingers to get the attention of George and the two trackers, who by that time were several yards ahead. Pointing toward the weeds, I held my fingers over my head to imitate the horns of eland, then touched my ears to indicate that they were very close and could hear us.

For a long moment I just stood and watched, seeing no more than the top foot or so of the sharp horns of six or eight bulls. It was like standing behind a seven-foot wall while a silent parade passes, seeing only the bayonet tips of marching soldiers.

Bietsi and Idea, both of whom are half bushman, reacted instantly, dropping into a crouch and running ahead, searching for an opening in the screen that would allow a better look at the eland. By that time there was enough light to see fairly well, and for hundreds of yards ahead the dense grass remained impenetrable. Only yards from the quarry that had eluded me for so long, I was cut off by a wall of vegetation that would stop a truck. The frustration was familiar.

As expected, the trackers never found a suitable opening, and the bulls eventually scooted out the far end of the milo field without me getting a shot.

The next morning we were at the edge of the field an hour before dawn, hiding the truck in a far corner and walking a mile or more so that we were centered in the end of the field where the eland had escaped the day before. Finding our way in the brush with flashlights, we found an overturned tree at the edge of the forest that would make a good shooting rest as well as offer concealment from the spooky eland.

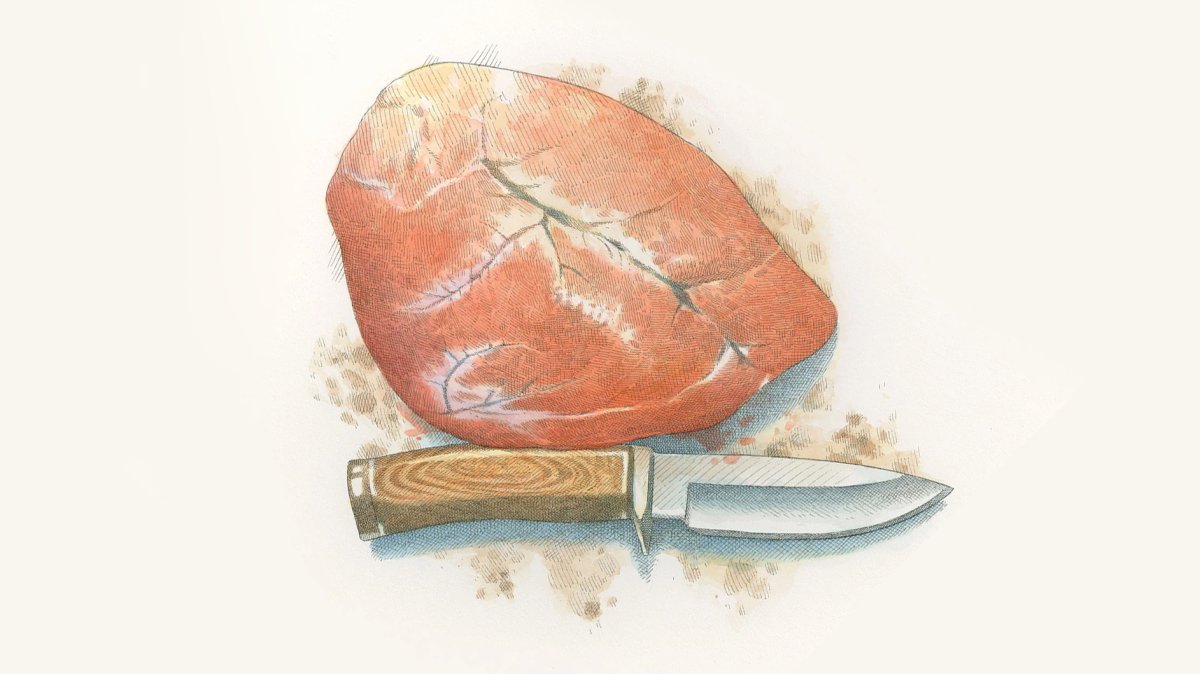

My rifle was a David Miller custom Mauser in .338 Winchester Magnum topped with a 4X Leupold scope — scarred veterans of more than a dozen safaris and Alaskan treks. For once, rather than my usual handloaded 250-grain Nosler partition bullets, I was equipped with Federal’s Premium Safari load using the same Nosler. Even at 300 yards the partition bullet would still be hitting hard, and a billboard-size eland is a hard target to miss even at that distance. From where I crouched I commanded better than a quarter-mile — from full left to right — of the eland’s exit route. Now we only had to wait until daylight. The very difficult had become the very easy and my spirits were with the clouds. Surely the eland jinx was over.

Day comes fast in the northern Kalahari. First the horizon glows with a thin line of blue sapphire, then an explosion of light blows away the night. In a matter of short minutes I could see 100 yards, 500, a mile, and then to the farthest ends of the vast milo field. Nothing! No eland! Through my binoculars I could see a pair of ostriches, their long necks reaching to the ground, but no other creature. Bietsi and Idea, who needed no binoculars, made sad clicking sounds with their tongues. They were as puzzled as George and I; there was no reason for the eland not to be there. But I understood well — my eland jinx would last forever, and having become so familiar with failure, the disappointment wasn’t all that great.

“Now you know,” I said to George, “about eland and me.” Bietsi and Idea pulled up their balaclavas for a smoke and regarded me in silence, wondering, I suppose, what sort of bad magic this stranger could have that would make huge animals disappear from the face of the earth.

Before we had traveled many paces, Idea, and then Bietsi, began pointing at the ground and making back and forth sweeping motions with their arms. Crossing tracks. Eland! The bulls had been there after all, but had left before we arrived. Perhaps lions had moved in, or possibly they had heard our truck, but they had been there in the night.

