I Spent Thanksgiving with Southern Hunters Who Ran Deer Hounds. Here’s What I Learned

This story, “Yalobusha Deer,” appeared in the Nov. 1962 issue of Outdoor Life.

For the big-game hunter who likes to fire at a fleet and agile target to the accompaniment of dog music, I recommend shooting whitetail bucks ahead of a mixed pack of Walker and black and tan deer hounds in the Mississippi Delta cotton country. The two-week, split season in Mississippi is opened in keeping with the tradition of hunting deer during the Thanksgiving and Christmas and New Year’s holidays. A hunter is allowed one buck during each half of the season.

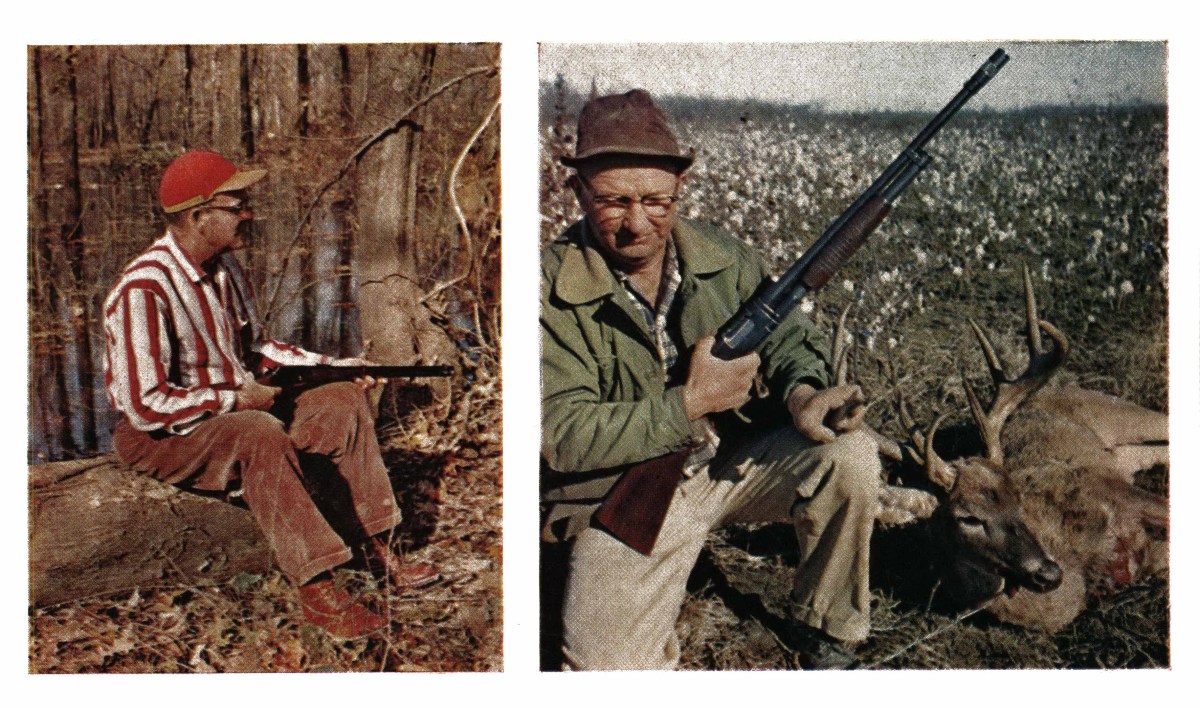

Last November, Franklin Smith, an old friend and bass-fishing companion, invited me to join his neighborhood deer camp deep in the fork where the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers converge to form the Yazoo at Greenwood. I accepted with alacrity, for I had been a frequent visitor in the camp and knew it had one of the best kill records of any camp its size in the Delta. Besides, the editor of OUTDOOR LIFE had asked me to keep my eyes open for a good whitetail story set in this northwestern part of Mississippi. I armed myself with only a camera and a bag of accessories, determined to devote my entire attention to photography rather than to take a chance on muffing both the pictures and a possible shot for a kill.

