Old-School Tips for Catching Giant Bass in Small Ponds

This story was originally published in the June 1966 issue of Outdoor Life. During the 1950s and 60s, the author, Anthony A. Ciuffa absolutely hammered giant largemouth bass in small farm ponds across the Midwest. From April to November he fished at least twice a day, every day —— for 10 years. He’d typically catch more than 125 “big bass” (fish weighing more than 7 pounds) annually. Here’s how he did it and what he learned.

The bass fishing year can be divided into three seasons, and each calls for its own lures and methods. At all times, however, water temperature and light intensity greatly affect the willingness of bass to strike.

Spring is the best season of all. Fall, though not quite as good, is still better than the hot weeks of midsummer. Most of the bass I have caught of four pounds or over have been taken between mid-April and mid-June, the last two weeks in September, October, and the first half of November if conditions are right.

The bulk of my bass fishing the past 10 years has been done in the small waters of St. Louis County, Missouri, and April is the best month of the year to take tackle-busters there. As water temperatures rise in early spring, the metabolism or life processes of bass also perk up. They need food to keep pace with their increasing activities, and because they have not yet shaken off their winter stupor completely they are far more easily fooled then than later on.

When early spring winds start moving a lake surface, a piling up of surface water takes place at the side toward which the wind is blowing. This forces deeper water to flow toward the side from which the wind is coming, and in this way the denser and colder bottom water is gradually circulated to the surface, where the wind warms and aerates it.

As this process continues, the entire lake, unless it is very deep, reaches a point where the temperature at the surface and bottom is the same. As the sun becomes warmer, during periods when the wind does not blow enough to maintain circulation the surface temperature climbs and the water there becomes more buoyant. At this point, circulation continues only in the warmer layer, and stratification takes place.

With the first sign of the warming undercurrents, bass, which congregate in the deeper waters of a lake in winter, move toward shore. During the cold months their life processes have slowed down, they have become very sluggish and, in northern waters, close to dormant. Though they stir out with the return of spring, they have little interest in prowling the entire lake. Instead, they move to the nearest shoreline, usually a steep bank or dam with deep water just offshore, where warm currents can hike their metabolic rate.

In the warmer water, egg development soon begins in the females and they must take food abundantly, even though they are still in a foggy state. A similar process soon follows in the males, and there is no better time in the entire year to take advantage of both. That’s the period for catching trophy fish, before they scatter to spawn.

The most favorable water temperature for tempting a lunker (most of them will be females) that is going through this early buildup is between 55 and 60 degrees. So when you find your favorite lake almost completely turned over, with deep water close to shore that reads at least 55 degrees at the surface and the same 10 feet down, start hunting blockbusters. And when the water edges up to 58 degrees at those same levels, fish as often as you can.

Even if a cold spell follows warm weather, if the temperature has already been stabilized at 58 to 60 degrees those same steep banks and dams on the downwind shore are spots to bet on.

In early April of 1965, I went fishing on a small lake near Hannibal, Missouri. The water was 58 degrees at the top and the same 10 or 15 feet down, but the day was overcast and cold, and a hard wind was blowing out of the northwest. I chose a dual lure, a spinner above a leadhead, the latter trailed with a yellow-and-black rubber skirt. I added a white pork-rind eel, first cutting off about one inch to take care of short strikes, which are common at that time of year.

