Giant Florida Python Found Decapitated by a Bobcat

A team of python trackers and removal experts in South Florida have found evidence of a bobcat decapitating and feeding on one of the giant, invasive snakes in a python-infested area near Naples. Judging from the other clues they found, they say it’s likely that the bobcat also killed the python, a 13-footer that weighed more than 50 pounds.

This would be a promising development — proof that Florida’s native critters are, in some cases, adapting to the presence of Burmese pythons, which have no natural predators in the state and are wreaking havoc on wildlife populations in the Everglades.

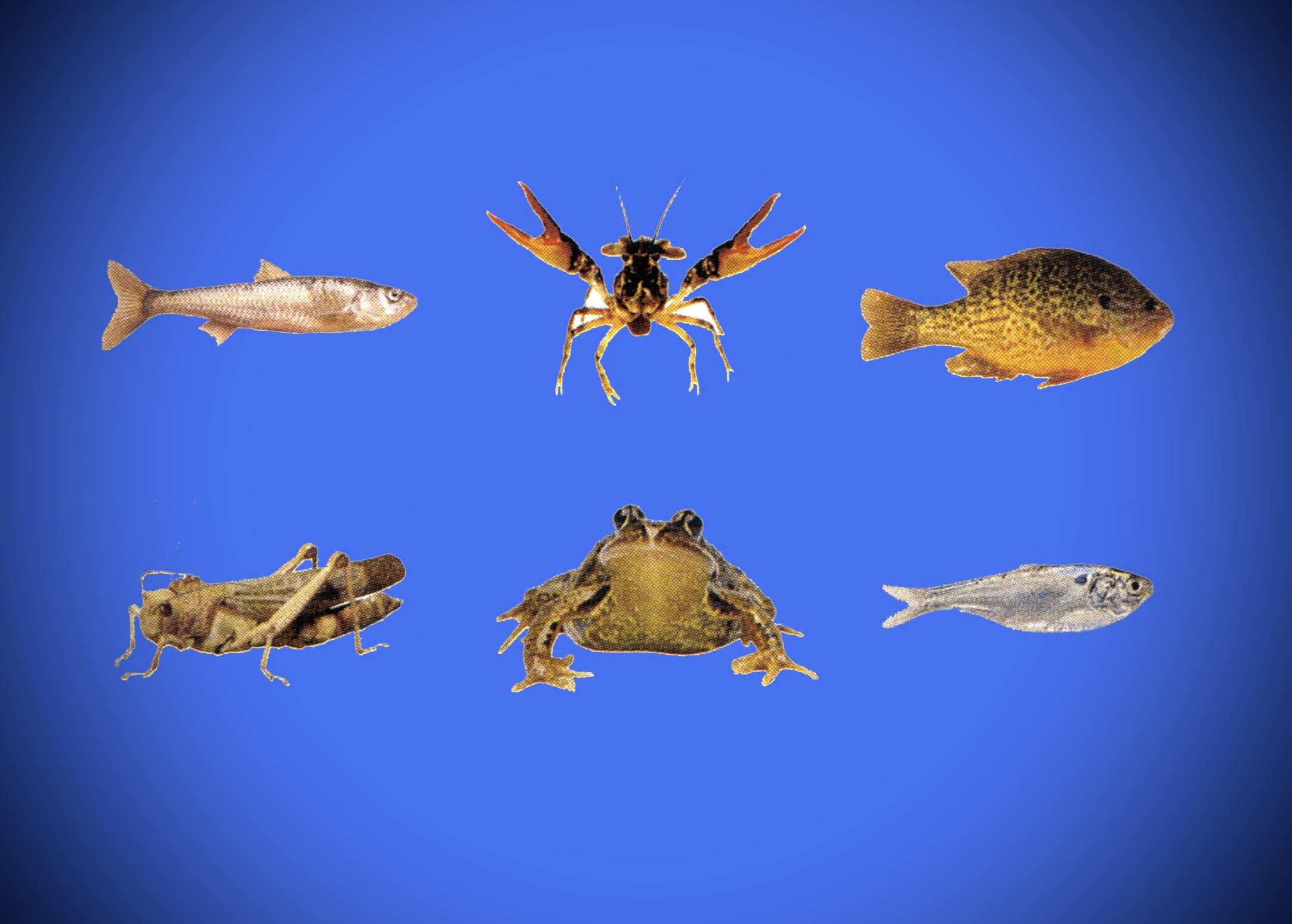

“The list of species [being impacted by these snakes] is up to around 85,” says Ian Bartoszek, the lead researcher who along with his team found the python that was fed on (and possibly killed) by a bobcat in December 2022. “It’s easier to make a list of what pythons are not eating, than it is to list all the animals that have been found inside pythons to date.”

A wildlife biologist and the science coordinator for the Conservancy of Southwest Florida, Bartoszek has spent more than 12 years tracking and hunting Burmese pythons in the area, so he knows what the predators are capable of. In October his team published the first-ever photographs of a python swallowing a full-sized whitetail deer in Florida. The photos proved his long-held suspicions that the snakes are literally “eating their way through the food web” of the Everglades. (That long list of species includes alligators, too, as other researchers have found.)

This is why, Bartoszek says, the discovery of a giant python being fed on and potentially killed by a native predator was so encouraging.

“It’s a score for the home team. The Everglades are fighting back.”

Catching the Cat on Camera

The discovery itself took place in December 2022 on some conservation land near Naples, in a region that Bartoszek identifies as the Western Everglades. This is where he and his team at the Conservancy focus their efforts, which entail tracking, killing, and removing as many pythons (especially large females) as possible. They do this primarily during the winter breeding season, and they use telemetry equipment and male pythons fitted with tracking devices — also known as “scout snakes” — to locate the big females.

Bartoszek explains that he, fellow researcher Ian Easterling, and some interns were tracking a large male scout snake they named “Loki” that afternoon in December. They’d seen Loki just days before and he was in prime condition, Bartoszek says. But as they approached Loki’s signal to get a closer look, they realized the 52-pound, 13-foot-long snake was not only dead. It was missing its head.

