A Sneeze Turned into the Best Pronghorn Tactic I Ever Tried

This story, “Fishhooks on the Plains,” appeared in the August 1954 issue of Outdoor Life.

A sneeze was that buck antelope’s undoing. When Lee Hayne led me to the top of a ridge, where we hoped to glass a solitary old pronghorn, the sharp and tangy smell of sage finally got me. It tickled my nose unbearably. Though I buried my face in the rimrock, that sneeze exploded like a Comanche war whoop.

Lee lay taut beside me. “All you needed to match that one was a siren, or maybe a calliope,” he reproved me. Nevertheless he continued glassing the rolling slopes below us. Minutes later, while I was throttling another sneeze, he said, “Put your glasses just to the right of that biggest sage brush clump.”

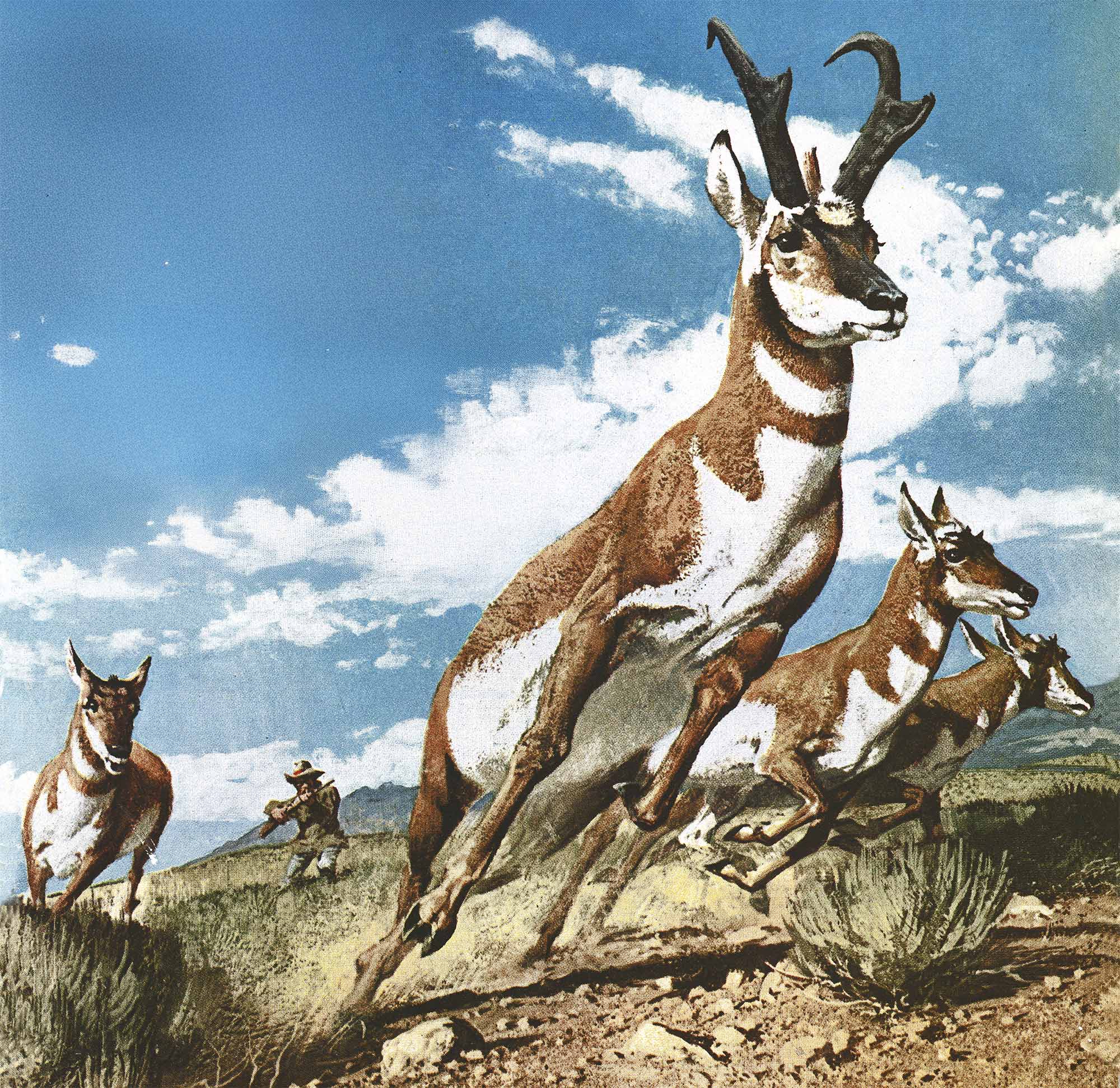

What I saw justified all our hours of walking and climbing and glassing. Projecting over the slope was a pair of “fishhooks” — the incurving hooks at the top of a buck antelope’s horns. They were pointed straight at us, as if the buck awaited an encore of that mighty sneeze in order to place and identify it more exactly.