Early the first morning that I was in camp, I went with Franklin to start a drive. He parked the dog truck in the edge of the Pugh Field, site of an ancient ferry landing on the Yalobusha River, and we released the hounds 45 minutes after we left the camp.

The pack, with Franklin and me close behind, ran 50 yards across a cotton patch and scattered in a willow thicket that was shot through with sign. Buck struck hot scent immediately and gave out with a deep-throated squall. The old hound was unquestioned by his teammates. Long Shot wailed an acknowledgment, and the pack rushed to Buck to help unwind the trail. First one dog bawled, then another as they leapfrogged and accelerated their pace along the downwind trail. Then the deer jumped and the pack opened in full cry. Chills ran up and down my spine. I wondered if this were the beginning of the end of the jinx that Franklin told me had been riding the hunt.

I couldn’t get away from my home in Memphis, Tenn., until late the second day after the season opened November 20. I drove 100 miles to the little town of Money about 10 miles north of Greenwood, crossed the Tallahatchie, and arrived in camp at midnight. I found a vacant cot in the sleeping tent and sacked in unannounced.

The dogs had been chosen well to make one of the most melodious and formidable packs of deer hounds in the state of Mississippi.

The next morning, day broke mean and ugly with a strong, moisture-laden wind blo wing out of the southwest. I’d been up about 10 minutes and was brewing coffee when Franklin poked his head through the tent flaps. “Morning, Bob,” he said. “Glad you could come. Going to be a mean day for a drive. That wind must be blasting at least 20 miles an hour.”

“How about a cup of coffee?” I asked, adding that Willie Davis, the camp cook, had breakfast almost made in the cook shack. While we sipped our coffee, Franklin told me about the tough luck that had plagued the camp.

“We’ve been in the woods two whole days and still haven’t killed a young buck for Thanksgiving,” he complained. It was a custom of the camp to celebrate Thanksgiving Day with an elaborate dinner featuring tender venison steaks. Franklin said that Jean Everett, going to his stand on opening day, had jumped and killed a big, six-point buck, but the meat was tough as shoe leather and would require special treatment before being palatable.

“It’s been raining baby bluegills for weeks,” he exaggerated. “If it wasn’t for the flood-control reservoirs along the edge of the hills, this whole country would be under water.”

Generally, the Delta terrain is flat and always has been plagued with floods. During recent years, dams have been built across four turbulent rivers, just before they emerge from the hills, to trap excessive rainfall before it gushes down on the plain. Even so, Franklin explained, the regular range had been flooded, and the hunters had had to work the ridges in unfamiliar territory south of camp. Many of the hills were completely isolated by water, a situation much to the liking and advantage of the deer. At night the animals waded out to feed in the woods and fields and returned to the high ground to rest during the day. It was difficult for the dogs to get a buck straightened out in a race because of the myriad scents and trails on the ridges. “The deer kill nearly always is reduced during overflow conditions in the Delta,” Franklin said.

To make matters worse, he explained, the shortening daylight hours had triggered the rut and the bucks were reluctant to be chased away from the does.

“The water will be off our regular range north of camp by this morning,” Franklin said. “We scouted it for sign yesterday. We’ve just got to have a spike for Thanksgiving.”

The dogs, penned behind the cook shack, must have recognized the tall, slim cotton planter for they joined in a chorus of yelps and whines the moment he walked up to the fire. Four Walkers belonged to Franklin. Two Walkers and six black and tans were the proud possessions of Harold Terry and Henry Everett. It was a carefully chosen pack, weeded and blended from the day the dogs were born until the time they were ready to join the team. Franklin’s Buster, a Walker, had a fine, short bark that harmonized with the coarse, long voice of Everett’s Sally, another Walker. Long Shot, a misnomer for another big, rangy Walker had a deep bass and was noted for the speed with which he could straighten out a drive. Long Shot called the dogs the second a trail was scented and flanked them to foil any smart old buck that might try to jump out of the race. Buck, an ancient black and tan that would be retired after this season, was the best jump dog in the pack. Black Willie, another black and tan, barked with a medium chop and was Buck’s understudy.

