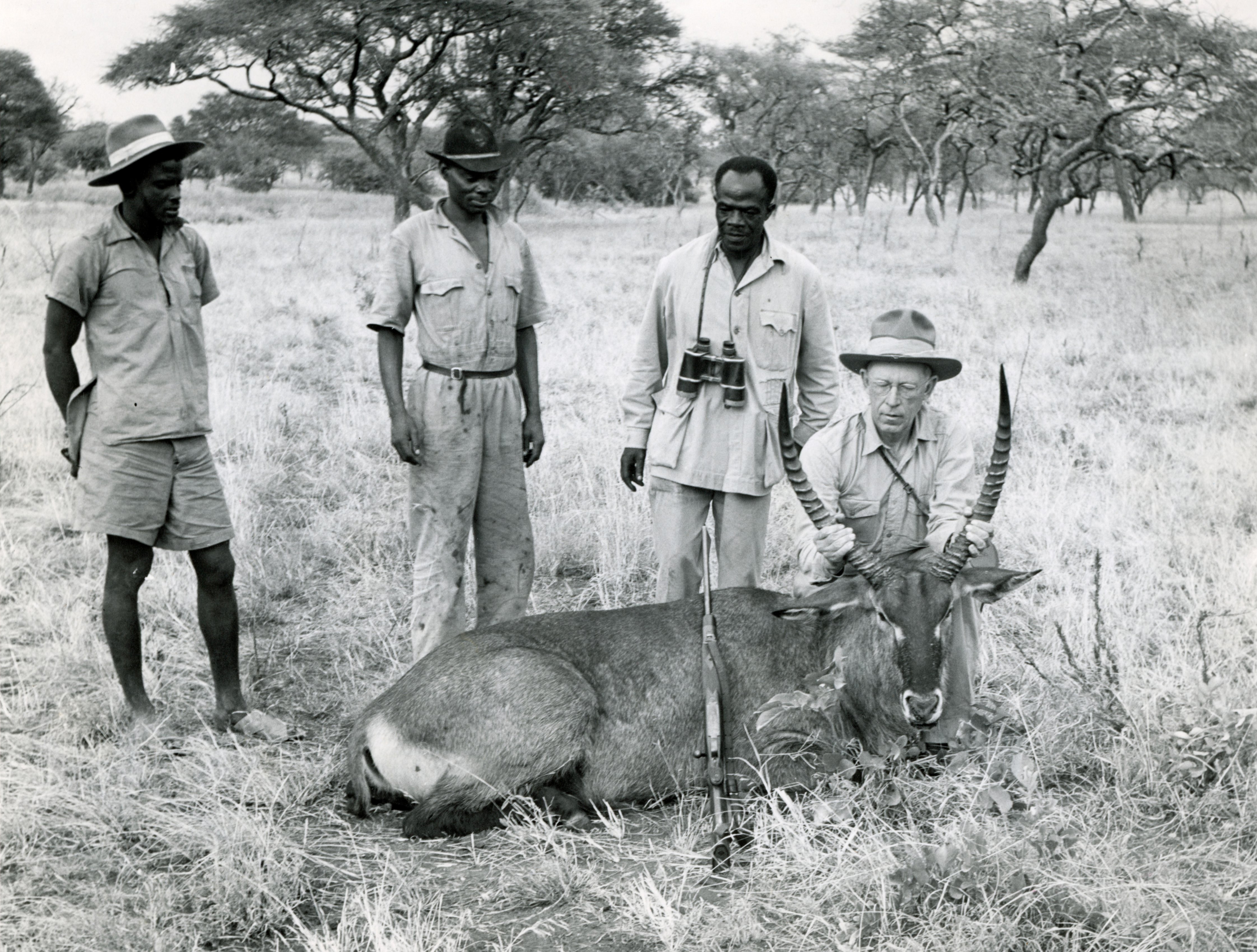

The .270 Isn’t Powerful Enough? Jack O’Connor Took His on a 30-Day African Safari

This story, “The .270 in Africa,” was originally published in the March 1967 issue of Outdoor Life. Bechuanaland is now Botswana.

