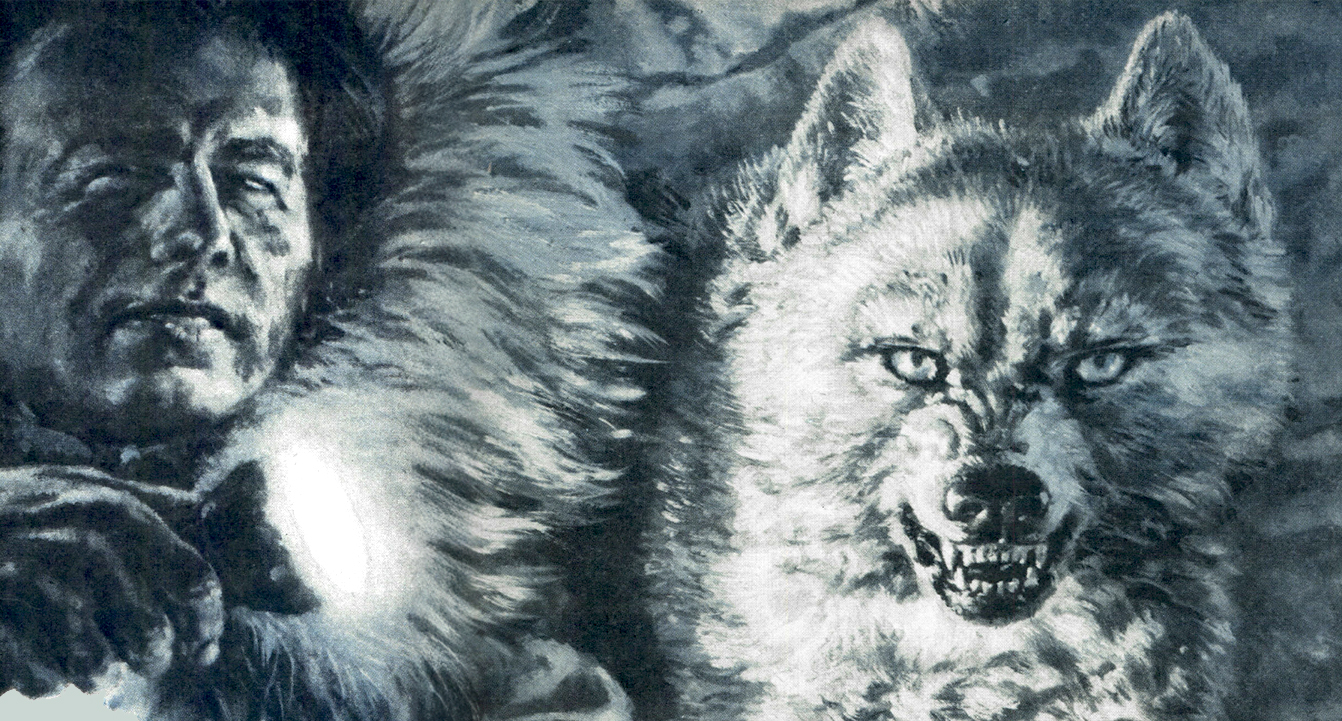

My Best Sled Dog Tangled with Polar Bears, Hunted Birds, and Saved My Life More Times Than I Can Count

This story, “Snow Dog,” appeared in the March 1950 issue of Outdoor Life.

No doubt about it, it was the worst storm of the winter — a furious, deadly mating of fifty-mile winds and fifty-below-zero cold. It had driven me to cover hours before, and now I lay huddled in my caribou-skin sleeping bag listening to the gale as it raged and ripped against the frail snow house.

The time crept slowly toward midnight. Then there came a lull in the storm, and I began to relax. But only for a moment. The great white husky dog at my side suddenly bounded to his feet and growled a deep and menacing challenge.

