Jack O’Connor’s Opinion of the Indestructible .30-06

This story was originally published in the November 1962 issue of Outdoor Life.

The .30/06 is the most popular big-game cartridge for bolt-action rifles in the United States and probably in the world. I have no figures from foreign factories, but I think it is reasonable to guess that more sporting rifles in .30/06 are made in Belgium, Finland, Sweden, England, and other rifle-manufacturing countries than rifles in any other caliber. I have seen .30/06 rifles of exotic manufacture in Africa, India, Iran, Mexico, and Britain.

Cartridges for the .30/06 are loaded wherever centerfire metallic ammunition is manufactured for sporting use in England, Belgium, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, and, I believe, Mexico.

The cartridge has gone by various names. An early one in this country was .30 U.S. Government, to differentiate it from the .30/40 Krag which was called the .30 U. S. Army. These similar names stamped on rifles made in the early years of this century have caused a good deal of confusion. Both the .30/40 and the .30/06 were used by the U.S. Army and were manufactured by the U.S. Government.

In Britain the cartridge was often called the .300 Springfield, and in Germany the 7.6 U.S., or, to use its full continental designation, the 7.62 x 62. The 7.62 is for the caliber and the 62 for the case length.

The name .30/06 came about because the cartridge is the .30 caliber U. S. military cartridge adopted in 1906. When we had our little war with Spain over Cuba in 1898, we Americans used the .30/40 cartridge in the Krag rifle. The Krag loaded one cartridge at a time into a box magazine on the right of the stock. Velocity of its 220-gr. bullet was about 1,900 feet per second.

The American military came home from the war with a great deal of respect for the Model 1893 Spanish Mauser rifle, which was loaded with five cartridges at a time from a clip, and for the 7 x 57mm Mauser cartridge, which gave a 175-gr. bullet a velocity of about 2,300.

So our ordnance people designed a pseudo-Mauser rifle, which came to be known as the 1903 Springfield, and a sort of magnified 7×57 cartridge to shoot in it. The cartridge was the .30/03-or U. S. military cartridge, caliber .30, Model 1903. It used a 220-grain bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2,350. However, it was found that with the powder then available, a charge sufficient to give that velocity produced rapid erosion and short barrel life. The charge was cut to drop the velocity to 2,200.

The 1903 rifle was generally called the New Springfield to show it was different from the old Model 1873 singleshot trapdoor Springfield. It was supposed to be an improved Mauser but the improvements were open to question. The action does not handle escaping gas nearly as well as the Mauser; the two-piece firing pin is much more liable to breakage than the one-piece Mauser job, and the coned breech of the Springfield barrel does not support the head of the cartridge as well as does that of the Mauser, which surrounds the brass case right up to the extractor groove.

The army had just settled down to enjoy the new rifle and cartridge when the German ordnance people brought out the Model 1905 version of their Model 88, 8 x 57 military cartridge. The Germans changed the diameter of their bullet from .318 to .323, lightened it from 236 grains to 154 grains, and changed its shape from round nose to spitzer, or sharp point. Velocity took a tremendous jump from 2,200 to 2,800 fps. The trajectory was flatter and the resulting danger zone much greater.

This left American ordnance with an obsolescent cartridge, so it was decided to see what could be done. The solution was to shorten the neck of the 1903 .30 caliber cartridge about 1/10 in. and to load the case with a 150-gr. sharppoint ( spitzer) bullet to 2,700 fps. All 1903 rifles in service were brought back to the arsenals. The 24-in. barrels were cut off one thread at the breech and the rifles rechambered. Since that day, the 24-inch barrel on the 1903 has actually measured 23.79 inches.