My wife and I did a 30-day hunt in Bechuanaland in the summer of 1966. We shipped plenty of rifles and ammunition, but somewhere along the way the aluminum gun cases in which I had shipped our things had been looted.

All the ammunition in sight was stolen along with my cleaning rod but not the tips, patches, or solvent. Also missing were a steel tape, leather belt boxes holding 20 rounds each of .30/06, 7 mm Magnum, and .375 Magnum.

Before leaving home I had worked up a handload for the 7mm Remington Magnum that would shoot a gnat’s eye out at 300 yards. All of these lovely cartridges were gone with the wind.

Perhaps I had some vague premonition. At any rate, before I took off on the trip I put in my suitcase a box of .270 handloads, a box of .30/06 factory loads, and 10 .270 cartridges in two clips used for .30/06 ammunition with the old 1903 Springfield. In addition we had one box of .270 ammunition and two boxes of .30/06 ammunition the looters had not seen, as I had put them under the neoprene pads on which the rifles rested.

This is the ammunition my wife and I used, except for some .375 Magnum cartridges I got from John Kingsley Heath, my white hunter and outfitter. This I used on one buffalo. Everything else I shot with the .270. My wife took all her trophies with the same .30/06 she used to kill two tigers in 1965.

I have read many times that the .270 is almost as worthless on African game as a fly-swatter. In fact, I have read that the .270 “has no place in an African battery.” I have also read that all African game was so fearfully tough (even the smaller antelope) that nothing less potent than the .375 Magnum should be used on them. I have been assured, particularly by African white hunters who have never shot a single head of North American game, that African game is far, far tougher and more difficult to kill than North American game of the same size.

Relatively few paying customers have ever taken a .270 on safari, as most have been brainwashed in favor of heavy bullets.

Relatively few paying customers have ever taken a .270 on safari, as most have been brainwashed in favor of heavy bullets. In fact not one of the many Americans who had gone out with John Kingsley-Heath or his partner Frank Miller (who on this safari guided our friend Richard Harris) had ever taken a .270. Our gunbearers Kiebe and Edward had never seen a .270 rifle or a .270 cartridge and were always getting .270 ammunition and that for my wife’s .30/06 mixed up.

However, some dude hunters have used .270’s. Bob Lee, a New Yorker who has spent many months on safari and who has hunted over most of Africa, is a gun nut of the most desperate kind. He has always had a special weakness for the .270 and has shot a lot of African game with .270 rifles. His favorite load is the 150-gr. Nosler bullet in front of 58.5 gr. of No. 4831. Among other feats he once bushwhacked two big Angola lions and killed them both with two shots. He has shot two other lions with the .270, and none required a second shot.

Prince Abdorreza Pahlavi of Iran is another rifle enthusiast with wide African experience. In 1965 he hunted the great central-Asian wild sheep in the the Altai and Tien Shan mountains along the Russian-Mongolian border. He used a restocked Model 70 .270 (which I had borrowed from him to knock off three mountain sheep and an ibex in 1959) and he killed all his rams with one shot.

In 1966 he took the same rifle to Ethiopia and shot with it two of the rarest and most highly regarded of all African trophies — the best walia ibex taken in years and an excellent mountain nyala. Both animals, he wrote me, were shot at about 300 yd. and knocked off with one shot. He also shot less rare animals with the same rifle.

I had used a .270 on Sahara game in what is now called the Chad Republic in 1958 — on white oryx, addax, dama and dorcas gazelles, and Barbary sheep. I had shot a zebra, a waterbuck, and a couple of Thomson’s gazelles with a .270 in 1953. I had also used the cartridge on jungle and plains game in India in 1955 and on red sheep, urial, wild boar, and ibex in the mountains of Iran that same year.

But only on the hunt in the Sahara desert had I used a .270 as my only light rifle for African antelope big and small. In other years I had taken a .30/06, a 7mm. Remington Magnum, or a .300 Weatherby.

