My Mountain Goat Fell Off a Cliff. We Went After Him — and Got Trapped

This story, “Bad Day on Goat Mountain,” appeared in the July 1985 issue of Outdoor Life.

He who hesitates is lost, the old saying goes. I hesitated and my guide and I were almost lost for good.

Had I pulled the trigger — two seconds sooner, there would have been no problem.

We could have skinned out a fine trophy goat in warm sunlight and had a pleasant stroll down the mountain. But that two-second delay pretty much ruined my day.

It started out as a fine morning in British Columbia.

The mountain air, kissed by frost then warmed by the rising sun was like a clear, dry wine. Birch trees, shedding their summer burdens, showered the still earth and fast waters with golden doubloons. The horses stamped and snorted jets of steaming air, eager to go to the mountain, and when I climbed into the saddle, the pancakes and bacon felt just right in my belly. It would be a good ride, eight or 10 miles, to the mountain where the big goats were.

I was hunting out of Coyne Callison’s main camp on the Turnagain River in one of the best big-game areas in North America. Within easy walking distance of Callison’s comfortable log cabins, there are plenty of Stone sheep, moose, goats, black bears, and grizzlies. Because the populations are steadily expanding — especially the number of grizzlies — not only are there plenty of these animals, but there are many trophies, as well. Every season, Callison’s hunters take game that qualify for the Boone and Crockett record book. I expect that there just might be a world-record Canadian moose loafing around there somewhere. In 1983, one of Callison’s clients took the No. 2 moose. I saw three big grizzlies in two days and lost count of the moose.

