Pork Rinds Are My Secret Weapon for Summer Bluegills

This story, “Living End for Bluegills,” appeared in the July 1965 issue of Outdoor Life.

WE KNEW THAT in the lake there were bluegills the size of pie plates. They had spawned six weeks ago, and at that time we had quickly put limits on our stringers when we fished for them in the reedy shallows. But now, in late July, it was hot in northern Michigan, and we knew the fish had scattered over the lake bottom and were deep and in groups. But where?

As Mike, my oldest son, put the canoe into the water, I noted with satisfaction that, at 13, he was as tall as his dad and strong. I liked that. He could do the work while I took my ease, but he was wise to me, of course.

“Don’t wear yourself out, pop,” he said while carrying our gear from the car.

I was equipping our spinning rods with a special bluegill rig. Slyly, I said, “Somebody has to do the headwork. I’m scheming to find the big ones.”

Soon I had our “secret weapons” ready. We placed ourselves comfortably in the canoe and paddled briskly for a few minutes until we were well out on the lake. Then we laid the paddles aside and let the light breeze move us gently across the water’s surface.

“It saves work,” I told Mike, “and sooner or later we’ll drift over a school. Then my strong medicine takes over down below, and we’ll either anchor and load up or catch them on the drift, paddle back, and repeat.”