Read Next: The Best Bass Lures, Tested and Reviewed

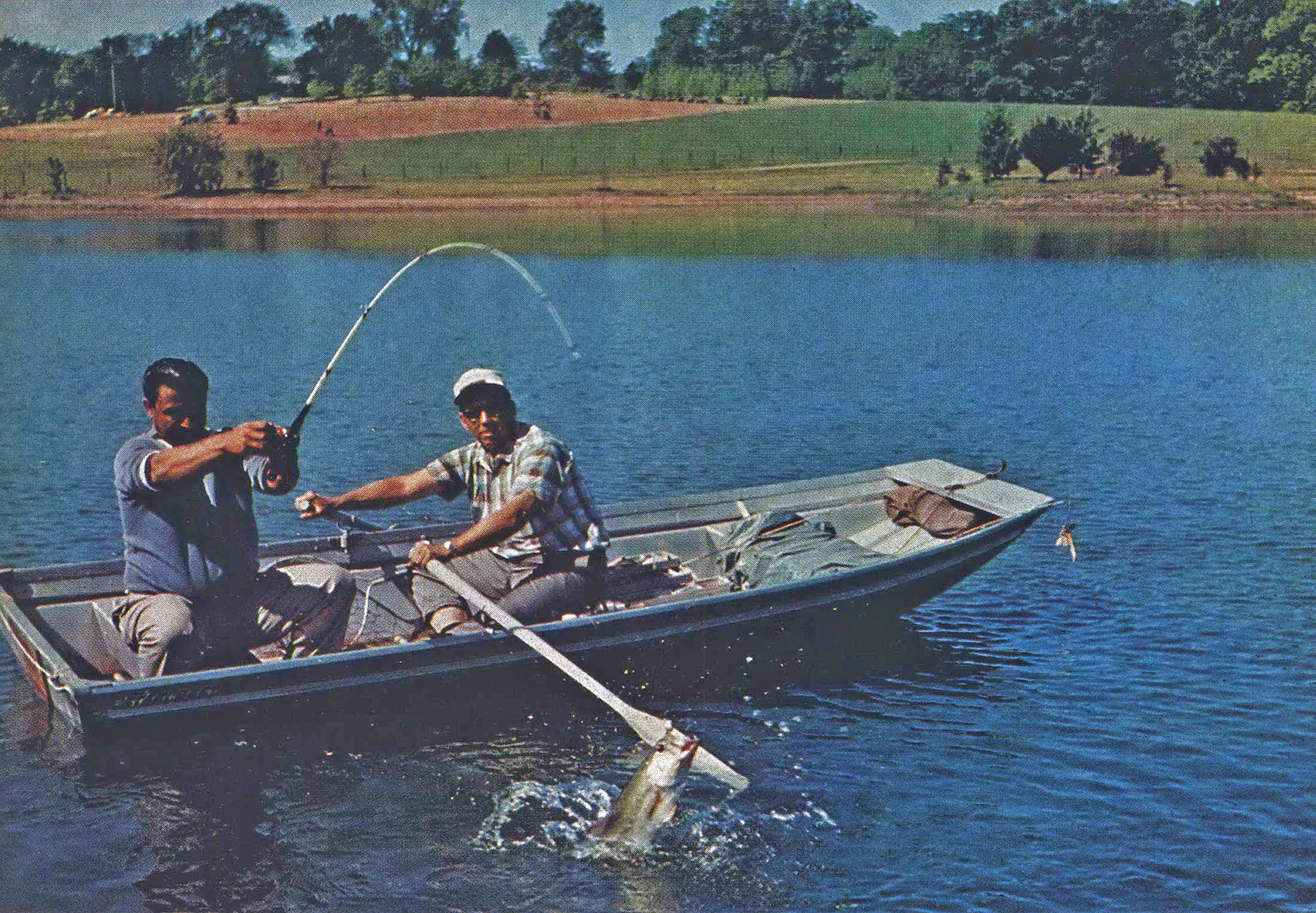

It took half an hour to get my first strike, casting parallel to shore and working the lure close to bottom about 10 to 15 feet out. The fish was a seven-pound female, heavy with eggs, that took the lure five feet down. I didn’t want to alert any other bass in the neighborhood, and I had 20-pound-test line, which I use when I’m expecting fish of that size, so I horsed her in. About 45 minutes later, in spite of hands stiff with cold, I hooked another only 40 feet from the same spot. It was also a female, 5½ pounds. Fifteen minutes later I landed a two-pounder, which I released immediately.