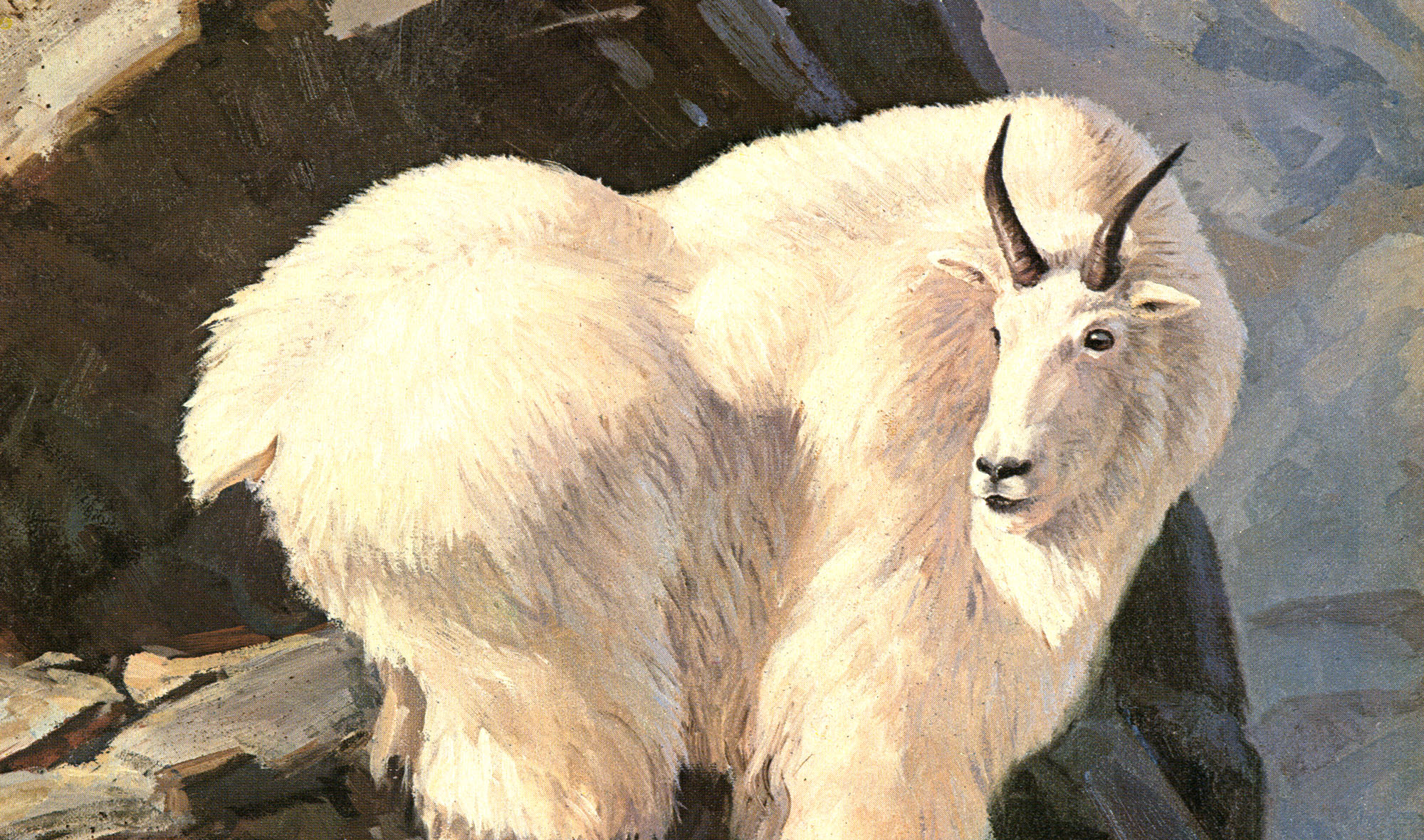

My hunting pals were outfitter Jack Atcheson and Bob Funk, the boy wonder of the oil industry. Atcheson books most of my big-game hunts and we have come to be known as the rainbow boys because of our incredible luck when we hunt together. After arriving in Callison’s camp via floatplane from Watson Lake in the Yukon, we split up. Jack and Bob went to separate spike camps for moose and sheep. I was after a big billy goat first and foremost, but I also had tags for moose and grizzly. To my notion, the North American mountain goat is one of the world’s most underrated game animals. Not underrated, perhaps, so much as ignored. One has only to look at the places where goats live to decide that there are easier things to hunt. Yet a big billy is one of the most magnificent trophies that this continent offers. He survives, not by killing his enemies, but by luring them to places where they kill themselves. His siren call is the wind and his weapon the mountain.

My guide was Claude Smarch, a savvy young fellow who learned the business from his dad. Claude had been after a particularly big billy all season but hadn’t been able to get a hunter within range. The goat had a lookout position near the peak of his mountain fortress that gave him a view of most approach routes. That made him all but impossible to stalk.

A big billy is one of the most magnificent trophies that this continent offers. He survives, not by killing his enemies, but by luring them to places where they kill themselves. His siren call is the wind and his weapon the mountain.

But it was a great day to hunt goat and I was feeling lucky, a feeling that blossomed when Claude and I arrived at the foot of the mountain and hid our horses in a willow thicket. Far above, the old billy was in his favorite lookout spot but hadn’t noticed our arrival. We had sneaked in through a back door of our own. If he stayed put for the next few hours, we had a chance of climbing the mountain undetected.

The mountain was steep and tall, but I’ve been on worse. Anyway, a mountain is al ways easier to climb when there is game at the top. A few weeks earlier, while making a movie for Remington Arms, I had hurt my knees so that walking was a bit painful, especially when angling around hillsides. For this reason, I found it less painful to climb straight up than to follow the usual switchback climbing pattern. The result was that, even with a bum leg, I’ve never climbed faster. By late morning, we were near the peak and had begun creeping around it to the bench where we had last seen the goat.

Everything seemed perfect, and it almost was. We calculated that we were about 50 to 70 yards above the goat’s lookout spot, which was a narrow bench. By simply circling around the mountaintop and not making any serious mistakes – such as causing a rockslide — we hoped to put ourselves almost on top of the wary old billy.

But something always seems to go wrong when the setup is too perfect. The old goat wasn’t where he was supposed to be, which meant that either he had high-tailed it over the crest while we were on the blind side of the mountain or he had simply moved one way or the other along the bench. From our position, we could only see a few yards of the bench so, after a whispered planning session, Claude and I separated. We worked our opposite ways around the mountain.

We had been separated only a few minutes when I heard a pebble land at my heels and turned to see Claude motioning for me to head back. He had spotted the billy, he whispered, lying behind a boulder at a narrow part of the bench. To get a clear shot, I’d have to cross a steep shale face. I’d be in easy view of the goat if he looked up and, if I kicked a single stone loose, it would surely spook him. We were already within 75 yards of the billy.

Despite the short range, I wouldn’t get a clear shot until I was even closer because of the convex curvature of the open shale face. As I worked my way closer, planning each step with breathless care, I could see the goat’s horns and head but nothing more. Finally, after spending 10 minutes crossing less than 20 yards, I settled into a sitting position behind a rock outcropping. The goat was too close to miss. How could anything go wrong? After pinching the rifle’s safety lever off between my fingers so that it wouldn’t make a sound, I steadied the crosshairs on the goat’s backbone. At the downhill angle, steeper than 45°, the 250-grain Nosier bullet from my .338 Winchester Magnum would sever the backbone and drive on into lungs and heart.