For 15 minutes or more those horns held that rigid pose. For a solitary buck antelope has untold patience, far more than the average hunter, who’s usually the one to give himself away. The hunter moves, trying to get a better look, or a better shot, and the antelope is gone.

But Lee Hayne of Newcastle, Wyo., is no average guide. He makes a specialty of going after such wary loners, those bucks that hang out in little pockets, or in the middle of a vast sweep of valley, where a hunter can’t help skylining himself while making a stalk.

We had already glassed three such bucks, and rejected two as having inferior horns. The third buck rejected us. While glassing his horns, looking into the sun, I incautiously let my hands come back too far on my binoculars. The reflection of the sun on those glasses caught his eye. He gave us one long hard look, then took off in that effortless gliding run that makes antelope appear such easy moving targets.

“That was a dandy,” sighed Lee. “His horns would go 17 inches, maybe more.”

“He didn’t seem especially spooked,” I said. “Couldn’t we take after him?”

“Not from this direction,” denied Lee; “he’ll be on the lookout for us. Of course if we circled around and found him again we might pull a stalk from some other direction. But he may go one mile, or four or five. Finding him’s a chancy proposition.”

hat buck had been a good 600 yards away, in a wide valley having a minimum of cover, He had chosen his feeding station well, letting his marvelous eyes and fleet heels protect him from any interested hunters. I didn’t see how we could have gotten 10 yards closer to him, and I said so, I’ll paraphrase Lee’s reply:

When hunters spot a buck that’s moving, and undisturbed, they can always pull back over the ridge and circle ahead to intercept his course. If they’re careful not to show them selves, that buck is likely to approach close enough, some where along the line, to offer one good shot.

“One good shot,” Lee repeated, “that’s what a trophy hunter has to be ready for.”

As he went on to explain, when you come unexpected ly upon a buck, and take a few seconds to glass him and make sure he’s the one you want, you have only a few more seconds to kill him before he’s out of sight, or out of rifle range. Usually there’s time for only one good shot.

Now, we’d had perhaps a dozen bucks within 200 yards of my rifle that September morning, but they’d been with does and fawns. They had neither the experience to make them wary, nor the age to grow trophy-size horns. All together, I’d say we’d probably seen upwards of 350 antelope.

When we got back to Lee’s station wagon he climbed in and kicked the engine into life.

“Are you game to go into some really rugged country?” he asked. “Hunters can’t get around there on wheels, and they’re mostly too lazy to go it afoot, but that’s where the top trophies grow.”

“How about the buck that just took off?” I demanded. For any pronghorn that would make that last one look puny would be worth walking my legs off to get.

Lee grinned. “He really belongs in the back country. And I think that’s where he’s heading.”

“Let’s go,” I said. For Lee knew the country, and maybe this would be his chance to show me how he occasionally tolled buck antelope within rifle range by merely placing himself on some prominence within sight of them, then sit ting it out, hour after endless hour.

Such loners know their range down to the last clump of sagebrush. If anything new is added to the scenery, they can’t rest until they definitely identify it. So they’ll circle, blowing an occasional invitation to that unknown object to give itself away, and draw ever nearer. Eventually they get within rifle range, and if the hunter scores with his first shot he gets himself an outsize trophy.

“The trick is to place yourself so that a buck can’t identify you from any spot as a hunter,” Lee elaborated. “You can often break the human outline with a fence post or maybe a hilltop rock. Some bucks may spend two or three hours trying to identify you; I’ve seen others charge straight across a mile of sagebrush, like a moth to a flame.”

Lee drove miles before his next stop. En route he ignored 10 or 12 herds of antelope. I kept track and counted exactly 68 animals, none of which got more than a casual glance from him. There were perhaps 10 bucks in the lot, identifiable as much by their larger size as by their black headgear.

Finally Lee hit the rimrock trail he was seeking. From that vantage point we could see miles on both sides, down into ruggedly beautiful country. When the trail got so narrow that it looked as if it were used only by jackrabbits, and infrequently by them, Lee drove to the highest rise on that ridge and stopped. “We’ll leave the car here,” he said. “No matter how far we hunt, we ought to be able to see it from most any high spot in these parts. Wait,” he advised as I started to climb out. “Use your glasses. We might spot just the buck you want from here. If he’s watching us we can climb out on the off side, leave him watching the car as a decoy, and circle him to get a shot.”

We saw bucks, seven in all, but none of them looked like top-drawer trophies. Even so, Lee was cautious. We got out of the car on the side where only one of them could see us. “Never spook a buck if you can help it,” Lee observed. “For in making his get-away the one you don’t want may warn a trophy you’d give your eyeteeth for.”