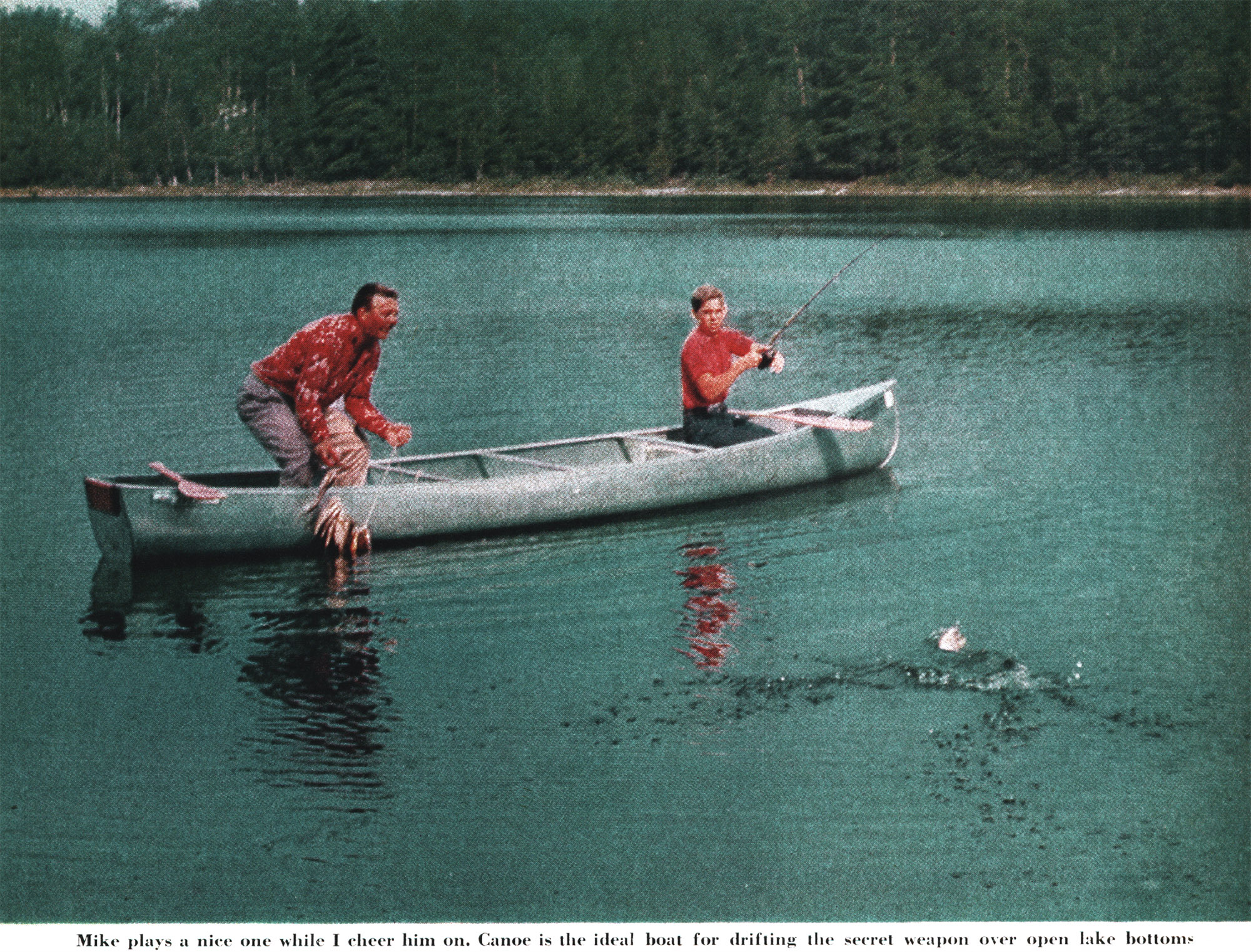

I handed Mike his outfit and picked up my own. We both cast into the breeze. The sinkers went down until they were on bottom. We could feel small bumps as they crept along. Then, with startling abruptness, Mike’s light rod snapped into a bow and he set the hook. “Got him,” he said.

At that instant I, too, got a good strike. There was no time to put our anchor over; we were busy. I have long claimed that a big bluegill puts a bass to shame with its stubborn battle, and these two were big. They cut circles, almost crossing our lines. Mine then ran off behind me and curved the rod tip around toward the canoe’s stern. Mike’s fish zinged off in the other direction, but at last we brought them in near the canoe where they spun in dizzying circles.

As they were lifted aboard, Mike’s shook free of the hook. “Go ahead,” I said, “catch another. I’ll string them.” They were beautiful, big fellows, handsomely colored, deep-bodied, and broad-backed. The lake is a favorite of mine. A friend and I once took an 11 ¾-inch male bluegill out of it that weighed 1 ¾ pounds. That’s unusual, of course, but we’ve often caught limits of fish that weighed a pound each.

Mike had another before I could get the first two strung. “I have to give you credit,” he said as he worked on the fish. “This rig really works.”

It does. It struck me as odd that here we were mopping up with it in northern Michigan, almost at the Canadian border. The first time I had tried the rig was on a lake within a few miles of the Mexican border. Paul Young, an auto dealer in Laredo, Texas, and I were after bass that day. He has a small lake formed by a dam on property he owns at the city’s edge. I was using a weedless spoon with a piece of white pork rind trailing it, a deadly combination for largemouths.

Paul was floating in a tube and using a fly rod.

“I don’t fool with all that contraption you’ve got,” he said. “For a long time now I’ve been fishing a pork rind on a thin wire hook — nothing else. It’s the finest ‘wet fly’ for bass ever invented. Maybe I invented it, too. I’m not sure. At any rate, I’ve never seen anyone else use it that way.”

I had to admit it was working. Paul had a bass dancing along the surface every time I looked around. I was doing fine, but he was hooking more fish per number of strikes than I was.

As we lazed on the bank at midmorning, I remarked that I was getting a lot of short strikes.

“Those aren’t short strikes from bass,” Paul said. “There are a lot of big bluegills in here. They grab the pork rind just as avidly as the bass, but they don’t often get hooked because the rind is too long. I’ll show you what to do about it.”

He used a No. 6, round-bend hook made of fine wire with a medium shank. The hook, he told me, straightens out and pulls free easily if you hang up in weeds or debris, yet it is strong enough for the fish and light enough for use with a fly rod. The hook is not obvious in the water and has excellent hooking qualities because it’s so thin and sharp, but you can unhook a fish easily. Paul tied the hook directly to the end of his leader and slipped on it an inch-long, slender tab of white pork rind.

“Most fishermen,” he said, “use these little rinds as an added teaser behind a small lure or a streamer fly, but I learned some time ago to use them as the lure.”

He waded out, cast, let the pork rind sink a moment, then retrieved very slowly. His lightweight rod heeled over, and he was fast to a miniature buzz saw. In half an hour, he dropped eight big bluegills into his canvas creel.

That was my introduction, and I was instantly and thoroughly sold. It may be that the idea has been tried elsewhere, but I don’t believe the rig is widely used. I’ve shown it to many fishermen and have yet to find one who already knew about it.

That summer I was in the Great Lakes area. On a day of great exasperation, I stumbled on what I now call my secret weapon for finding and catching bluegills when they are scattered and deep. The exasperation stemmed from the behavior of the fish. When they’re spawning, bluegills swarm into relatively small areas suitable for fanning beds near the shore. They hit furiously at this time, and it’s no problem to rack up big catches.