All I had to do was press the trigger, but I hesitated. The reason for my delay was that the goat was lying down. I once had a foolproof shot at an antelope that was lying down and missed it clean. I never did figure out why I missed except that I might have been fooled by the angle. An animal in its bed can be a deceptive target. Besides, I just don’t like to shoot them that way. So I waited. Soon the goat would be on his feet and I’d have a fair shot.

If the animal moved a few steps either way, he would be out of sight. Worst of all, if he went over the edge of the bench, he would fall more than 1,000 feet into a deep ravine.

Claude, I knew, wanted me to kill the goat in its bed, and for good reason. If the animal moved a few steps either way, he would be out of sight. Worst of all, if he went over the edge of the bench, he would fall more than 1,000 feet into a deep ravine. Many good trophies have been badly damaged by long falls, and some have been lost forever. Still, I held my fire because, when an animal gets up, even if it’s spooked, it will usually stand still for a moment, determining the source of danger and deciding which way to run. I’ve spooked deer and elk and other game out of their beds and always had ample time to shoot.

The goat had already sensed that something was wrong and would soon be up. He was moving his head in quick jerks, trying to see everywhere. That gave me a good look at his horns, shining black and hooked at the tips like Arab daggers. If the horns of a Rocky Mountain goat measure nine inches or more, he is a really good one. I estimated the old billy’s horns at 9 1/2 inches and had a vision of his head on my trophy-room wall when suddenly he pivoted his head around and looked straight at me. He was running even before he was fully on his feet — toward the cliff!

My bullet caught him just as he dived over the edge and tumbled into space. He was dead in midair, no question about that. Claude and I both saw a bright red spot high on his shoulder.

When I climbed down to the bench and looked over the edge, I could only hope that the goat hadn’t fallen far and had been stopped by a tree snag or boulder. No such luck. As far down as we could see, there was nothing. My goat was somewhere far below in a deep ravine.

“OK, Claude,” I said, trying to sound optimistic, “this is what you’re getting paid for. Let’s go find him.”

“It’s a long way down there,” he answered, trying to match my optimism with a half-hearted grin, “but one thing’s for sure. When we find him, he’ll be half skinned.”

It was a long way down, but that didn’t worry me half as much as the fact that it would also be a long way back up. As far as I could see, there was no way out of the black ravine except to climb out. The morning’s hike up the mountain seemed like a cakewalk compared to what lay ahead.

While Claude took a more or less direct route, deliberately sliding and falling on the loose shale, I followed a slower course, looking for a way to come back up. In places, the steep mountainside gave way to vertical rock walls and I had to make long detours, stopping to look back to make certain that I could find a climbable route out.

Though the day had been pleasantly warm, it was cold and dark in the ravine. Great sheets of ice clung to the rock walls. Apparently, the sun never penetrated that lonely place.

“Over here!” Claude shouted from my right. “He’s wedged behind a rock.”

“Can you climb back up from where you are?” I shouted back.

“No way. It’s too steep over here. I’ll have to keep going down.”

“Wait until I get below you,” I yelled. “Then roll the goat on down.”

Not far below, a torrent of water surged through the ravine. I wanted to be where I could grab the carcass before it could be swept away by the current and lost forever.

With each step, the ravine became colder and darker. Above me, the crest of the mountain gleamed in the sunlight. It seemed very far away. The stream bed was a jumble of boulders that tortured the water into a roaring cataract. After finding a place where I had fairly good footing, I shouted for Claude to let the goat slide on down. Moments later, there was a crashing from above, a shower of loose dirt and rocks around me, and the goat splashed down.

While Claude caped the animal, I backtracked up the mountain a ways, wanting to make sure that we had a way out. I’d briefly considered following the stream out of the ravine but abandoned the idea. Every few yards, the water plunged over a precipice and fell several feet. The falls that I could see could be negotiated without trouble, but it was the falls I couldn’t see that bothered me. What if we got into a place where the drop was too steep and too deep to go down and too high or slippery to go back up? It would be a bad place to be stranded. A misstep on an icy rock could mean a broken leg, and then what?

“What are you doing up there?” Claude yelled when I was 50 yards above him, looking for my original trail.

“We’ve got to go back up this way,” I answered. “We might get trapped in the ravine if we follow the stream.”

“Don’t worry,” he answered, surprised at my concern. “If we follow the stream, we’ll be out in an hour. If we climb back the way we came, we won’t be back to camp before dark. Besides, it’s safer this way than trying to climb up that loose rock.”

The first few waterfalls were no more than five or six feet high and could be climbed if we had to backtrack. But as we went farther downstream, the stream squeezed be tween vertical walls and the falls became higher and higher. That’s when we came to the place that I had dreaded, and I heard it even before I saw it. The water crashed down for 10 feet and then exploded into spray that froze on the rock walls.