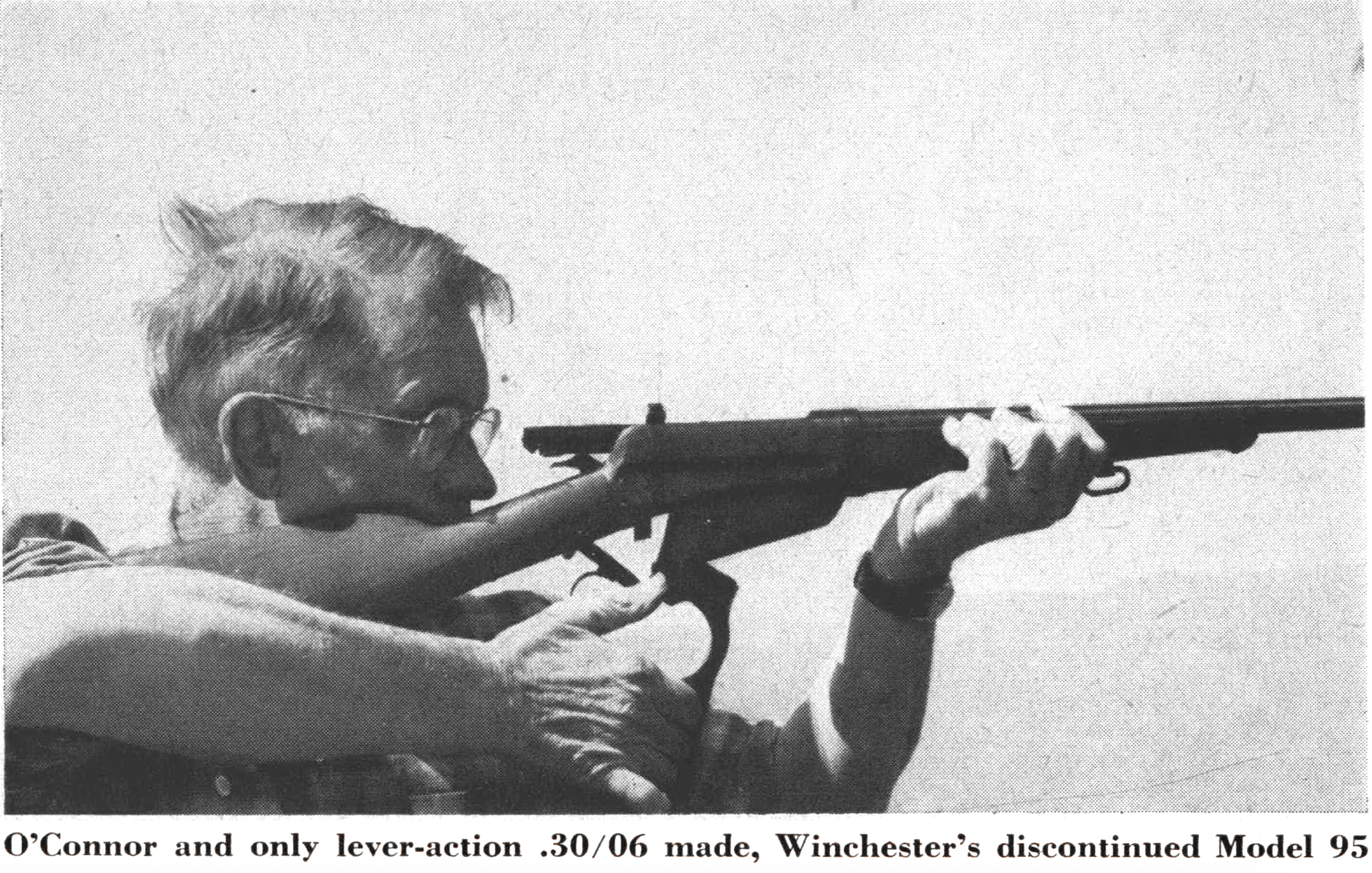

Inadvertently, this emergency revision of the 1903 cartridge made a very versatile job out of it. To give the proper length, the 150-gr. bullet had to be seated pretty far out. The result was that bullets weighing up to the original 220-gr. could be loaded in the long neck without the base of the bullet invading the powder space — a minor ballistic crime. Outside of the shorter neck of the case, the 1903 and 1906 are alike, with the same body length, shoulder angle, and body taper. As a result, 1906 ammunition could be used in 1903 chambers, but not 1903 ammunition in 1906 chambers. For some years, Winchester made the Model 1895 lever-action rifles ( the first factory big-game rifles for the new government cartridges) with both the 1903 and the 1906 chambers, and ammunition in both versions was made. The 1903 cartridge was always loaded with a 220-gr. bullet and the 1906 sporting ammunition generally with a 150-gr. bullet. When J.A. McGuire, founder and first editor of OUTDOOR LIFE, made a hunt in the Yukon about 1917, he took Model 95 Winchesters in both calibers — the 1906 for sheep, the 1903 for grizzlies and moose.

