I Shot My First Buck on the Run, During a Low-Country Deer Drive

This story, “A Blooding in the Swamp,” first appeared in the January 1981 issue of Outdoor Life.

The November moon was in the half-cocked position, and the black sky was salted with stars. The Santee River was to my left, maybe 50 yards, and I could hear the water passing and the overhanging willow limbs that kept slapping it. There was no other noise in the Santee swamp in the South Carolina low country.

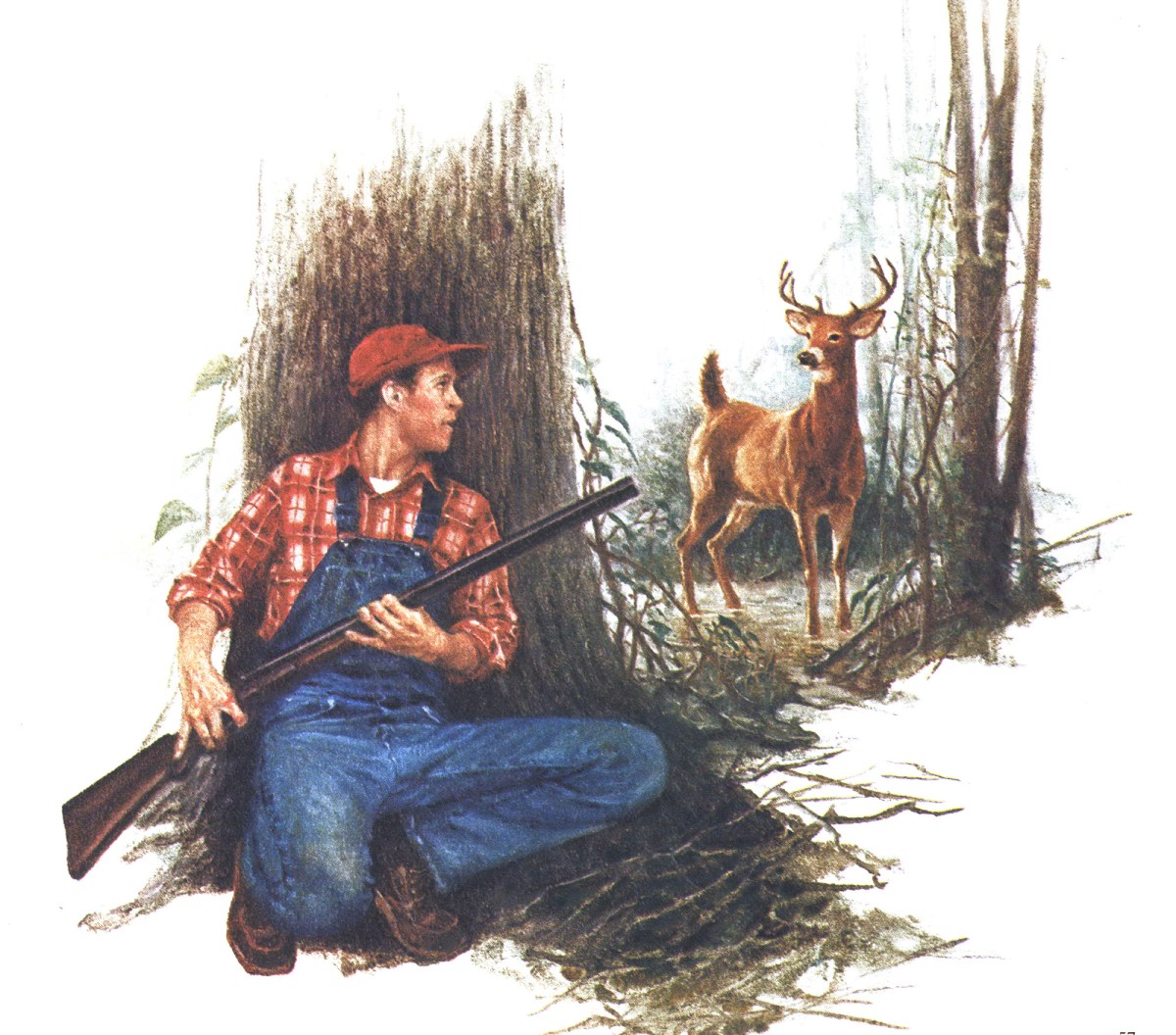

I scratched my back against the gum tree and pulled my knees in closer to my body to ward off the pre-dawn cold. In the gutter of my lap was a double-barreled 12-gauge L.C. Smith with 28-inch barrels. The right barrel was modified and left full choked. It was a plain gun with no engraving. It had been my uncle’s gun, and it had come to me in his will two years before. I was 14.