I clawed out of the sleeping bag, like a man trying to escape from a straitjacket, and fumbled frantically in the dark. When my numbed fingers finally closed on the flashlight, its weak beams caught the white dog standing tensely, legs trembling violently; against the low, rounded ceiling the bristling guard hairs of his shoulders cast enormous, shimmering shadows.

It was January, darkest and worst of all the Arctic months. We were on a low spit of land extending into Kotzebue Sound, an arm of the Arctic Ocean on the northwestern Alaskan coast. Fully eight hours had passed since the snowburdened cyclone had roared down upon us, a Niagara of powdery whiteness and screeching blasts that literally tore the breath from a man’s mouth. Even the sled dogs, tough as any animal can be, huddled before the seething wind and started to dig themselves into the drifts. That was when I decided I’d better follow their example.

Now, in the yellow rays of the flashlight, I studied the white leader, Jack Frost. His growl, the alertness in his strange blue eyes, told me that some menace was impending. Then his lips curled back to expose the white, glistening teeth. Almost automatically, I reached out and drew my rifle from its sealskin case.

Was it a polar bear? We were in white-bear country. When the blizzard smote us in the dusk of early afternoon I’d been mushing my string of fifteen Siberian huskies across a neck of land well known among the Eskimos as a crossing p lace for polar bears. I was pushing hard to reach a deserted sod igloo a few miles down the coast. The screaming, wailing snowfall had stopped all that. There was but one thing left to do: turn the loaded sled on its side, drive the iron brakes deep into the hard-packed drifts, and start to build a snow-block ice house. It wasn’t an easy job. I was dangerously stupefied by cold before I had finished the hollow half-sphere of porous snow. But there were still chores to be done before I could crawl into its shelter.

To each dog I tossed a nightly ration of dried salmon and blubber, and they came shaking themselves out of their snow burrows to seize the food before the wind ripped it away. From the sled I took sleeping bag, grub box, and primus stove, and dragged the load through an opening in the snow house. Then, followed by Jack Frost-the white leader who always shared such hardy comforts as the winter trail afforded — I crawled inside and plugged the opening behind me with a snow block saved for the purpose. I got the primus stove going, and in a few moments the constricted chamber became fairly comfortable. It started out to be just another night on the tundra — and then came the tense warning of the white leader.

Now he growled again, then barked savagely. Outside, I heard the other huskies take up the outcry. And as they did I became aware of a faint rumbling, a sound that grew from a mere vibration to the swelling rumble of drums. I knew then the terror that was descending upon us — a stampede of a great reindeer herd!

By now, my whole team had joined with the screeching storm to produce a hysterical, blood-chilling chorus. Against it grew the thunderous roar of hoof beats, coming closer and closer. For one breathless moment the vibrating snow house seemed about to collapse. Then, all at once, it was over. The vibrations faded, and there was only the wind thudding and shoving against the snow house.

Death had brushed by, with only yards to spare. Once again, my white leader’s uncanny alertness and intelligence had roused the other dogs. The stampeding reindeer-terrified perhaps by marauding wolves-had been turned almost at the last moment by the wild clamor of my team. Splendid Alaska Hunting It was all over now. Yet there was to be no sleep for me the rest of that long night. Half in the sleeping bag, shoulders protected by my sik-sik-puk parka, I lifted the primus stove out of its wooden case and touched it off. When the flame turned blue-green, I scooped a pot of snow off the ceiling and made a cup of coffee. Jack Frost crept close and shoved a cold nose into my hand to remind me that whenever I ate, he also got his share. I looked down on this remarkable dog who had saved my life on more than one occasion (and was to do it again). As I fed him a pilot biscuit my mind raced back to the day when I had lifted him from his mother’s breast and cuddled his white, woolly body in the palms of my two hands. That meeting had been a fateful one for both of us. Out of it had grown thousands of adventurous miles over the silent white spaces of northern Alaska. Out of it had come thrills and dangers, and an understanding between dog and man that I never would have believed possible if it had not happened to me.