At 4:30 p.m., two hours after I started fishing, I hung a third female that scaled 6½ pounds. I photographed the three lunkers, put two of them back, and started home with the seven-pounder. In my pond-bass fishing I make it a rule to keep nothing smaller than that.

A week later, Ken Rauth, a St. Louis construction superintendent who fishes with me often, and I decided to give that same lake a whirl. The wind was warm from the southwest, the sun was out, and it was a beautiful spring day. But we agreed that the great increase in light intensity would cut down our chances, and we were right.

We fished until almost dark, using various spinner, eel, and pork-frog combinations, dragging them through snags, fishing vertical banks, using every trick we could think of. Our total catch was two bass, one 10 inches, the other 12.

“You should never have let those two big ones go last week,” Ken grumbled. “I can see them, down there on the bottom, conducting classes in how to avoid rubber skirts, pork eels, and silver spinners, telling the little ones, ‘That’s the way to live to a ripe old age.’ You ought to know better.”

But just at dark Ken got a walloping strike and landed an eight-pounder, and an hour later I came up with a six-pound bass. The decreased light intensity that came with nightfall had set them to feeding.

I rate lure color to be very important. Early spring bass like white or yellow, and spinners help greatly to get the attention of fish in early morning, evening, and on cloudy days. If the sun is shining and the water clear, my favorite spring lures are a pork frog on either a weighted weedless hook or a leadhead. Of the two, the weedless hook is easier to work and less likely to snag. I often use a leadhead with a light weed guard to keep the tails of the pork frog hanging on the hooks.

When the springtime water is dingy, or in cloudy weather and morning and evening fishing, I find spinner lures best, used in combination with a yellow or white pork-rind eel, yellow plastic eel, or pork frog.

All of these should be allowed to settle almost to the bottom before the retrieve is begun. I retrieve spinner baits at a medium pace. Using a leadhead and pork frog, I make it hop in short pulls or use a steady medium-speed retrieve that will make the frog’s tail wiggle, stopping occasionally to let the lure sink, then starting it again. The pork frog on a weighted weedless hook should be retrieved at slow to medium speed, parallel to a steep bank and three to six feet out. That’s where a live frog would be, especially just before dawn or from sundown to dark.

Another effective trick is to let such a lure settle on the bottom in five to 10 feet of water, then crawl it slowly over submerged brush, stumps, and other cover. All of these methods are terrific with pork eels as well as frogs, too.

Incidentally, it’s important to keep pork-rind baits in fresh brine. Otherwise they become rancid, and bass may not hold on long enough for you to set the hook. Best of all, I like to soak them in brine laced with 10 percent Italian anisette. Bass find that flavor hard to resist.

The food needs of a bass are almost certainly as great in summer as in spring, but by that time he has settled down where groceries are abundant ( he does that shortly after spawning) and your bait is likely to get to him when he is stuffed with natural food.

When water temperatures reach 70 to 75 degrees on the bottom at five to eight feet, bass can be found all over a lake, but the best places are in water about eight feet deep if the day is sunny, and along shorelines near that depth in cloudy weather or before and after sunrise and sunset.

Though light-colored lures are deadly in spring, black, blue, and red are better in summer, probably for reasons connected both with light intensity and the increased wariness of the fish. When water temperature 10 feet down is above 70 degrees, my favorite combinations are a black plastic eel or blue or black pork eel, on a red-and-brown hair jig with a ¼-ounce leadhead. Although black eels and worms are good any time the water reaches 65 degrees, they’re best of all when it’s above 70 degrees.

With this warmer water, however, keep an eye on clarity. If the water is murky, I try a spinner bait and red pork eel on one rod, and a red eel on an orange hair jig or plain leadhead on a second rod.

If the water is reasonably clear and has reached 65 to 75 degrees 10 feet down, I like a black plastic eel on a leadhead on one rod, and a red pork eel on a bucktail jig with black-and-orange hair on another. The purpose of using two rods is to switch every few minutes until you decide which lure they pref er. At such times, I also test a spinner and leadhead trailed with a black rubber skirt. In very clear water, especially on bright days in early spring, I use this with the spinner painted black.