The Walkers excelled as runners of great stamina, but they were hard to control. The black and tans had the best noses on a cold trail and they could be managed easily, pulled from the trail of a doe and cast after a buck jumped by hunters. The pack worked beautifully together. According to voice and talent, the dogs had been chosen well to make one of the most melodious and formidable packs of deer hounds in the state of Mississippi, where 80 percent of the whitetail deer killed are hunted with dogs.

Willie called us to breakfast, and the hunters began to file out of the tent. All lived in the vicinity of Money and all were in one phase or another of the cotton business. I shook hands with Franklin’s older brother and my good friend, Dee Smith. I was glad to see Harold Terry and Henry Everett and a flock of Henry’s nephews. Myles Flynn and J. K. Tate would come in the following morning. Kirk Hobson completed the roster of hunters already in the camp. These were veteran deer hunters wearing hip boots and drab, green-and-brown clothing rather than the popular red or yellow. They were seasoned woodsmen who had hunted together for many years, and they did not fear killing or maiming one another. A stranger or careless hunter was not admitted to the camp.

We put away Willie’s hearty breakfast while Franklin gave last-minute instructions to the standers. “Bob and I will start the drive on the Yalobusha River about two miles downwind from camp,” he said. “Keep your eyeballs peeled every second, unless you want boiled rump roast for Thanksgiving. In this high wind you might not hear the dogs and let a plump spike run right by you.”

He’d give the standers 45 minutes to take their positions and advised them to get their smoking and constitutionals over with before they left the camp. “Be careful,” he said, sternly. “The law says we can’t shoot anything without horns.”

We loaded the dogs in the truck and headed west toward Money for we’d have to drive 12 miles around the swamp.

In about 90 jumps out of 100, a buck will run into the wind, or at least quarter into it, so he can smell anything that stands in his path. He’ll veer off course if he senses danger but will swing back into line when he’s passed it. His ability to distinguish motionless objects is only fair, but any motion, however slight, shouts a warning to him. His sense of hearing is acute, and he can identify sounds. But above all else, he depends upon his superb nose for self-preservation. The practice of driving upwind puts the standers at a disadvantage because of the deer’s keen sense of smell, but it cannot be avoided. If you try to drive a buck with the wind, he can’t be counted on to follow his usual trails, and the standers’ best calculations are of no avail.

When Franklin remarked that the hunters had scouted the regular range the previous afternoon, he meant that they had gone over it carefully, searching for and analyzing deer sign. They’d spotted the favorite feeding grounds and bedding places and located the scrapes where bucks had honed their antlers against saplings and pawed the earth in their belligerence toward one another and in their mounting passion for the does. The hunters had paid particular attention to the narrow, hoof-cut trails and runways the deer used to move from one hangout to another, because it was at junctions and at other strategic points along these paths that they would station themselves during the drives. Deer are creatures of habit. According to Dee Smith, and verified by dates of hunts and hunters’ initials still in the bark of hackberry trees, some of the stands taken on this hunt were used by hunters 50 years ago.

The previous night after supper, cards had been cut for the choosing of stands. In a small camp like this one where fewer than a dozen standers cover an area some six miles deep and two miles wide, the success of the drive depends as much on the hunters’ skill in choosing stands as on their marksmanship.