Nome in the early ’20’s was a great place for a fellow who liked fishing and hunting and roaming in far-away places, which explains, in part anyway, why I was there doing special reconnaissance work for the old U. S. Biological Survey. Life was zestful, exciting. In July, you could pick your own brand of outdoor sports. You could tangle with a 3,000- pound walrus, or a shaggy white bear that was as likely to attack as to run away, or a puffing pygmy whale. Seals of many kinds, as well as countless eider ducks, swarmed the berg-studded Bering Sea, whose gray-green waters lapped on the Nome beach. You could walk inland and find yourself among clamorous nesting birds-cranes, ducks, snipe, and curlew. You could hear the boisterous cackle of the willow ptarmigan as it strutted on the tundra. Plenty of daylight for hunting, too: the sun, glowing like a polished copper disk, merely dipped into the Bering Sea at midnight, then rose and began another twenty-four-hour circuit of the skies. You could start out on a fishing trip any time you took a notion. That’s what I was doing when good luck brought me to the pup, Jack Frost.

From the village of Nome a narrow-gauge railroad led eighty miles back through the foothills and snow-capped Sawtooth Mountains to a long-deserted mining camp. The tram had once played a big part in the hell-roaring days of early Nome, but now its light rails were frost-twisted and askew. Only a dog team could follow its weird curves. I had fashioned a “pupmobile” from an abandoned railroad handcar, and used it to keep my sled dogs in summer training and to indulge in what was probably the best fly fishing in America. That was how I came to pick up Jack Frost — I had a date with a fresh run of Dolly Varden trout and some Arctic grayling.

Beside me on the seat of the old handcar that day was another pup — the first snow-white, blue-eyed Siberian dog I’d ever seen. A renegade trapper had smuggled it across the Bering Sea and I had swapped a pair of binoculars for it. When I lifted the dog chariot off the tracks that day at Robber’s Gulch, I had no idea that I was to blunder onto a perfect mate for this fluffy little female.

I was knee-deep in the Nome River floating a Gray Hackle when I noticed a hairy character standing by the pupmobile. A bright, silvery Dolly Varden struck at that moment and I was busy for a spell. Finally, I slipped a net under its red-spotted side and carried the fish ashore. Then I recognized Jake Tupelo, an old-timer who lived up the track a short distance. He was staring bug-eyed at the little white pup.

Harry Quits Civilization

“By Godfrey!” he exploded. “Didn’t think no one could do it. Didn’t think Hollerin’ Harry’d sell that pup ever. How in Tophet did ye get it?”

“I didn’t. That pup came straight from Siberia. I got it in a swap in Nome.”

Jake scratched his wild mop of hair. “Don’t that beat all?” he said. “Danged if Hollerin’ Harry ain’t got the very match of that little critter. Must be the only two pure snow dogs in the country. Now, if this’n happens to be a bitch … “

“It does,” I cut in. Ideas began spinning around in my head. I leaned the fish rod against the willows. “Wish me luck Jake,” I said, “because I’m on my way up to see Hollering Harry!”

Harry was not the kind of a man you visit whenever you took a notion to. He didn’t live up on the edge of Robber’s Gulch because he liked people. A certain weakness — or a pair of them — had made Hollering Harry one of the oddest characters in the Nome country.

To begin with, Harry had a voice like the bull of Bashan. There was no taming it. You could hear him from one end of Nome to the other when he was in mild conversation, and when he got excited you plugged up your eardrums until you could get away. Secondly, Harry was extremely sensitive in a certain portion of his anatomy. He’d leap like a stricken gazelle if anyone so much as touched him from behind. These two traits had made a violent kind of hermit out of Hollering Harry. On his rare visits to town some practical joker was always sure to prod him in the rear with a thumb, whereupon Hollering Harry would fetch a yell like a steamer whistle and leap a couple of feet high.