But once spawning is over and the nest-watching male has left the fry to fend for themselves, the adult fish seek deep water. It’s too warm for them in the shallows, and they scatter all over the bottom. The fish are thin and worn, and they begin to feed voraciously. They range over more open bottoms, but they find good forage by grubbing nymphs and other food from the sandy mud. For example, I’ve drifted success fully for plate-size bluegills right out across a Florida lake that had absolutely no vegetation on its bottom. Small and medium-size fish may still be in weeds, but the big ones aren’t.

On the day I discovered my secret weapon, I knew the fish would be in water from 10 to 25 feet deep, so I used spinning gear and tried various baits. I recalled one old bluegill fisherman telling me, “Sometimes they’ll just take crickets fished way down. Other times, they want a small redworm or a grass hopper.”

Possibly it was true, but I remembered how that small pork strip on a wire hook had mesmerized the fish in Texas. Why not set up a rig with the rind on a dropper to comb the bottom for them? The white pork rind would have top visibility at any depth, and I hoped its motion would be irresistible even when fished very slowly.

I looped a small bell sinker on the end of my line. A foot up the line, I tied an eight-inch loop and attached to it a small wire hook. Then I dug out a pork rind of fly-rod size and slipped it on. The sinker made casting easy, and quickly took the wriggling pork strip down to the bottom.

On that very first cast, way out in the middle of the lake, I felt the terminal rig pause. I thought I’d snagged a weed, and I raised up hard. Brother, did he ever go! The light line whizzed off at a tangent, and soon the big fellow was sizzling around at boatside. Since that day, the rig has been my most consistently successful setup. The pork rind is just as successful down deep with a sinker as it is when fished without one in the shallows.

That day in Michigan, as Mike brought his second fish in and complimented me on the pork-barrel rig, I picked up a paddle and gently shoved us back upwind for another float. As soon as I put the paddle down, I cast and let the lure sink. I had an instantaneous hit and missed the fish. I peeled a bit of line to let the lure drop back. The fish picked it up and I set into him.

I slipped the small anchor overboard, for Mike had one on too and I knew we were into a pocket of fish.

“We’re stopped now, “I told him. “Try to match your retrieve speed to what we were doing on the drift. It must be just right.”

He shook his fish off into the canoe and cast again without pausing to string it. He was in a big hurry- and I didn’t blame him. We could have been catching those bluegills by fishing a worm or half a night crawler in deep water, but worms are a lot messier than pork rind and you have to take time to bait up. With a tough rind, you can sometimes catch 50 without changing or losing your lure.

here’s another interesting angle here, too. With pork rind, you can usually unhook a bluegill easily, be cause they seldom swallow the rinds and are lip-hooked nine times out of 10. They gobble worms and often are gullet-hooked. Plastic worms in small sizes work fairly well, but they don’t have the toughness, action, and visibility white pork rind has.

Mike hooked a fish that went under the canoe and came up on the other side. But he finally brought it around, flopped it aboard, and cast out again. “You see,” I told Mike, “if we were still-fishing over the side with bait, we might drop anchor and scare the school.

Or we might try a lot of places and miss a school by yards. By drifting or anchoring and making long casts all around, we cover a lot of bottom and find the fish without disturbing them.” “I think the lure movement means a lot,” Mike said, and I agreed with him. You must cast and retrieve or drift to activate the pork rind. During their stay in deep water, big bluegills are not easy to catch. They’re wary and often don’t move much. They find a place with good forage or springs where oxygen is plentiful and stay there. A bait still-fished down to them may be investigated and turned down. But a moving lure with a lot of action such as pork rind provides teases them into pursuit if it doesn’t move too fast. Before the crafty old bluegill knows it, he’s aroused, follows the rind, pecks at it, and the thin, sharp hook does its job.

When we had a dozen fish on the stringer, we began freeing some.

We kept only the largest, and vied with each other to see who could get the heaviest fish or the most handsomely marked male. After a bit, I pulled anchor and we went drifting off to find another school. We hadn’t caught a single small bluegill.

This tended to substantiate my theory that the small, immature fish stay among the weeds in shallower water while large fish, frazzled during spawning, seek the depths to recuperate.

In scores of lakes where only small bluegills are caught, big ones could be taken if anglers fished deep. There are many large lakes all over the country that contain big bluegills, often unsuspected. Soon we struck fish again. I picked up the paddle and circled us around. The fish appeared to be spread over a fairly large area, because after we anchored we had hits no matter in which direction we cast. I had one fish that kept following and tapping at the pork rind for a long way before he finally banged it.

“Maybe he followed the trail,” I surmised.

We had a visitor at our home in Texas last year who is convinced fish follow scent trails through the water. That’s how they find a bait so quickly, he theorized.