I tilted my head back and my eyes followed the black outline of the tree until it met darkness. Then I dropped my head between my knees. The heat from the long walk had worn off, and I was chilled from sweat and the moist riverbottom air.

It wouldn’t be long now before I would hear the bass voices of the hounds and the sharpness of Uncle Rich’s voice as he coaxed Rastas, Remus and Strawberry through the briers and cane thickets and hardwood flats as they routed a deer from its bed. Daylight would come, the air would warm, and Uncle Rich would show.

He was a cinnamon-colored man of maybe 5 feet 7 inches when he stood on his toes while picking wild grapes. Short and thin, his head rimmed with stubby, curly white hair and the center of it shiny and slick, Uncle Rich was ancient. Some said he was maybe 80 or 85. He didn’t know, but he was lately saying that some mornings it took his feet maybe an hour to catch up with his mind. He had but one tooth left and it was gold-capped. It was grandly displayed when he opened his mouth to talk.

Where did Uncle Rich come from? No one knew for sure. Some say he came up from the coast near the village of McCellanville where he had worked on shrimp boats and picked oysters during his youth. No one knew, and Uncle Rich never talked about where he came from. He just showed up one day in the Santee swamp and blended into the landscape.

There was an old logger’s cabin on the fringe of the swamp near Riser’s Old Creek and he took up residence there. He kept a garden and half a dozen laying chickens that pecked about the yard. His home was a sleepy sort of a place, especially in the spring when the wildwood went to budding and the birds began chirping in the flowering trees.

There were a lot of things Uncle Rich didn’t know or hadn’t seen. But he knew the Santee swamp and its moods. He also knew which way the deer ran when they jumped from their beds, where the mallards fed in the rain-flooded acorn flats in winter, and where bream bedded in the spring.

I had known Uncle Rich since I was 7 when my uncle toted me across streams in the swamp on days he went squirrel hunting with him. After my uncle died, Uncle Rich sort of gathered me in close, and we hunted and fished most every Saturday.

Daylight was coming now. The sun would be welcomed when it came. Then it would turn colder than it was now. It always turned colder after the sun showed its fresh red face, maybe because the wind blew for a while, but the cold wouldn’t last long. Overhead the rush of wings brought another sound to the swamp. The wing beats were fast; they belonged to wood ducks. The early starters were in singles and pairs, but soon flocks would arrive to feed in the shallow flooded flats thick with floating acorns.

I watched them as they came through the trees and plopped into a small creek where it opened into a flat. They would spend the morning there swallowing acorns before leaving for the river to preen in quiet eddies.

Day was born. Heavy frost in the swamp looked like white icing on a cake. The sky was deep blue spotted with puffs of white clouds. Squirrels started to bark, and crows were calling as they assembled a congress in a field on high ground. The wood ducks had ceased their morning flights.

I rubbed my hands along the slick gun barrels. They needed bluing, and the stock and fore-arm needed refinishing. Maybe I’d take the gun to a gunsmith after the hunting season.

It was time to hear the dogs and Uncle Rich as he came down from the high ground with Rastas, Remus and Strawberry. It was Rastas — the one with the broken tail — that usually jumped deer. Remus was a short-legged dog with a large white spot centered on his back. He was mostly beagle, but there was some other blood in him. Strawberry was a red-bone-bluetick cross with a long, lean body and an elongated face like a collie’s. Uncle Rich stood fast to his claim that there was no blood in Strawberry other than redbone and bluetick.

My stand was a good one. It was in a place where the land narrowed into a neck that extended until it joined a sandbar at the river’s edge. The ground was scarred with deer hooves since it was often used by deer coming back and forth across the river.

The sounds were familiar and comforting as they came through the swamp — the bass notes of the hounds and Uncle Rich’s accompaniment. The noise had broken up the crow congress, and its representatives now spotted the skies. The dabbling wood ducks left the water frantically, flew up through the trees, turned, and went downriver.