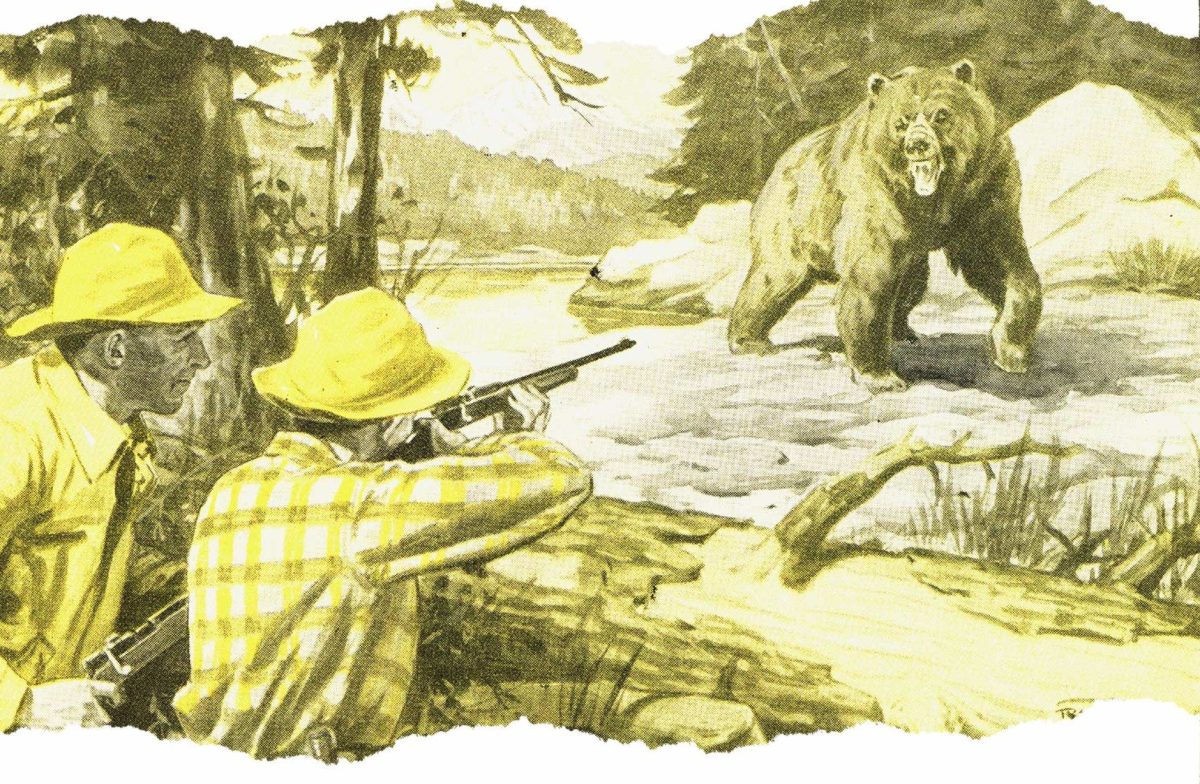

I went along with Franklin to start the drive because I wanted to get a picture of a buck and the dogs in a race. It would be a miracle if I got the chance, because a buck usually doesn’t want a pack of dogs close enough to pose in a picture with him; however, if the opportunity came it would be at the beginning of the drive. Any jumped deer would take off at breakneck speed, abandoning all precaution. Then he’d turn into the wind, and, after he’d run about a mile and put a wide distance between him and the dogs, he’d seek out one of his regular trails and slow down to a lope or a walk, stopping often to look, listen, and smell before carefully proceeding. If the buck circled back by us before the dogs straightened him out, I just might get my picture.

From Money, Franklin and I drove north two miles, then turned northeast across Six-Mile Lake and worked our way through fields and woodlands to the Yalobusha River about two miles east of the McIntyre Scatters, a huge, sprawling cypress brake at the head of McIntyre Lake (see “Miracle of the Scatters,” OUTDOOR LIFE, June, 1958). That was when we cast the dogs into Pugh Field, as I said at the outset.

When the pack lined out downwind after the jump, Franklin sprinted toward a strip of timber behind the truck and yelled for me to sit tight and have my camera ready. “If it’s a buck, he’ll circle and head into the wind,” he said. “One of us might get a shot.”

The wind had torn a rift in the clouds and sun was shinning brightly. I propped my back against a red oak and checked my camera, focused the distance on infinity, set the shutter speed at 1/100 second and aperture at f/11. Then I kept my eyes on the edge of a woods in the direction of the bedlam raised by the dogs.