“Fish like the smell, or taste — it may be all one to them — of salt,” this man told me. “A pork rind drawn through the water lays a scent trail that spreads out like a fan or cone. A fish can home right to it in a hurry, and I’m convinced that’s one reason why old fashioned pork rind is such a successful lure.”

Perhaps he’s right. At least, I can’t prove he isn’t, and certainly the theory backstops my secret weapon perfectly. I have another friend who likes to use a strip of chamois instead of pork rind, simply because he doesn’t have to keep it in a bottle of preservative. But I feel the rind is more effective because of the salty solution it is preserved in.

Because the day was hot and some of the fish on our stringer had died, we quit fishing and went ashore to clean them and put them in an ice chest.

After we’d eaten lunch, I put on my waders while Mike went out with the canoe to practice paddling. I knew of several stretches of shoreline where the bottom dropped off from a sandy, reedy edge. I could cast into deep water there and retrieve without the danger of get ting hung up.

When I picked up my rod, I found that my rind had been hanging high and dry and was shriveled and hard as bone. That’s one thing a rind user must remember-the rind must be kept moist. Once dry, it takes on a brownish cast and hardens.

The small fly-rod rinds were in the canoe, but in my tackle box I found a jar of long ones of bass size. It’s not always easy to find the small rinds in stores, because today’s anglers are pre dominantly spinning men and prefer the larger sizes. Many dealers don’t stock the small ones. I fished out a big rind and trimmed a piece for bluegills. When you do this, cut an inch-long V to fork the tail and trim the sides down some to keep the rind narrow and small. You can get several bluegill strips by cutting up one bass-size strip. But bluegill strips cut from bass strips, I’ve found, are not as good as the fly rod size. The longer strips are thicker, and when they are cut into shorter pieces they don’t have as much action as the thinner strips.

It took me a while to find the fish, but when I did I pulled in one that fought especially hard. It turned out to be a big common sunfish. As a rule, the common sunfish feeds over softer bottoms and closer to shore than the bluegill during the deep-water period, but they are just as susceptible to pork rind. In Montana last summer, I strung them by the dozens. It’s not generally known that common sunfish range that far west, mainly because the lakes they inhabit out there are trout lakes.

By the time Mike came ashore, I had several bluegills and big sunfish. I peeled off my waders and got back into the canoe. The breeze had come up a bit, and we paddled across the lake to the lee shore, just close enough to drift away nicely.

“I think the wind’s just right to drift us along outside the lily pads in deep water,” Mike said. “Ought to be a good place.”

He was right. A drop-off gives the fish a chance to feed on a slanted bank which is always rich in nymphs and small worms. We gently coaxed the canoe around so it would move broadside with only an occasional paddle stroke. About 50 yards downshore, we hit the fish again.

“This must be the granddaddy,” I said when one really slammed me. My rod was down over the side of the canoe, and then the line started moving up in the water on a long slant.

“You’ve got a bass,” Mike said. “He’s going to jump.”

He did. I guessed he’d go three pounds, but he threw the hook on the first jump. That was fine with me. It was bluegills we wanted. Right away, Mike had another bass, possibly weighing a pound. He boated it and dropped it back.

“Let’s move,” he said.

We paddled out into the lake again. Incidentally, a canoa is excellent for our kind of bluegill fishing. It takes almost no effort to move and there is no splashing of oars. Only the lightest of anchors is needed to hold a canoe, and when it drifts it slides along at proper speed and can be turned into the wind to slow it down.

The breeze had shifted enough so that I figured it would take us back across the lake almost right to our car. “Let’s fish it out to the other shore and quit, shall we?” I suggested.

“We better quit,” Mike answered, eying the stringer somewhat skittishly. “It’ll take you an hour to clean them.” “Me!” I roared. “You’re mixed up, bub. I wouldn’t rob you of the opportunity to learn to do it as expertly as your old man.”

The banter ended abruptly with two well-bent rods. We worked the fish in, let them go, and cast again. In a moment we were hooked up again.

“Just think,” I said to Mike, “how many bluegill fishermen never get this kind of action because they stick tight to the weeds and stay off the open, deep bottoms.”

Then, when I glanced across the lake toward the shore, I got what I thought was a bright idea.

“When I was your age,” I said, “I could have grabbed a paddle and shot this canoe across to the car in five minutes flat.”

“Haw,” he blurted out, “watch this.” I relaxed and watched the beautiful string of bluegills trailing alongside. What fine sport, I thought, and what a wonderful age for a boy when his old man can con him into doing the work. But that won’t last long.

Read the full article here