“We started seeing the clues around us. And it was like, wait a second, that animal is buried under the pine needles,” Bartoszek tells Outdoor Life. “This is a kill site.”

He says this realization quickly outweighed the initial disappointment he felt when they found the dead male snake, which had been part of the tracking program for over six years and was one of their best scouts.

“We started to pull away some of the pine needles, and we realized that the head and neck area had been chewed off and cached — which, to my knowledge, caching is typically a feline behavior in our area,” Bartoszek says. “So we were pretty sure it was a cat.”

Bartoszek’s money was on a Florida panther, or at least that’s what he wanted to believe. He contacted David Shindle, the Florida panther coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a former colleague of his at the Conservancy. Shindle went out to the site and set up a cellular trail camera, and the next morning, he emailed Bartoszek a short video clip that the trail cam had captured. It showed an adult bobcat returning to the cache to feed on the giant snake.

“So, I lost the bet,” Bartoszek says. “But it was probably even more interesting that it was a bobcat, because they’re more common.”

As a researcher, Bartoszek is not one to jump to conclusions. He says they’re “fairly certain” that the bobcat killed the big python, but it’s also possible that the snake died of other causes and the cat happened to find it soon afterward. Bobcats are primarily hunters, although studies have shown they will occasionally scavenge dead animals.

Read Next: Florida Python Trackers Remove Two Giant Mating Balls in Record Day of Snake Hunting

Bartoszek says there had been a cold snap in the area between the time they saw Loki “in prime condition” and when they found the snake decapitated. Because they are cold-blooded, freezing weather can and does kill pythons and other reptiles.

Bartoszek, however, doesn’t think it got cold enough to actually kill the python. What’s more likely, he says, is that the snake was cold-stunned and unable to defend itself from the bobcat, even though the cat was only half its size. (The average weight for a bobcat in South Florida is around 25 pounds, according to Shindle.)

“I would have loved to have seen that encounter,” Bartoszek says. “The possibility of a 25-pound bobcat taking down and killing a 52-pound, 13-foot Burmese python is impressive. And I like animals that punch above their weight class.”

Read the full article here