On his last trip to Nome, harassed Harry had tried to slip quietly into the Board of Trade Saloon for a quick pick-up before heading back into the hills. Someone had touched him off from behind and Hollering Harry had responded by climbing over the bar, spilling bottles and glasses, pulling down the fixtures, and letting go with a stentorian shout that brought out the firemen. When they got there they found Hollering Harry embroiled in a fist fight with an innocent party, while the joker who started it all egged him on from the side lines.

Hollering Harry thereupon vowed that he would never come to town as long as he lived. He said he’d stay out there in the hills with his dogs, and that the next man who got behind him would wind up full of bird shot.

This, then, was the character I was going to see. I figured that Harry would be so intrigued by the sight of another pure-white pup that he would hold his shotgun fire. I spotted him shoveling dirt into a sluice box, but his back was toward me, so I waited until he turned around and saw me, still some distance away.

Even so, he jumped as though he’d been stung by a bee when he saw the little white Siberian in my arms.

“Where did ye git that pup?” he roared, and down in the river bottom, where I had them staked in the willows, my dogs rose to their feet in alarm.

Carefully avoiding any abrupt movement, and keeping well in front of Harry, I approached until he could clearly see that this was not his pup. “It’s a female,” I told him.

Hollering Harry motioned me toward his tar-paper shack. Several of his Siberian huskies were staked along the path. They were beauties, mostly grays and mixed black-and-whites, deep-chested and short-coupled, with springy backs and smooth, trim legs. It was about the finest stock I had seen in Alaska. But there wasn’t an all-white dog in the string.

A Deal for the Pup

I took a seat on the edge of a wooden bunk where Hollering Harry could keep me in sight. He came in behind me and on his way reached behind the cast-iron heater and pulled a suckling pup from its mother. He set it on the floor, and I placed mine beside it. Neither of us spoke for a minute as we watched the handsome pair, but I knew that I would have to own them both. Hollering Harry gazed in awe at the only perfectly matched, solid-white, blue-eyed Siberians ever brought together on our side of the Bering Sea.

“Name yer figger!” he said, in what evidently was meant to be a friendly tone, but which sent my little female scuttling under the bunk. I noticed, though, that the male held his head up bold as a lion as though he thought that was the way all humans talked.

“Name any reasonable figger!” repeated Hollering Harry.

No use letting this go on, I thought; might as well come to the point. “I’m not selling,” I said. “I came up here to buy your pup. You name a price.”

Harry looked at me with utter scorn. Then he bent over the bunk, and his arm muscles stood out like whipcords as he hefted a pair of buckskin pokes up onto the table.

“I don’t need money!” he roared. “If I did, there’s more where this come from! I want that bitch pup! How much?”

I got up and carried my pup to the door, still being careful not to get behind Hollering Harry. When I was well in the clear, I played my trump card.

“So long,” I said, “I’ll be seeing you in town!”

Hollering Harry’s eyes snapped fire. “You’ll have an almighty long wait if ye do,” he sounded off in his loudest voice. “I need grub right now, but I’ll never go near the place.”

And that is why I was able to buy the suckling white pup, Jack Frost. For the next two years I freighted out loads of groceries and mail to Hollering Harry’s place in Robber’s Gulch. I also paid him a stiff fee, and he made me promise him a choice of the first litter produced by the two white huskies. It was the biggest price I ever paid for a sled dog. But it was also the best bargain I ever made, and Hollering Harry knew it. Every time I hove into view with a sack of groceries on my shoulder, he would greet me with abusive roars.

Not that I blamed him. From the very first Jack Frost was something special. In addition to all the remarkable traits that have been bred into most Siberian huskies in more than five centuries of severe selection on the blistering cold steppes of northern Asia, Jack Frost had certain extras that come only once in hundreds of pups. He had endurance beyond any ability of mine to properly test — once he led my team twenty-two hours without rest or food — and his intelligence was greater than any I have ever noted in any other breed. He had an effortless, bounding gait that sent him flying over the drifted snow like a tumbleweed across a Dakota prairie. Work? He’d rather pull a dog sled than eat, and he traveled faster at the end of the day than in the morning. He was clean — immaculate in his habits, and he was polite to strangers.