The first head of game I shot with the .270 on my Bechuanaland trip was an impala, a handsome and rather frail looking antelope that is about the size of an American pronghorn and would probably field dress at no more than 100 to 115 lb. The buck impala ran across the road and stopped, but before I could get out of the hunting car it had disappeared in the brush.

I followed and saw it standing about 150 yd. away. The 130-gr. bullet struck it squarely through the lungs just behind the shoulder. The buck took a convulsive jump that carried him about 30 ft. and piled up.

I shot three springbok with the .270 and 130-gr. bullets. The first was killed stone dead with a lung shot at 245 paces over flat country. The second was hit at 338 paces in the rump. He needed a second shot but did not move out of his tracks. This was the best buck we had seen. He simply would not turn broadside and was walking away when I shot.

The gunbearers got a big kick out of the fact that I had to shoot the springbok twice, as a few minutes later my wife used a little Arkansas elevation with her .30/06 to kill another springbok dead in its tracks at about 350 yd. They immediately named her Mamma Kali, which in Swahili means The Dangerous Woman.

My best shot on a springbok was at 280 paces. He was broadside, and since I had a good rest I decided to see if I could break his neck at that distance. I was lucky. It could not have been done more neatly if the little buck had been 28 instead of 280 paces away. The springbok is a small animal that would dress out at about 60 to 70 lb.

The .270 I used is a remarkable rifle. It’s a standard grade pre-1962 Model 70 Winchester featherweight which I purchased at an Idaho hardware store. The serial number is 523509. I sent to P. 0. Ackley for a piece of French walnut and Al Biesen used this to stock it. He put on a Leupold 4X Mountaineer scope with the old Tilden top mount, substituted a steel Model 70 trigger guard and floorplate for the aluminum one, put the release button in the trigger guard, and checkered the bolt knob. Otherwise the metal was untouched.

The rifle weighs 8 lb. with scope, and with good bullets it will average five-shot groups of about a minute of angle. When I shipped the rifle it was sighted in to put 3 in. high at 100 yd. the 130-gr. bullet in front of 62 gr. of No. 4831, a load which averages 3,150 f.p.s. in the 22-in. barrel of this particular rifle. A handload of a 150-gr. bullet with 58.5 gr. of No. 4831 or the Winchester or Remington factory loads in this rifle sighted as I have described land right on at about 240 yd. instead of at around 280 yd. in the case of the 130 gr.

For most hunting the two bullet weights shoot close enough together to be interchangeable. On the Bechuanaland hunt I took pains to see what bullet weight I had in the magazine only when I had an extra long shot. Then I made certain I was using the 130 gr., as it shoots a little flatter and I was familiar with the trajectory of that bullet.

A full-grown zebra weighs from 550 to 700 lb. and has a reputation for being hard to kill with one shot with any rifle. The .270 knocked off three, all with one shot. All were broadside shots-one standing at about 135 yd., another running at not over 75, and another (my wife was shooting) running at about 100. In each case the 150-gr. Speer and Nosler bullets went clear through the zebras from side to side, and no zebra went farther than 50 ft. after it was hit.

The longest shots made with the .270 were on red lechwe, a swamp-dwelling antelope about as heavy as a run-of-the-mine mule deer. One big lechwe ram had been wounded with a .30/06 by my wife (a difficult running shot at about 225 yd.). The ram went clear across a shallow lake. We went around and finally located it quite sick but still on its feet.

Deciding that it was between 350 and 400 yd. away, I took a good rest on a termite hill, held just so I could see light between the bottom of the horizontal crosswire and the top of the ram’s shoulder. I heard the bullet strike and saw the ram fall, but my shot had been low and another shot was required when John and the gunbearers got to it.

John told us about a very large lechwe which a previous client had shot at and possibly wounded some time before. After a great deal of glassing he located it over 300 yd. away out in the water near an island formed by an ancient and large termite hill.

As I got into position, the old ram decided I was up to no good and took off. I got a firm rest, squeezed off the shot but had a misfire, possibly because inadvertently I had got oil on a primer.