As soon as I was out of the line of fire. Franklin let go with three shots at the buck, quartering away from him at 100 yards.

Suddenly, the pack turned and bore straight toward me. A doe broke out of the woods which bordered the cotton patch on the north. Moments later, a monstrous buck appeared, and the pair tore across the cotton patch straight toward me. The dogs exploded from the woods not over 100 yards behind the buck.

Without looking down, I rolled the focusing knob on my camera to 20 feet, because that was how close the deer would pass me. I changed the shutter speed to 1/200 seconds and the aperture to f/8. Then I couldn’t see anything but buck and horns. If I’d squeezed the shutter release at that in foreground in ground glass and the dogs would have been entering at the top. But I didn’t release the shutter. I didn’t even aim the camera. I couldn’t. The deer thudded away down a cotton row behind me. Then the dogs blasted by.

As soon as I was out of the line of fire. Franklin let go with three shots at the buck, quartering away from him at 100 yards. The distance was too great, for by that time the buck was jumping 20 feet to the stride and zigzagging. The shots were fired more as a signal to the standers that a buck was running than with intent to kill.

It wasn’t a fair shot, so Franklin’s shirttail was safe. I wondered about mine. Franklin ran over, smiling. “Boy, you must have got a honey of a picture,” he said.

“I didn’t shoot,” I replied, real low.

“You didn’t what?” he demanded in amazement. Then he sneered, “Buck fever! Well, let’s get going. We’ve got a well-racked buck making a beeline for the Scatters.”

A deer holds no aversion for water, and its use to wash away scent is the animal’s best stratagem for eluding hunters and dogs. The hounds will swim after him across a narrow slough or bayou and pick up the trail on the other side, but they’ll lose him if he sprints across a wide, shallow pan of overflow water, plunges into a big brake, or swims down a river.

Franklin Smith, in his early 40’s, is the best woodsman I know. Lean and wiry, be set a painful pace through two miles of swampland. It was all I could do to keep him in sight. The deer passed north of Flynn on the Yellow Elm Stand ( a landmark splashed on a tree with yellow paint), and the dogs lost them in the Scatters. Franklin gathered the hounds with his horn, and we set them to hunting back toward the truck for a new trail. In about an hour and a half, Black Willie jumped near the Duck Hole, a small, swampy lake south of the Pugh Field. The last we heard of it, the pack was running straight toward the standers. “If that deer keeps on course,” Franklin said, “it’s going to run right over Shorty on the Lost Lake Stand.”

We went back to the truck and set out for camp. Normally, we’d have stayed for a possible rerun of the course from the other end, but the sky had turned dark and it was beginning to rain. No deerhound on earth can hold a trail in a downpour.

On the long ride to camp, I admired the beautiful Delta landscape, now washed by a gentle rain. The late David Cohn, eminent Greenville author, said that the Delta starts in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row beneath the bluffs of Vicksburg. The giant, leaf-shaped plain, 50 miles wide between Greenville and Greenwood, is walled in on the west by the Mississippi River levee and on the east by the sheer cliffs at the foot of the Mississippi hills. In the winter, it’s a land of vast, snowy-white cotton fields hemmed in between bare, brown forests and swamps that mark the courses of swift, rain-swollen rivers and bayous. In the spring and summer, the Delta is an angler’s paradise, in fall and winter, a mecca for hunters.

“Franklin, what was the biggest buck you ever killed?” I asked above the whisper of rain on the truck’s roof.

“One morning I started a drive at the camp just as the sun peeped up,” he answered. “The dogs jumped quick and ran a doe and fawn into Sorghum Mill Lake. I blew them back and cast them again. They scattered. About 9 o’clock, Long Shot hit a hot track and lined out west, running plumb out of hearing. If it was a buck, I figured he’d swing north and come back down an old trail about a mile north of where I was, so I took off as fast as I could.