During his first fall, when he was still a rollicking youngster, Jack Frost followed me through the waist-high willows in search of ptarmigan. He had a nose as keen as a fox’s and a natural interest in finding game. Often his curled white plume wagged eagerly and his low whine sounded before I knew there were any birds near. When a covey of ptarmigan exploded out of the brown willows he would yip-yip sharply as though to urge me into action. Now, I’m not claiming that Jack Frost was the equal of a trained bird dog. Even so, he was exceedingly tender-mouthed; he’d retrieve game all day without mussing a feather.

From the very first, Jack Frost let me know that he was no ordinary sled dog. He seemed to feel that his place was at the head of the team, and no apprenticeship period back in the string, please. He knew the commands, of course. With a light rope around his neck I had taught him to turn slightly to the right at a mild command of “Gee!” and to swing at right angles at the same word uttered sharply. At “Come Gee!” he was to swing completely around to the right in a U turn. The words “Haw!” and “Come haw!” did it for the left side. “Whoa!” meant to come to a full stop, and the words “Mush!” or “All right!” were the green light to go ahead. Jack knew all these commands at the age of six months, but he still had something to learn. He thought he was a leader until his first lesson with the older dogs in the team. That took the ego out of him in a hurry. For fifty feet he stayed ahead by pouring every ounce of his awkward energy into the drive. Then his puppy legs buckled and he went down under the flying feet of his mates.

Jack Frost Moves Around

For the next month or two he was content to play along as “loose leader,” running ahead of the team unhitched as long as he could, then falling to either side or behind when the pace got too fast. In this way his strength developed rapidly. He gained his natural weight of just under sixty pounds, and at times he put on brief bursts of speed that marked him as a great future racing dog. Through his off-trail scamperings he often traveled twice as far as the rest of the dogs in a day’s journey. It was all fine training for a coming leader.

In those days, a man could gallop up and down the mail trails all winter without too much risk, but when he pushed off into the trackless spaces he was asking for trouble. Generally he found it. The people who do most of the talking about a friendly Arctic seem to thrive even better in the lobbies of our best hotels. I have traveled for eight days over white desolation without seeing anything bigger than a chickadee. Chickadees are friendly enough, but you can’t live on them.

Fate of a Show-off

In the years when snowshoe rabbits were at the peak of their cycle, it would be fairly simple to gather food for yourself and the dogs. Sometimes all you had to do was stop the team at the first patch of willow and scrub spruce, walk through it with a .22 rifle, and come staggering back under a load of bunnies. At other times you might find a flock of ptarmigan budding in the bush tops and lay into them as fast as you could pull the trigger of your shotgun. Freshly killed, or frozen to flinty hardness, this small game was polished off by the huskies in short order — heads, feet, fur or feathers, bones, claws, and toenails. You couldn’t even find a pink spot on the snow when they were through.

Once we were short of rations in the Koyukuk plateaus, and neither rabbits, grouse or ptarmigan could be found. Then a herd of caribou suddenly showed like pinpoints on a distant hill, but they spotted the team and sped out of sight before I could jerk the rifle out of its scabbard. What followed was a sort of minor miracle. One of those foolish caribou decided he’d show us how fast he could travel. Leaving the rest of the herd, this dim-witted creature circled to our rear, then started overhauling us in mile-eating strides. Head in the air, big feet flying, the lone caribou drew abreast of the team, hung there for a moment while it looked us over disdainfully, then pulled the throttle another notch and, with lofty arrogance, cut in ahead of the team and went bounding away over the tundra, the team in pursuit.

Never have I seen dogs or caribou travel so fast. Aiming a rifle from the careening sled was like trying to shoot from a roller coaster. Straight ahead, its tail stiff as a ramrod over its rump, the whizzing caribou presented a violently jumping target. I missed four times, but connected dead center with the next shot. We lived three days on that addle-brained beast.