The lechwe was on the move, but I hit him with the bullet from the next cartridge. The soggy thump when it struck told me the shot was too far back. I held too high and led too much on the next shot and missed. I then decided to wait until the lechwe stopped.

When he did so, he was a long way off. I held what looked like 18 in. to 2 ft. above the top of his shoulder, squeezed off, and saw him go down. He was hit through the lungs and stone dead.

This was a 29-in. lechwe, the biggest head to be taken out of that section of the Okavango swamps, according to John. He had been hit a month or so before, but he had only been clipped across the paunch and the wound was healed.

A shot I particularly enjoyed with the .270 was on a good reedbuck, an animal about the size of the average whitetail. He was looking at me over a little mound and was between 175 and 200 yd. away. I could see only his head and neck. I sat down, slipped my left arm into a tight sling, and delivered a bullet that landed about 3 in. below his chin.

Incidentally, that reedbuck was one of the finest pieces of meat I have ever eaten in Africa or anywhere else. The day after I shot the buck we went on a spike camp to try to locate and stalk a lion by its roaring. Our personal boy (who was also the No. 2 cook) roasted a reedbuck ham on a spit and basted it with a sauce made of white wine, butter, and Tabasco sauce. It was a rare treat.

The Kalahari gemsbok or giant oryx is a big tough antelope about the size of a spike bull elk and with long, straight, very sharp horns. All the members of the oryx family-the fringe-ear of Kenya and Tanzania; the Beisa of Kenya north of the Tana River, Somaliland, and Ethiopia; the white or scimitar-horned oryx of the Sahara desert-are traditionally tough and hard to kill.

The gemsbok is the largest member of the family. On a safari in Kenya, shooting through brush and not shooting very well either, I once had to hit a Beisa five times with a powerful .300 belted super magnum before it went down.

My wife got the first oryx, a fine 40-in. bull. Using my .270 with the 150-gr. Speer bullet, she overshot the first time she cut loose offhand as the bull quartered away at about 175 yd. going flat out. Her second shot broke the right hip. The bull slewed around broadside, and a shot through the lungs put it down.

I got a 41-in. bull a couple of days later with the same rifle. He was running flat out at about 150 yd. when I started shooting. I thought my first two shots were misses, but it turned out that if I had been lucky either would have dumped him as both had just missed his spine just back of the shoulder hump.

He started to turn away slightly for the last shot. The 150-gr. bullet hit him high through the back ribs on the right side, went through to smash up both lungs and break his left shoulder blade. This big animal running all out at about 40 m.p.h. collapsed in mid-jump and slid over 30 ft. in a cloud of dust.

A greater kudu is another elk-size African antelope. Unlike the gemsbok, who likes open or thinly brushed desert, the kudu feels most at home in the brush and is generally found there. These big, spiral-horned antelope are very smart and wary. They are spectacular trophies, and hunting them is exciting.

The kudu is my favorite African antelope. I have hunted kudu in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Mozambique, and Angola. The bull I shot in Bechuanaland was standing under a tree with two other bulls. I shot him offhand at about 125 to 150 yd. and hit him too high. The bullet paralyzed him and he did not move, but I had to shoot him again.

I was not surprised at the results I had with the .270. I have been using the caliber ever since it came out in 1925 and have shot North American game from jackrabbits to moose with it, and that includes several black bears and a couple of grizzlies. I have also used the cartridge in India on black buck (a handsome little antelope about the size of the Bechuanaland springbok), wild boar, and jungle deer, as well as in Iran. All that amounts to some pretty fair testing.

Another reason that I was not surprised was that I have seen my steady-nerved, cool-headed wife use the little 7 x 57 Mauser in Tanganyika, Mozambique, and Angola and kill roan, kudu, sable, waterbuck, and eland with one shot. All of these are large antelope. In Angola and Mozambique in 1962, she used a 7 x 57 while I was using a 7 mm. Remington Magnum on the same game and our companion Fred Huntington was using a .280 Remington. If the .280 or the 7mm Magnum killed one bit better than the 7×57, I couldn’t see it. Actually, I think my wife got more game with fewer cartridges expended than either Fred or I did.