I make my own black spinners by sandpapering the blades and painting them with a nonhardening automobile gasket compound that won’t chip off. I find these black blades very effective at night all through the summer, too.

Another great summer rig is a black plastic eel or worm on a plain leadhead. Apply rod varnish to the hook and shank before threading the soft lure on and allow it to dry overnight, to cement the eel or worm in place. In the case of the plastic eel, trim the tail to a slim taper. When a bass picks it up and feels little to hold onto, he’ll bite ahead and give you the signals you need to tell you when to set the hook. Plastic worms are slim enough so that no tailoring is necessary.

All my experience indicates that bass never seem to get wise to a black eel on a leadhead, bounced rhythmically off the bottom or retrieved close to bottom with an up and down swimming motion.

A black worm is about as good. I recall a trip my two boys and I made one July several years ago to a heavily fished public lake 30 miles west of St. Louis. The sun was burning in a cloudless morning sky and it looked as if we had picked the worst possible time, but we had a trick up our sleeves in the form of black plastic worms on home-made ¼-ounce leadheads.

I had found out that making up those leadheads, melting the lead and pouring it into molds around the hooks, was a fine father-and-son project. We often made as many as 60 or 70 in an evening, sealing the worms on with rod varnish, to take care of a fantastically high rate of snagging.

We had plenty along that hot summer morning and we worked them close to bottom, alongside sunken trees and through brush. We hung up often, but in that kind of fishing if you don’t catch snags you don’t catch fish. Within three hours we had taken nine bass, none over five pounds but none under two.

In daylight, a black worm or eel seems to have an edge over blue. At night the two are about equal, and red is also very good. But once summer comes, the white and yellow eels that caught big ones earlier are likely to get you only small fish. The one and two-pounders can see what they’re striking, but they don’t have the caution of granddad.

On bright sunny days in summer, look for a shady place where light intensity is reduced. Try casting under a boat dock, but only if the water is at least eight feet deep and the dock free of traffic. Also fish near trees or on the shady side of a deep cove. Going into deeper water is another good way to take lunkers at such times.

And, of course, night fishing comes into its own when summer arrives. Most fishermen like nights with some moonlight, but I suspect the moon is more important to them than to the bass. I’ve taken s01ne good lunkers on moonless nights, and unless I can find water deeper than 20 feet I count a quarter moon better than a full one.

A good nighttime lure which has taken some fine bass for me, when the water is above 65 degrees 10 feet down, is a blue pork-rind eel on a 3/0 weighted weedless hook crawled very, very slowly on the bottom parallel to a dam and 10 to 15 feet down. Give the reel handle a slow turn, pause, then another slow turn, so the eel crawls with a natural motion.

When water temperatures climb above 78 degrees, big bass are usually found near dams or in the deeper parts of ponds and small lakes. In the dusk of evening, they may move in close to shore to feed, even right up against shore, but only where the bank is steep and they can make a rush for deeper water if danger threatens.

Quiet and careful fishing becomes all-important if you hope to take lunkers from small waters in summer. Don’t get too close to the places where you think big ones may be hanging out, no nearer than is absolutely necessary, and move very quietly.

I have said nothing so far about topwater lures, maybe because most of my fishing is done with eels, pork frogs, spinners, and other lures that go deep. Surface plugs will get you nowhere when the lake is too cold for top-water activity or when bass are deep in the heat of summer. But there is a period, roughly May and June where I fish, when they are deadly if used right. They seem to get in their best licks during spawning season, and after spawning until the surf ace water exceeds 80 degrees. At such times, a top-water lure may take more fish than any other.

One of my fishing partners, Chuck Novak, and I went out before daylight one morning last May and started fishing with pork-rind frogs and black eels on black-and-orang_e jigs, that being what water temperature and other conditions indicated. In two hours, we had seven or eight strikes from heavy bass but didn’t hook a fish. They were striking short.