In his fifth year Jack Frost was the leader of a dog team that aroused the envy of every musher we met on the trail. He had his mate, Snowflake, at his flanks — and every dog in the string was one of their pups! Every last one of them was pure white, and all but one was blue-eyed. When I delivered another load of groceries to Hollering Harry his indignant yells could be heard at sea. Even so, he wanted to hear all about the exploits of the team on the trail in far places. And when I bragged about the races they had won and their all-round excellence — as dog owners will — why, he just sat and beamed with satisfaction. Harry was a misanthrope, but not when it came to dogs.

He’d got me into one helluva situation, but he had got me out, too, so we were even.

It was shortly after this visit to Robber’s Gulch that the white team and I had an experience that came near being our last. I was making a short cut from Kotzebue to Cape Espenberg on a perfect spring day, and it took us ten miles out on the frozen Arctic Ocean. There was not a cloud in the sky and the temperature, about 10 below zero, was just right for fast traveling. We could save two days of hard mushing around the beach line by four good hours of travel on the over-sea ice. There would have been nothing to it, if it hadn’t been for that pesky young polar bear.

It was rough sledding out there a dozen or so miles from shore. On all sides were giant ice slabs turned on edge from pressure of the salt water. In between there were narrow, open leads of green water where glistening seal heads bobbed.

With plenty of fat, blubbery smells in the air the huskies became greatly excited. I was riding the brake almost continually to hold down the speed of the sled enough to make numerous jackknife turns through the jumbled ice pack. And then, as Jack Frost led the team around a corner ahead of me, he stood straight up on his hind feet and let go with a demoniac howl! In a flash the team was out of control. All I could do was hang on grimly, mitted hands glued to the handlebars, as the sled turned on its side, skidded for a distance, turned completely upside down, and finally bounced back on its runners — all at top speed.

Drifting Out to Sea

When I finally got a look ahead I spotted the polar bear, a yearling of not more than 300 pounds. Nanook wanted no part of the ravening pack behind him, and was shuffling across the ice in high gear. There was only one thing to do to end the canine hysteria, and I did it. I yanked the rifle loose and stretched him across the ice.

It was a fine hide, and I thought the meat could be put to plenty of use. So I hog-dressed the bear on the spot and rolled it onto the sled.

Then we were ready to proceed on our journey. But, to my horror, I found we had no place to go. We had chased the bear onto an ice floe, which now had become completely separated from the shore ice! We were on a floating island. It was the kind of a set-up that had taken the lives of many Eskimos, and one that I had always guarded against. Adrift on an ice floe — a favorite way of making widows in the Nome country!

After the first shock had worn off a little, I noticed that the drifting floe was in a slow spin as it moved out toward a grinding ice pack. And then I saw that one point of the island was going to swing very close to the main ice field on the next revolution. It offered a gambler’s chance and I decided to take it. There was no future in riding that floe ice; it would certainly be chewed to pieces when it got into the heavy current.

I had the team lined up for what seemed like an eternity along the point of ice, waiting for it to swing by the main field for the last time. I learned how easily you can sweat while standing still at 10 below zero. Then the point of my island came around and I yelled, “All right, Jack!”

It could have been the end. It could have been a watery grave for all of us. It all depended on Jack Frost leaping across and dragging his team mates behind him with no slackening of speed. I heard him whine softly at my command. Then he started off down the narrow point at breakneck velocity and launched himself into the air. He seemed to hang there over the black water — and then he was streaking away on the other side. It was fully eight feet across, but I have only the haziest impression of riding the sled over the deadly space. It seemed fairly to scoot across, with its bow hitting the far ice before the runners under my feet left the floating pan.

When the danger was past I stopped the huskies, walked up to Jack Frost and twisted his ears in the way that he loved. He’d got me into one helluva situation, but he had got me out, too, so we were even.