I was not surprised that the 150-gr. Nosler and Speer bullets went right through the rib-cages of large animals like gemsbok, zebra, and kudu from port to starboard and vice versa, bll’t I was astonished to see that the 130-gr. Nosier did the same thing. I could see no difference in results when either the 130 or 150-gr. bullet was used. Theoretically, the 150-gr. bullet with its greater sectional density and its somewhat lower velocity should give deeper penetration, and the 130 gr. with its higher velocity should expand more violently. Actually, there was no ascertainable difference in their effect on game.

The 130-gr. bullet shot flatter than the 150-gr. .270 bullet over practical game ranges and of course a good deal flatter than the 180-gr. .30/06 bullets used by my wife.

As far as actual killing power went, I could see no difference between the effect of a 180-gr. .30/06 Remington Core-Lokt, a 180-gr. .30 caliber Speer, a 130-gr. or 150-gr. Nosler .270 bullet, or a 150-gr. Speer .270 bullet. Any of them in the right place meant a quick kill. I have no doubt that if these bullets were shot under controlled conditions an autopsy might show that one gave on the average a little deeper penetration and another made a wider wound channel. But for practical purposes, one was as effective as the other.

Something many people forget is that light recoil is as great an asset for a cartridge to have as high velocity, heavy bullets, and staggering amounts of muzzle energy. Light recoil is particularly desirable in an antelope rifle for African use-a rifle that may be shot every day for 40 days.

Richard Harris, who went along with us, had a beautiful new .375 Magnum. At first he shot very well with it. He picked small antelope off at long range, made a long series of one-shot kills. Then his shooting fell off. Continual beating by the 45 ft.-lb. of recoil from the .375 had his shoulder black and blue and so tender that he was yanking the trigger. He shifted to the milder 7 mm. Remington Magnum, and as a result of the switch he quickly got over his problem with the flinches.

Hunting conditions in various parts of Africa vary as much as they do in the United States. Animals of the same species are often found under widely varying conditions. The elksize greater kudu is generally shot in brush at close range, but a fine one I knocked off in Angola was on a hillside about 300 yd. away. Bill Ruger, the arms manufacturer, made a long shot at a kudu in northern Kenya on a mountain that was bare enough for sheep.

This, I know, is going to drive the lovers of the big bores mad. The thought of anyone’s knocking off a large animal, particularly an African animal, with a fairly light bullet is almost more than they can bear.

On such long shots the important thing is precision-a combination of man, cartridge, rifle, and scope that will put all the bullets into a hat at 300 yd. or more. What caliber the hunter chooses makes little difference if the hunter can shoot it well day in and day out.

If a hunter likes a .300 Weatherby Magnum or a .300 Winchester Magnum, doesn’t mind the rather sturdy recoil, and can shoot rifles of those calibers accurately, that is what he should take. But if at home he uses a .30/06 or something of the sort and goes to a harder-kicking rifle just because he is going to hunt antelope in Africa instead of mule deer or elk in Idaho or Wyoming, he is kidding himself. He doesn’t need it. A .30/06 is adequate for 90 percent of all African hunting. So are any of the 7 mm. Magnums, the .280 Remington, the .270 Winchester, the .284 Winchester, or even the little 7 x 57.

This, I know, is going to drive the lovers of the big bores mad. The thought of anyone’s knocking off a large animal, particularly an African animal, with a fairly light bullet is almost more than they can bear. For many years some of them have sniped at the .270 because it is the most popular of the small-bore precision cartridges.

Read Next: The Coolest Old Jack O’Connor Photos from the Outdoor Life Archives

Bob Lee tells a good story. He was on safari in Kenya when his camp was visited by a well-known big-bore advocate, who was also on safari. He was looking over Bob’s battery when he spied a fine custom-made .270. Holding it at arm’s length with one hand as if it were an over-ripe fish and his nose with the thumb and forefinger with the other, he asked: “Bob, what in the hell are you going to do with this damned thing?”

“I’m going to shoot a lot of game with it,” he told him.

Read the full article here