“How far are you willing to walk?” George asked.

“Until I drop.”

“Then let’s go find some eland.”

I’d followed eland before, mile after mile, and walking in soft sand is exhausting; but why not give it one more try? If for no other reason than to convince George once and for all that hunting eland with me was a hopeless proposition. But then, I didn’t know how determined George Hoffman could get.

Our plan was simple. In fact, there was no plan other than getting on the eland tracks and following. It is the most primitive form of hunting, and the purest, but following eland in their own territory is a losing game. Our only hope was for them to stop and bed down, but that would be miles into the bush, far from the milo fields of Nunga.

I carried my rifle rather than let one of the trackers do it because I knew that if we spotted eland it would only be for an instant and I would have to be ready. Once we passed a sable antelope, coal black with a white face, studying us from no more than 50 yards. After we had gone past he spooked and charged away.

The tracks wandered deeper into the bush without reason or apparent direction. Occasionally a single track or two would separate from the main group, and at other times stray sets of tracks would join the ones we were following. Follow ing the eland’s trail was not difficult; their hoofmarks were clearly visible in the sand, and in time each set of tracks came to have its own personality. We kept up a steady pace, walking fast, but even so I guessed that for every mile we covered the eland were covering two. But I was wrong.

It happened so fast that I don’t remember it well. We had been staying close together, with Bietsi and Idea walk ing in front, their dark, slightly slanted bushmen’s eyes scanning the bush ahead. Then suddenly they were on the ground, motioning me down, too. I could see nothing, but the trackers’ urgent motions told me that eland were close. But where?

“They are bedded down under the big leafy tree about 60 yards ahead,” George whispered close behind.me. “Let’s crawl ahead until you can get a clear shot.”

We kept up a steady pace, walking fast, but even so I guessed that for every mile we covered the eland were covering two.

With George at my heels, I bellied forward about 10 yards, pushing my rifle ahead. Then I found a tree big enough to stand behind and slowly raised to a standing position. Seconds later George was pressed behind me.

There, scattered before us, utterly unaware of our presence, were six mature eland bulls. They lay on their knees, bodies profiled and heads erect.

“The big one is on the far side,” George whispered. “All but his head and neck are hidden by that bull in front; you’ll have to shoot him in the neck.”

Now it was easy — too damned easy. With the animal only about 50 yards away and a tree to steady my aim, there was no way I could miss. Pinching the rifle’s safety between my fingers and moving it slowly so there wouldn’t be a metallic click, 20 years of eland hunting raced before my eyes. “By God,” I said to myself, “I’ve earned an easy shot.”

The crosshairs scarcely trembled when I settled them high on the bull’s neck, just behind his head; Then I began pressing the trigger, and kept on pressing until the .338 bucked and I lost sight of the eland. I called the shot perfect, but what I saw was a cloud of dust beyond the bull.

All I could figure was that the partition bullet had gone through the eland’s neck and kicked up dust beyond, but George was shouting, “Shoot again. Shoot again.”

But at what? My bull had to be dead, but all I could see were eland crashing into the brush, almost totally hidden by their own dust. Then there was nothing.

The feeling can’t be described. Like missing the 100th shot at the Grand American Handicap after 99 straight? No, worse. Like a girlfriend saying, “No,” to your marriage proposal after a 10-year courtship? Worse.

I had missed. For a long while I didn’t believe it, but I had missed. I told George the shot had been perfect and that the eland had to be hit and down somewhere nearby, probably dead. “Could be,” he said, “but the trackers say the bull wasn’t hit when he ran away.” But to make sure, he had Bietsi and Idea look for blood. There was no sign, and finally I accepted the fact that I had missed. The feeling can’t be described. Like missing the 100th shot at the Grand American Handicap after 99 straight? No, worse. Like a girlfriend saying, “No,” to your marriage proposal after a 10-year courtship? Worse. It was the failure to crown all failures.

I supposed there was nothing to do but head back to the truck. The sun was overhead and our hemp water bag was nearly empty. But already George and the trackers were studying the sand for scattered tracks of eland.

“Idea says the big bull went this way.”

I couldn’t believe it. Following the eland had been tough enough when we were relaxed and moving slowly. Now George was proposing that we try to keep up with a smart old bull that had just been shot at. That bull was probably already miles ahead. But what the hell, I thought, this was the way eland hunting was supposed to be. Impossible. I promised myself that never again would I hunt eland. I’d given it my best shot — literally — and hadn’t been good enough.

When we saw the eland again it was as in a dream. Why it had stopped I will never understand. Bietsi and Idea only stood motionless when I stepped in between them. In all of that thick forest, the bull and I were standing in the only place that we could have seen each other from so far — more than 200 yards. Yet the distance was only a thoughtless abstraction, as was time. Probably it took no more than a second for the crosshairs to find their mark on the eland’s chest, but everything was in slow motion. The bull was facing me straight on, head erect.

This was my final chance, a fast offhand shot. Then the rifle kicked and everything disappeared.

I heard a crashing of brush, and Idea was running ahead, Bietsi angling to the side, and the two were shouting to each other. I couldn’t understand what they were saying, and I couldn’t see the eland. Was it running away?

“They say, ‘Come quickly, you may have to shoot him again,’” shouted George. He was running, too. And then I was running, working the bolt of my rifle. The bull had run more than 300 yards with my bullet in his chest. Then he had stopped and lay down for the last time. Only then did the impossible become the real.

Read Next: Carmichel in Australia: Charged by a Backwater Buffalo

George and Bietsi went to find the truck and were gone for a couple of hours. Idea went to sleep and I sat on a log beside the eland, reliving a hunt that had begun 20 years before and finally, had ended.

Read the full article here