“I’d watched the trail for over an hour and had just about given up hope when I thought I heard old Long Shot. Then I could hear him plainly. He was really dogging that deer. I glanced to my left front and there was a monster buck coming at a fast, easy lope. At 15 yards I raised my 8 mm. Mauser and centered his neck with a 180-grain soft-nose bullet. He fell like a wet boot. The buck had 12 points and weighed 260 pounds, the largest ever killed from this camp.”

We got back to camp in time for me to get a picture of Sno and Fat Everett amputating Shorty’s shirttail. “Bob, did you get a picture on the jump?” Harold Terry asked.

“No, he didn’t,” Franklin answered for me. “But a king-size buck, a doe, and a whole flock of dogs almost ran over him.”

“Get his, boys,” Henry Everett ordered, and they bobtailed my new red shirt a good two inches above the belt line.

Henry filled us in on the stander’s end of the drive. The deer Black Willie jumped was a doe and she ran right by Shorty. The trouble started when Shorty stood up in the bed of his pick-up for a better view of the race. In the commotion, a spike buck got up from a weed field nearby and tried to slip away. Shorty opened up with three blasts of No. 1 buckshot from his full-choke, 12 gauge automatic and took off behind the spike, reloading as he went. He got in three more shots at the deer with slugs after it swam a bayou and before it disappeared in a canebrake, white flag still high in an impudent signal that it wasn’t even nicked.

Dee and Harold left in a truck to try to locate the dogs that might still be running the doe somewhere between the camp and Greenwood. Bad luck still rode the camp.

I went to bed early that night. A torrent of rain beat down on the tent until the wind switched to the north. Within two hours the temperature dropped from 60° to 28. I pushed down deeper in my blankets and slept like a baby until Willie routed us out for breakfast.

It was Thanksgiving Day, and the 20-mile wind had slackened to a five-mile breeze. The ground was white with frost. The sun rose big and red with promise. “Perfect day for a drive,” Franklin said, gleefully.

Because of the shift in wind direction, Franklin and I swapped sides with the standers and chatted over a second cup of coffee while they were going to their stations, principally the same ones as the day before. We talked about the terrific increase in Mississippi deer, estimated to be over 125,000 in 1961.

During the late 20’s, whitetails were almost extinct in most of Mississippi. In 1932, the newly organized Mississippi Game and Fish Commission closed the season and inaugurated a vigorous restocking and game-management program.

Four hundred deer were imported and released in rigidly protected refuges. As the deer multiplied, about 2,500 were trapped and stocked in every county in the state. The success of the program exceeded all expectations. The prolific rate of increase during recent years is indicated by the fact that only 3,700 deer were killed as late as the 1956 season compared with a total of 9,700 bagged in 1960.

Franklin, who is a deputy state game warden, told me about a recent conversation he’d had with W. H. (Bill) Turcotte, game and fisheries chief for the commission. “Bill says we’ve become dangerously overstocked with deer in some areas along the Mississippi River. The bucks run smaller and are not as well antlered as our deer here in LeFlore County,” he said.

Bill told Franklin that for this season (1961-62) the commission had issued 100 antlerless deer permits to just one club in Bolivar County. The permits, of course, were for kills over and above the some 200 bucks that members of the big club could be expected to kill during the season. Other clubs in Washington and Bolivar counties were granted permits in keeping with the need to thin their herds.

“In LeFlore County, we’ve had no trouble keeping our deer and range in balance,” Franklin said. “That’s why we kill such big, fine bucks. I expect the standers are getting chilly and would like to hear a dog bark. Let’s turn them aloose.”

The hounds scattered in a sparse woods like pool balls on the break. They were still in sight when Sally sounded off. Long Shot squalled for the other dogs. The hounds strung out along the trail, barking intermittently. The deer broke away and the pack opened in unison, filling the forest with a continuous roar. We sat on a log and were enjoying the symphony when we realized that the dogs were swinging away from the standers. In a few minutes they turned back into the wind, and we heaved sighs of relief. One hound, however, kept going away toward the east, bawling for all he was worth. “It’s Long Shot,” Franklin said. “We’ve got deer running in two different directions.”