“If we go down there, we won’t be able to climb back up,” I told Claude.

“Don’t worry, we won’t want to come back this way, anyhow. We’ll soon be out,” he replied.

Claude went first, hanging on to my hand and then dropping another five feet to the rock stream bed.

“Come on,” he urged. “It’s not bad at all.”

I tossed our meat-laden backpacks down, then the goat’s head and hide and my prized David Miller rifle.

Rolling over on my belly and sliding off a rock shelf at the side of the falls, I inched down until my feet touched Claude’s shoulders. I was safe.

“There’s nothing to it,” Claude told me.

I was nearly convinced until we rounded a sharp bend and peered over the edge of the next waterfall. It was more than 20 feet to the bottom and there was no way to climb around it. The rock walls on both sides were straight up and down and were covered with ice. There was no way out but down, and that meant a long drop. It also meant that we’d land in the water below. And how deep was it? Was it deep enough to cushion our fall or did the foaming water cover solid, bone-breaking rock?

The chances of surviving without serious injury, I calculated, were perhaps three in 10. Not very good odds. If both of us were injured or knocked unconscious, our chances of survival were next to nothing. Who would look for us in that dark ravine?

To drop into deep water was too much of a risk. The shock of the freezing water would be bad enough. But the alternative, landing on hidden rock, was even worse. The chances of surviving without serious injury, I calculated, were perhaps three in 10. Not very good odds. If both of us were injured or knocked unconscious, our chances of survival were next to nothing. Who would look for us in that dark ravine?

The only hope was to go back upstream and try to climb the other waterfall. But was that possible? We went back and tried to get a handhold or foothold on the slick rock, but it was no use. Just as I had feared, there was no way to climb out. We were trapped.

Claude and I both knew that we were in one hell of a fix, but we never admitted it.

“Let’s take a break,” I suggested. “There’s no use in burning up our energy. After we get a rest, we’ll figure this out.”

Mentally, I went over the equipment that I carried in my daypack. I had about five feet of nylon cord that was strong enough to hold a man’s weight. What else? My rifle sling — that was four more feet! Could we tie together enough sling and cord and strips of clothes to let ourselves down? Sure! We’d make it out of the hole after all.

Wet and cold maybe, but at least in one piece. While I was putting my ideas together, Claude was doing some thinking of his own.

“If that log were a few feet longer, we could use it like a ladder,” he said, pointing to a bleached length of spruce wedged between some boulders.

“It’s long enough!” I shouted. “Let’s prop it alongside the waterfalls.”

“But it’s too short,” Claude protested. “It’s no more than 10 feet long. Even with the log leaned up on the ravine wall we still have over 10 feet to fall.”

“We’ll tie my rifle sling to some cord I have and loop it around a rock at the top of the fall. Then we can let ourselves down to the log and shinny down the rest of the way.”

After tying the cord to the leather sling, we looped it around the stub of a limb at one end of the spruce log and swung it into position. This was accomplished by lying on the edge of the waterfall, half in the current, and stretching my arms until they ached. Claude held on to my legs to keep me from being washed over the edge. After a couple of tries — and almost dropping the log once — I leaned it against the wall at an angle that I hoped would hold. Next, we tied a loop around a rock at the edge of the shelf. This left about five feet of cord and sling to hold onto, with another five or six feet to the top of the nearly vertical log.

Claude went first, wriggling off the edge of the rock shelf and letting himself down slowly. When his boots found a hold on the log, he waited a moment to catch his breath, then let go of the sling. For a moment, he teetered in midair and then, ever so carefully, he bent his knees until he could grab the top of the log with his hands. He easily slid down the thin log and landed safely on solid rock in the shallow water.

Next, I tossed the packs and hide down and, holding my breath, let the rifle fall. Claude caught it easily.

“You next, Jim,” he said with a grin. “It’s as easy as rolling off a log.”

“That’s not funny,” I answered.

The tough leather sling felt strong in my grip as I inched off the shelf and let myself slide down the icy rock. I didn’t look down or up. I stared at my bare hands gripping the leather.

“How close am I?”

“Just a few more inches. Keep coming.”

Then one boot touched the log and it felt good to shift my weight to my legs. After that, it was like going down a ladder and I stood beside Claude, looking up at the sheer wall of ice-covered rock. It seemed impossible.

“That’s a good sling up there Claude,” I said. “If you ever come by this way again, be sure to get it for me.”

“If you don’t mind,” he answered, “I’ll just buy you a new one.”

Read Next: Carmichel in the Middle East: Risking Our Lives to Hunt Iranian Ibex

I guess that rifle sling is still there, dangling from a short length of nylon cord in a deep, dark ravine where the sun has never shined.

Read the full article here