The Model 1903 rifle for the .30/06 cartridge had not been out long when sportsmen began to get interested in it for big game. Theodore Roosevelt took a somewhat remodeled .30/06 military Springfield with him to Africa in 1910. Early hunters used the regular 150-gr. spitzer bullet for big game. It was unstable, because it was short and had a sharp point. Often, but not always, it would tumble when it struck flesh and inflict a terrible wound. Sometimes, however, it would go straight through without tumbling; the result was a small hole and wounded game.

American loading companies quickly brought out sporting ammunition, but many of those early .30/06 bullets were real turkeys, as no one had enough experience with high velocity to know how to make good bullets. Most of those of lighter weight had jackets too thin and lead too soft and did not penetrate properly on the heavier animals. About 30 years ago, however, good bullets started coming along — the 150 and 180-gr. Western open-point boattail, the 150-gr. and 180-gr. Winchester pointed soft-point expanding, the Western 220-gr. boattail with just a pinpoint of lead exposed at the tip, and the Remington 220-gr. delayed mushroom, which had a lead core with a hollow point but was covered with a full jacket. I don’t think a better all-around bullet for the .30/0.6 than the 180-gr. Western open point has ever been made.

Before World War I, anyone wanting a bolt-action big-game rifle either had to import a Mauser from Germany or a Mannlicher-Schoenauer from Austria or cook one up himself. Many Americans got 1903 Springfield military rifles and had them converted. Some of the first of these sporting Springfields were made by Louis Wundhammer, a German-born gunsmith practicing in Los Angeles, for the novelist and African hunter Stewart Edward White and Capt. E. C. (Ned) Crossman, who was my predecessor as an OUTDOOR LIFE gun columnist. The late Col. Townsend Whelen, who was also on the staff of this magazine at one time, had a Springfield sporter built by another transplanted German smith named Fred Adolph.

Back in the good old days, between 1914 and 1932, a member of the armed services or of the National Rifle Association could buy a 1903 service rifle for anywhere from $15 to $30 and then have a gunsmith restock it, fit sporting sights, and in general fancy it up. Among the famous remodelers of the Springfield were Wundhammer, August Pachmayr (father of Frank Pachmayr) of Los Angeles, Bob Owen who had a shop at Saquoit, New York, and later at Port Clinton, Ohio, and who was for a time head of the Winchester custom gun department, Adolph G. Minar of Fountain, Colorado, R. D. Tait of Dunsmuir, California, Alvin Linden of Bryant, Wisconsin, Griffin & Howe of New York, Niedner Arms Corp., of Niles, Michigan, and Hoffman Arms Co., of Cleveland, Ohio, and later Ardmore, Oklahoma.

This list of the great smiths of yesteryear will no doubt bring tears into the eyes of my older readers, and as I write this I am racked with sobs. All of these individuals and firms specialized in remodeling and restocking the 1903 Springfield, and some very wonderful work they did. Griffin & Howe, Owen, Hoffman, Linden, and Niedner Springfields were famous the world over among aficionados of fine firearms, and one in mint condition today is a collector’s item worth more than its original cost.

In addition, a big-hearted Uncle Sam sold to members of the N.R.A. a Springfield sporter with a star-gauged barrel, an oversize sporting stock, and a Lyman 48 receiver sight for as little as $40. This no doubt brought joy into the hearts of Savage, Winchester, and Remington, who had to make .30/06 rifles, cut the jobber and dealer in for a modest bit of gravy, advertise, pay taxes, and yet try to set aside a few dimes for the stockholders.

Right after World War I, Remington brought out the Model 30 Express for the .30/06 cartridge. To build it, they utilized the tools for the 1917 Enfield, which they had built in tens of thousands for the British in .303 and for the Americans in .30/06. However, the first factory-made American .30/06 bolt-action rifle was the ill-starred Newton which got into limited production about 1915 but which never really got off the ground. In 1925 Winchester brought out the famous Model 54 in .30/06 and .270. About 1937 it was revised as the Model 70, which is still manufactured. Savage’s first experiment in bolt-action rifle manufacture was the Model 1920 in .250/3000 and .300 Savage. The action was too short for the .30/06, and the firm later brought out a non-Mauser type bolt action called the Model 40 with no checkering and open sights and the Model 45 with checkering and a factory-installed receiver sight.