Read Next: The 10 Best Dangerous Game Cartridges

Some seasons you might travel the entire length of the coast without seeing a polar bear. Other winters they seemed to be all over the place. It all depended on ice conditions. This was one of their big years. We hadn’t traveled more than twenty miles when we ran into an Eskimo trapper skinning a tremendous beast on the beach. It was as big as a horse. The Eskimo told me that the bear was feeding on a frozen walrus carcass and that he had walked up within thirty feet before shooting it with a .25/20 rifle. I made a proper salaam to the courage of a man who would tackle a beast of that size with a peashooter at ten yards, and mushed on my way.

Hardly had we passed out of sight when a movement out on the ice fields drew my attention. It was still another polar bear. It had spotted my team and appeared to be stalking it. Maybe he liked white dogs. On a fast shuffle the bear headed for the beach some distance ahead, a good spot to intercept the team. Fortunately, none of the dogs saw the bear, for their attention was centered on a playful white fox up ahead. It jumped from behind an ice hummock, swished down the trail, hid behind another ice hummock, and so on, until the excited dogs were moving that sled as fast as it ever had traveled. By the time the little Arctic fox tired of his game, the polar bear was far behind. That suited me fine. I was becoming slightly allergic to them.

Ole Has a Nasty Visitor

Even so, I saw still another before reaching Nome on that trip. But first I had to hear all about it from a Scandinavian character named Ole Tokkelson. (Practically everyone in Alaska in those days was a character.)

Ole, a former Nome panhandler, was trying his luck at fox trapping in the seldom-traveled Cape Woolley region, about seventy miles north of town. Several weeks before he had mooched a ride out and holed up alone in a deserted sod igloo. The only firearm Ole possessed was a .22 caliber pistol. He had no dogs. His trapline extended up and down the beach as far as he could travel in a short day. He hadn’t seen another human for two months when I came along, and was down to seal meat, beans, pilot biscuit, and tea. He was the wildest-looking individual I had run across in many a day. To make things worse, his snuff had given out a few days earlier. And to cap the climax, he’d had a visitor the night before — a big, burly polar with larceny in his heart and homicide in his eye.

“He smell me, he did,” said Ole, his frightened blue eyes as big as billiard balls. I could understand that — I smelled him too.

We squatted in the foul gloom of the igloo while Ole pointed out a broken window in the top, so close you could stand and stick half your arm out in the wind. The window pane, of stretched walrus gut, had been pushed in. Ole explained:

“He coom by and he smell me. He quick smash a hole wit’ his foot. He look down and he see me.”

The opening, cut through two feet of granite-hard sod, was scarcely a foot in diameter. Obviously, no bear could get through it. So I waited for Ole to explain.

In the first place, said Ole, he was afraid to shoot the .22 pistol for fear it would only make the bear madder. So he cowered back in the igloo when the beast reached down with its big white paw and started feeling around. Somehow, by crowding back against the wall and then on the dirt floor, Ole managed to dodge the big claws.

“By golly,” said Ole, “dat bear got mad. He stick his eyes down da hole and he see me again. And now he call me names. He pull back his eyes, he roll up his sleeve, and he reach way down again. All ay can do is keep on yoomping around. At last, he go ‘way.

“What color is polar bear nose and tongue?” continued Ole. “Ay tell you. It is black. What color his teet’? Ay tell you too. It is yellow. Maybe before night is over you see same thing, but ay hope not.”

Ole rattled on like a machine gun. Jack Frost, who had been curled quietly at my feet, suddenly sniffed the air and let out a sharp bark. Instantly, the huskies outside took up the hue and cry. Ole and I crawled out through the long, narrow, entrance tunnel. Jack, crowding behind, leaped quickly past us and raced down the beach. In the blue-white moon rays, we saw him trot confidently up to a big, ugly-looking polar bear. And then, to our surprise, the hulking white beast swung aside and lumbered straight away across the vast ice fields.