There was another noise, a noise kin to a man stumbling in shallow water. But no man was making it. This was a deer emerging wet from the creek. I counted six points on his antlers. They were pointed inward, as were his forward-cocked ears. The air was acrid with the pungency of freshly spent gunpowder.

Then the swamp was quiet again. A breeze came and blew away the smell of the shot. The deer was gone. Rastas nosed his way down the deer path to where the land narrowed and met with the sandbar and the river. He returned wet and came to where I stood. He lay down. Remus and Strawberry came and took their places beside him. Strawberry’s tail thumped the ground lightly.

“It’s a pityful ting,” Uncle Rich said as we walked a log across the creek to where the deer had appeared. “Ain’t so much as put a mark on him. Almost like he was a ghoast.” He stooped down and spread fingers into the deer’s hoof prints.

“I don’t … ” I started to say. “Ain’t no need to explain,” said Uncle Rich. “This is the third time he done it to me. I’m glad he’s cross the river. Maybe he’ll stay yonder for good. Let’s go to the house for dinner. I got some collards cookin’ slow, and maybe I got some cold sweet potatoes to go with ’em.”

The afternoon had no kinship to the morning. It was warm, windy and sociable. The morning’s clouds had all but passed unnoticed. The afternoon clouds bumped and socked one another. I felt the warmth of the wind against my face and listened to it pass through the broomstraw.

I could still see the deer as he came from the creek. I remembered getting up from the ground, fitting the gun-stock into the depression of my right shoulder, squeezing the forward trigger, then the rear trigger. I’d watched him as he passed by almost within arm’s distance, his head back and rocking gently as he sprinted to the sandbar and into the river. I could still hear buckshot rattling in the trees across the creek.

Maybe I should have shot from sitting. It would have been steadier. That was this morning. But it was no longer morning. I had eaten and had slept since then. It was afternoon now. I scanned the strawfield to the place where it connected with a branch thick with scrub oaks and loblolly pines. To the left of the strawfield lay a cutover cornfield. A flock of doves came into the cornfield and pecked the earth for spent kernels.

The long branch began at Uncle Rich’s house and slowly curved into a half horseshoe were it connected with the strawfield. Uncle Rich said it was possible that a deer would come from the branch, go into the field, and head for the river.

I squatted in the field and watched the branch for a deer. I wanted a drink of water. Uncle Rich had cooked his greens with too much salt pork, and the roof of my mouth was slick from the grease. The first waves of redwing blackbirds were en route to their roost, their craws filled with corn.

I saw one of the hounds break from the woods. It was Rastas, always first. Then I saw Remus and Strawberry drop in behind Rastas. Uncle Rich was waving his arms as he came out of the woods. Ahead of them raced a deer. I went prone in the grass and watched the hounds.

They were in full stride behind the deer. The buck was parallel to my left and maybe 30 yards out when I stood, turned, and fired once, then again. The deer went crooked-kneed, skidded through the strawfield, and died.

He was not a big deer. No, not at all. His antlers were not massive. No. He only wore a crown of four points, and one of them had been splintered by buckshot.

“You did Uncle Rich proud,” he said when he came along. “I just believe Uncle Rich gonna hug your neck.” And he did.

“You knocked him down,” he went on, removing his pocket knife and kneeling beside the deer. He slit the belly skin and white showed.

“Help me lift him to his side so’s I can get his insides out,” Uncle Rich told me. The knife made paper-ripping sounds as he worked. I saw the intestines spill onto the ground.

“That’s about all I can do in the woods. I’ll go back to the house for the truck. You stay with the dogs and keep ’em off the meat. But first I’ll make your first deer legal. Kneel down, so I can do it right.”

I did. The sun was gone; only traces of light remained.

It wasn’t sticky and it wasn’t salty like I had been told it was. Uncle Rich scooped blood with his cupped hands from the deer’s open cavity and annointed my head twice.

Read Next: ‘I Laughed, I Cried.’ After 36 Years, North Woods Hunter Finally Tags His First Deer

He wiped his hands dry with tuffs of broomstraw.

I looked up at him and he looked down and said, “You been blooded properly. You are a deer hunter.”

Read the full article here