Remington continued to make the Model 30 (basically a 1917) until the outbreak of World War II. The final model was called the 720. The original .30/06 sporter, the Model 95 Winchester lever action, was discontinued after World War I because careless citizens blew some of them up by shooting 8mm Mauser military ammunition in them. After World War I, some very fine .30/06 rifles made by the great Mauser-Werke were imported into this country, largely by Stoeger Arms Corp. of New York, along with a few very fancy rifles on Mauser actions from Heinrich Krieghoff of Suhl. Some .30/06 rifles and carbines were also made on the Mannlicher-Schoenauer actions.

Since the last war, Remington has brought out the now-obsolete Model 721 and 725 on a greatly changed version of the Mauser action which, with further modifications, is called the Model 700. Savage makes the cleverly designed Model 110 modified Mauser in both right and left-handed actions. Weatherby has made rifles for the .30/06 as well as for the Weatherby calibers. Remington turned out the Model 740 semiautomatic in .30/06 and various other calibers and now calls a redesigned version the Model 742. The Model 760 Remington pump is also chambered for the .30/06.

Many .30/06 bolt-action rifles are also imported — the F.N. Mausers, the American-designed but Belgian-manufactured Brownings, the Swedish Husqvarnas, the Finnish Sakos, and the British B. S. A.’s. Marlin, Colt, and High Standard have made .30/06 rifles on Mauser actions, and British gunmakers put together flossy rifles in that caliber for the custom trade on Mauser and Model 1917 actions.

Along in the 1920’s, when there was much talk of long-range machine-gun barrages, the U.S. Army adopted the M-1 version of the .30/06 cartridge for the Springfield. It used a 172-gr. boattail bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2,660 fps. This was a fine cartridge, very accurate and flat shooting, particularly at the longer ranges. However, the recoil was a bit grim for many, and it didn’t work too well in the M-1 Garand. As a consequence, we fought World War II with the Garand and the M-2 cartridge, which for all practical purposes was the original .30/06 cartridge with a 152-gr., flatbase bullet at a slightly stepped-up velocity of 2,800 fps and a gilding metal or gilding-metal-on-steel jacket instead of the miserable old cupro-nickel jacket of the original bullet.

Along in the middle 1920’s, the use of progressive burning powders such as No. 15½ and No. 17½ made possible the stepping up of the velocities of all sporting cartridges, including the .30/06. The 220-gr. bullet was hopped up from 2,200 to about 2,400, the 180-gr. from 2,500 to 2,700, and the 150-gr. from 2,700 to about 2,950. Since then, factory ballistics have remained about the same, and it is not possible for the handloader to improve on them much with permissible pressures.

At various times a whole flock of different bullet types have been made for the .30/06-open points, bronze points, capped soft points, sharp noses, round noses, boattails, and flat bases and likewise different bullet weights, 110, 125, 130, 145, 150, 160, 165, 172, 180, 190, 200, 220, 225, and 250-gr. Those who like the various weights can put up pretty good arguments for them, but actually bullets of 150, 180, and 220 gr. pretty well take care of any situations the big-game hunter may run into. The 150-gr. is a fine weight for deer, antelope, sheep, gazelles, wild goats, and game of that weight. The 180 is fine for elk, moose, grizzlies, and almost all African antelope. The 220-gr. bullet will give deep penetration on moose, lions and tigers, the largest African antelope, Alaska brown bears, and so on.

I have shot some sheep, pronghorn antelope, and several dozen deer with the 150-gr. .30/06 bullets, and elk, moose, grizzlies, African antelope and zebras with the 180-gr. bullet. If there is any use in North America for the 220-gr. bullet, it is for moose and the big Alaska brown bears. Since the day up in the Yukon over 15 years ago when I put four 180-gr. Remington pointed soft-point .30/06 bullets right through a grizzly from port to starboard and kicked up sand and gravel on the far side, I have never been able to figure out why anyone needs the 220-gr. bullet for deeper penetration on grizzlies. Another time with the same bullet I broke both shoulders of a goodsize grizzly and found the bullet on the far side under the hide.

For frontal shots on charging lions, one may need a strong 220-gr. bullet, for all I know, as the lions I have shot have been with a .375. This was the medicine used by Stewart Edward White back in the 1920’s. He put his trust in strong Western and Remington bullets of that weight for such work. Syd Downey, the famous East African white hunter, swears by the .30/06 with the 180-gr. bullets for most antelope, but considers the .30/06 a bit light for the great cats. For lions, he says the .375 Magnum is the world’s best medicine under most circumstances, but if Downey has to stop a really indignant lion he likes a .470 double with a 500- gr. soft-point bullet. The .30/06 is probably the most useful light rifle possible to take to Africa. I used one in 1959 and shot, among other things, three big zebra stallions. Each was killed with one shot and none went more than 50 feet.