He guessed that a buck had tried to make a long jump out of the race and let the dogs go by after his running mate. “Long Shot was flanking the race, luckily on the right side, and caught him in the act,” Franklin said. The acoustics of the swamp were perfect in the crisp, frosty atmosphere. We could hear every twist and turn of the chase and pick out each dog by the pitch of its voice.

Suddenly, they stopped barking — “Just like you’d caught them in a sack,” Franklin laughed.

The hounds had overrun the trail at a turn or lost it momentarily in a stretch of water. Buster struck it up again, and the music resumed. Shortly thereafter, we heard three rifle shots in quick succession, followed by a single blast from a shotgun. The frenzy of barking dwindled to one half-hearted yelp. “Buck number one, I hope,” Franklin said, raising a finger. “I don’t like the sound of a barrage. I’d rather hear just one, echoing shot.” We took a stand at the south end of Sorghum Mill Lake and waited, knowing the hunters would cast the dogs again whether a deer had been killed or its trail lost by the dogs.

In about 30 minutes the hounds jumped again and ran a big circle around Splice Brake, a watery cypress jungle to our left front. Then Franklin got his single, echoing explosion. “Business is picking up,” he said. “That sounded like Henry Everett’s old 12 gauge double. If it was, that’s buck number two.” He raised two fingers.

“Henry doesn’t miss. Let’s get in the truck and find out what’s going on.”

We drove across a huge triangle of cotton fields that pointed at the edge of a dense swamp surrounding Splice Brake. Franklin parked, and we set out through the woods on foot. We hadn’t gone 100 yards when we met Flynn and Tate dragging a 225-pound buck by its huge, 13-point rack. Flynn, back on the Yellow Elm Stand, had killed the buck going at a fast clip after Dee glimpsed the buck and a doe trotting by his stand out of range. The three successive shots we’d heard were a warning signal from Dee’s .30/30. Tate told us that Henry Everett had gone to borrow a tractor to haul out a 10-point buck he had killed.

We returned to camp and were dressing the big deer when Henry drove in with his 200-pounder thrown across the tractor behind him. It was the deer that had circled Splice Brake. With remarkable speed, Henry, anticipating the deer’s course, left his stand on the eastern end of the brake and intercepted the buck as it swung around an old trail that ran along the northern shore. He dropped it with a rifled slug not 100 yards from where Flynn had made his kill.

Also by this author — Gollywompers: A Secret Old Bait for Giant Bass

An hour later, face smeared with the blood of his first buck, Troy Everett came staggering across a cotton patch in front of the camp with our Thanksgiving dinner draped around his shoulders. We’d never known whether the spike jumped out of the race or whether, as Dee surmised, he was flushed by the first buck and doe. We do know that Long Shot kept doggedly after the buck until it finally took a trail that led by Troy, standing in the edge of a plowed field at the head of Horseshoe Lake. The young hunter killed the spike instantly with a close pattern of buckshot that went right into the rib cage.

It was a thankful group of hunters that sat down to a bountiful venison-steak dinner that night. The jinx was broken. Next year, however, I’d leave my camera at home; I’d rather have an attack of buck fever with a rifle in my hands.

Bullet Recovery

Many different methods of recovering fired bullets have been tried, but so far none have been entirely satisfactory. Bullets fired into water expand much as they would on watery tissue. Flight of fired bullets in fluffed cotton or wool is erratic. Cork dust stirs up a lot of debris. Gun nut I know fires bullets at long range into snowdrifts, then gathers them up when the snow melts in spring. He’s a patient hombre.

Winchester claims to have licked the problem by use of blocks of polyurethane foam, the same stuff that is sometimes used for cushioning bedding and furniture. In the lab, a series of blocks is lined up and the bullet fired from a distance of 4 ft. Bullets are recovered unmarked except for the rifling. — Jack O’Connor

Read the full article here