“They need something that will make ’em sore enough to take a good bite,” Chuck said finally, “and with a hook on the tail end, too.”

He changed to a top-water plug with a weighted tail and began the thrashing retrieve that we rely on with that lure. On the third cast, a four-pound bass followed the bait almost to the boat, slapped at it two or three times, then grabbed the tail hook and bit down. I followed Chuck’s example, and when the bass quit striking at 10:30 that morning we had netted nine that ran from two to 4 ½ pounds, and we had so many more good strikes that we lost count.

Though May and June are the prime months for top-water plugs where I fish, and they lose their effectiveness as the water warms, there is a period again in July when they make a good showing on pond bass, but only in very early morning or when the sun has dropped over the horizon, and for a while after dark. At any time they are more likely to take two-pounders than lunkers. Big bass prefer to rustle their grub on the bottom, whether in three or 25 feet of water.

When fall arrives and water temperatures begin to drop, bass feed with greater abandon again, though with far more caution than in early spring, I suspect partly because they have learned from their summer experiences and from seeing other fish caught around them. But October is almost always an ace lunker month for me.

The biggest pond bass I ever caught, an eight-pound 10-ounce fish (my record was a 9½-pounder landed in Lake Ouachita, Arkansas, in 1960), was taken on a moonless night in October, 1964, from a seven-acre lake in the western outskirts of St. Louis.

I was using a blue pork-rind eel on a weighted weedless hook. That’s my favorite combination for fall fishing, once the water has dropped below 65 degrees. Another good bet is the spinner baits mentioned for spring fishing. The eel calls for the slowest possible retrieve, dragging the hook at snail’s pace through brush, over submerged trees, and into all sorts of places where big bass forage.

That night the blue eel seemed irresistible. I got strikes from bass of all sizes. Finally, fishing near a dam in 10 feet of water, I felt two light tugs. I lifted the rod tip gently and could feel something hanging on. An instant later, there came three or four more tugs. They were not the light tappings of a small bass, but good solid pulls. I took in all the slack and let him have it. He fought hard and I realized I had hooked a real tackle smasher.

My favorite all-around line is 15-pound-test, but when I have brush to contend with and know I may have to turn a big one in a hurry, I prefer 20- pound, which was what I was using that night. Even so, I let Mr. Big work off steam for a long time before I brought him to the net. There’s power in a bass of that size.

Winter brings pond-bass fishing to a standstill. Falling water temperatures force the fish into deep water, and once it drops below 48 degrees they become almost dormant, feeding only infrequently. The same thing is true of bass in big lakes, but since they congregate in deep places in great numbers the right lure has a better chance of encountering one that is ready to feed.

At any season, weather exerts a strong influence on bass behavior. From spring to fall, one of the best times to take them is just before a storm, when wind and lightning are bearing down. There seems to be something about light intensity at such times that puts them to feeding.

I recall one such evening when my sons, Robert and Richard, and I were on a lake in the August Busch Wildlife Area near Weldon Spring. We fished for hours without taking a bass. Then a violent thunderstorm came up, and in 10 minutes, before rain began to pelt down, Bob took two five-pounders and Rich landed one of 3 ½.

Read Next: Right Before We Shipped Out to the Front Lines of WWII, a Local Took Us Bass Fishing

Next to a day when a storm front is approaching, the second best time to go bass fishing, assuming water temperatures are favorable, is when the sky is completely overcast to cut down light intensity and enough wind is blowing to ripple the water, especially if it’s blowing toward a steep shoreline of a pond.

Finally, the best day of all is any time you can go out. The more often you fish and the more time you spend at it, the better your chances. And don’t forget that the bass you return to the water will be there next time, bigger and better. Leaving a population of catchable bass in small lakes and ponds is the key to many hours of future enjoyment.

Read the full article here