Probably this was the first dog the bear had ever seen. Did some strange instinct tell the white monster that the husky was an obnoxious little beastie to be avoided at all times? And did some atavistic urge tell Jack Frost that here was a big palooka he could lick? Well, there was a time, back in the dawn of history, when dogs traveled in yowling packs, pursuing and overpowering their prey through sheer numbers. Dog or wolf — there wasn’t much difference in those days.

Once, during the February mating moon of the gray wolves, I stumbled into a blood-chilling experience that seemed to indicate that the old kinship hasn’t entirely disappeared. It was deep in the mountains of the interior, in a wooded valley off the Yukon where many moose congregated during the heavy snows. It proved an arduous trip, because soft snow had forced me to snowshoe all day ahead of the team. A prospector’s log cabin on the bank, with smoke curling from the stovepipe, was a welcome sight at dusk.

With the usual hospitality of the north woods, Jim Hendryx came out on the bank to beckon me up the steep slope from the valley bottom. Then he led the team into a mine tunnel, where they’d have shelter for the night. He seemed desperately anxious for human company — worried and nervous, though for a while he made no mention of the cause. Nor did I ask any questions. In his own time and in his own way I knew he would tell me all he wanted me to know.

Jim dished up the beans and braised rabbit, and filled my mug with strong black coffee. “That white leader of yours had his hackles raised when he came up the bank. Do you know why?”

Call of the Timber Wolves

Now that Jim had mentioned it, I recalled that Jack Frost had been a bundle of nerves all afternoon. So had the other huskies. Several times they had broken out in noisy family squabbles — rare occurrences among Siberians.

The full moon rose over the rugged peaks to bathe the valley with cold, silvery light. After awhile, an eerie, high-pitched howl lifted tremulously into the sky and hung there, filling the valley brimful with wild, weird music. It fairly lifted the hairs on the back of my neck.

“It’s not your dogs,” declared Jim. “Not yet. It’s the biggest band of wolves ever to hit this valley. The gray devils have about cleaned up the moose, and still they won’t leave …. ” He stopped abruptly, then added: “Listen! Now your dogs have joined in. They’re all singing the same song.”

We stood in the open doorway while the white huskies sent their howls out through the open tunnel to blend with those of the timber wolves. Not one of the latter could be seen, though they were everywhere around the log cabin.

“They won’t leave,” repeated Jim. “They’re going to mate and den up for their pups right here in my valley.”

We trudged out to the tunnel with water for the dogs. Their dried salmon rations lay untouched on the floor. Their eyes glowed with excitement. They were under a spell cast down upon them through the ages. Countless generations of civilization, of companionship with man, fell away. Now the dogs knew only the age-old call of the wild.

That night with Jim Hendryx, and his valley of wolves, stands out vividly in my memory, much more than any of the hundreds of times my dog team and I bivouacked under the winter skies of Alaska. And there’s not much left now but those memories. The airplane has made the dog team a curiosity rather than a necessity — relegating it to small, odd jobs. There are no more of those sweeping trips across the entire length of that vast territory. Now and then, there’s a race in Fairbanks or Nome, true, but the sled dog as a vital cog in the life of the north is no more.

It’s like I was telling Jack Frost the last time we sat down together and shared a strip of dried salmon. He and I had both retired from the trails. Most of them were snowed-in from disuse and the old log cabins fallen to decay. We were a couple of has-beens talking it over.

Read Next: The Wolf-Dog That Called in a Pack of Wolves for Frank Glaser

“You know, old fellow,” I said to Jack Frost as I twitched his left ear, the ear he loved to have pulled, “the airplanes had to come and I’m glad they did. But there’s one thing they can’t take away from us. We got here first.”

The snow-white husky looked at me through those odd blue eyes that never registered fear. He poked me smartly with his paw.

“Pass the salmon,” said Jack Frost.

Read the full article here