I have used the .30/06 since 1915 when I qualified as Sharpshooter at the age of 13. I have used the caliber on mule and whitetail deer, elk, moose, black bears, grizzlies, pronghorn antelope, sheep, coyotes, jackrabbits, caribou, greater kudus, zebras, and a whole flock of African antelope about the size of deer. If anyone says that the .30/06 isn’t a fine caliber for about 90 percent of all African and Asiatic game or isn’t a good caliber for grizzlies, elk, and moose, I gently but firmly tell him he is full of prunes. If the .30/06 was such a punk moose or grizzly cartridge or so poor on African game, one would not find so many .30/06 rifles in the hands of guides and white hunters.

I am not a guy who considers that all cartridge development stopped back in 1906 when the .30/06 came along. The .30/06 was widely used on woodchucks, jackrabbits, and coyotes by varmint hunters back before we had good varmint cartridges. I have never cared for it as a varmint cartridge. It makes too much noise and kicks too much for casual varmint shooting, and most 110-gr. and 125-gr. bullets lose their ambition pretty fast and generally do not give the fanciest accuracy. If I had to tackle an Alaska brown bear, a lion, or a tiger I’d a good deal rather have a .375 Magnum or a .338 in my hands.

How much game I have shot with a .30/06 I cannot say, but I have used the .30/06 and the .270 more than any other calibers. I have owned Springfield sporters by Owen, by Griffin & Howe, by Linden, and by Minar, a neglected genius who died before his fame was widespread. I have also owned one of the famous N.R.A. sporters which cost me $40 plus express. I have likewise owned a Model 30 Remington and Model 54 and 70 Winchesters.

At one time the .30/06 sporter on the Springfield action was considered the very top. Nowadays, the chap investing from $500 to $1,500 in a fine .30/06 would be more apt to get one built on a commercial Mauser or a Model 70 Winchester action. I now have three .30/06 rifles — one on an F.N. Mauser, one on a Springfield, and one on a Model 70. My pet of pets, not only because it shoots well but because it is a very lucky rifle, is one I had put together about 1946. It has a 22-in. Sukalle barrel with a 1-12 twist, a Lyman 48, and a ramp front sight. In addition, it is fitted with a Lyman 2½X Alaskan scope on a Griffin & Howe mount. Al Biesen stocked it for me with a fine piece of Wisconsin black walnut.

I have taken some very fine heads with this rifle — a 43 in. Dall ram and a 60-in. greater kudu, for example. This .30/06 will shoot into between 1½ and 2 in. with any good bullet, and has the pleasant habit of putting various bullet weights fairly close together.

Read Next: Jack O’Connor on the .270 Winchester vs .30-06 Springfield

Sighted to put the 180-gr. bullet 3 in. above the line of scope sight at 100 yd., it lays the 150-gr. bullet at about 250 fps higher velocity right to the same point of impact. The 180 is at point of aim at 225 yd. and the 150-gr. with 55 gr. of No. 4320 on at 250. For this musket I use 50.5 gr. of No. 4064 with the 180-gr. bullet. Velocity in my 22-in. barrel is 2,715. So sighted, the 220-gr. bullet in front of 56 gr. of No. 4831 for a velocity of 2,400 is exactly at point of aim at 100 yards. For whatever the reason, this little rifle never changes point of impact. I can leave it in the rack for months at a time, take it out, and it puts them right where it did last year or three years ago.

Great cartridge, the .30/06, the best seller in the bolt action. The only cartridge that has ever threatened its supremacy is the .270, but it has never caught up with the .30/06 in sales. The .308 may threaten it, but it is still behind the .30/06 in popularity as well as ballistics.

For sheep hunting I’d a bit rather have a .270 than a .30/06, and I also prefer a .270 for antelope hunting and open-country deer hunting. For big, soft-skinned stuff that shoots back, such as lions and Alaska brown bears, I’d rather have a .375. For varmints I’d take the Swift or the .243, and for deer in heavy brush I like a light, lever-action in .358. But for all kinds of jobs in the open and in timber, on big animals and small, at long range and short, there isn’t anything any more versatile than this perpetual best seller, the 56-year-old .30/06.

Read the full article here