Before we left, Lee made a final check of equipment. “One knife, one rifle, two sandwiches apiece, two bin oculars, and plenty of shells,” he ticked them off. “The binoculars and shells are most important. Without glasses, you can spend hours stalking a worth less trophy. And I’ve seen some crack shots use up a box of ammunition on running antelope before bagging their buck.” I already had six loads in my rifle, and a dozen in a belt, but I dropped another six loads of 130-grain Bronze Point .270 ammunition into a pocket.

Then Lee fooled me. Instead of staying high where we could see, he plunged down that slope on a long incline. Unless we were concealed in a draw, we seldom traveled 50 yards without using our glasses. That suited me, for it gave my lungs and heart a chance to keep pace with the country.

“Those bucks know the car trails better than we do,” Lee explained, “so they watch them and often neglect to keep an eye on the draws and cuts be low them. Besides, there’s less risk of skylining. yourself down in these cuts, and they’re good cover.”

We spent over two hours ranging that wildly broken country. In that time we saw only one small herd; all the rest of the antelope were lone bucks, some bedded, some standing, some grazing. With Lee’s stalking skill, we spooked only one of them.

Finally, on a flattened, sage-dotted ridge end, Lee called a halt. We sat down there and dug out our sandwiches, using our binoculars between bites. We wadded up the paper wrap pers and put a rock over them so there’d be no obvious evidence of our stop.

“There’s an unusually green bottom down there,” Lee pointed out when we were ready to go again. “Antelope like that greenery. In fact, if you sit over such a spot all day, you’ll see dozens of them come in for a few minutes, eat hurriedly, then move to a lookout spot. Let’s go down that way.”

But the only buck we saw there was bedded halfway up the slope, out of rifle range from both the bottom and the ridge above him. He felt so safe that he let us go by within 600 yards without leaving his bed.

Once out of his sight, Lee glassed ahead a minute and then suggested, “Why don’t you take another look at that lazy critter?” I tried to, but he was gone. Lee chuckled. “You see how careful they are,” he said. “As soon as we disappeared — where we might have stalked him — he moved out. And I’ll bet he keeps us in sight until we’ve quit these parts.”

Lee kept down in the main draw, where he showed just head and binoculars in glassing over the top of each gently rolling swell. Above us was the flat top of the plateau, with here and there a mass of jumbled limestone blocks that had weathered away from the rimrock edge. We angled up the plateau and stopped amid those rocks to scan ahead. That’s where we saw the fishhook prongs of a buck’s horns poking over a ridge across from us. And it was there that I cut loose with that re sounding sneeze.

Lee took one more look at those prongs and urged me behind a lime stone slab. “Get on the shady side,” he said. “Light won’t reflect off your bin oculars or your rifle there.”

The spot was ideal. A massive crack split the chunk of limestone in front of me, leaving an eight-inch corridor pointing straight toward the buck’s horns. I pushed my rifle into the slot and settled down behind my binoculars. Lee was right behind me, even deeper in the shadow.

“We can crawl around this slab and over the ridge without letting him see us,” I murmured. “Then we can get to the top of the ridge he’s behind and shoot from there.”

“How do you know he isn’t bedded down?” demanded Lee. “If he is, and gets curious, he’ll probably stand up just as we’re in plain sight. One quick look at us and he’ll be gone.”

I studied those motionless horns, now frozen head-on at us, for at least 15 minutes. Yes, he could be bedded down in low brush. “What’ll we do?” I asked. “Lay absolutely still,” advised Lee. “Be sure your safety is off, ready for a shot. By this time he must be busting with curiosity. When he can’t stand it any longer he’ll come take a look. Just don’t sneeze again.”

“How big is he?”

“Can’t tell for sure until he shows more of his horns. I think he’s as good

as that best one we lost this morning Watch it. He’s moving!”

The buck took a quick look up the slope, giving us just a glimpse of symmetrical, sharp-tipped prongs. Then the spread was pointed squarely at us again.

“How far away is he?”

“Over 200 yards. Maybe 300. It depends on how long those horns are. Having fun?”

“Sure. But I hope he isn’t rooted there,” I answered feelingly.

“Take your time,” counseled Lee. “Patience wins this game. Want me to wave at him?”

“Wave at him?”

“I can push my cap on top of this limestone. That ought to be high enough to catch his eyes. Then we’ll know if he’s bedded or standing.”

I considered the matter for some time. “Maybe that’ll spook him,” I said. “Maybe we’d better wait him out.”

“That’s what I’d do, if I had the gun,” Lee approved. “He knows there’s some thing here or he wouldn’t keep his fishhooks beamed on us. Give him time, and he’ll investigate.”

The horns made another brief flash, snapped back at us, took a quick swing toward the slope below, and aimed at us again.

“He’s breaking,” murmured Lee.

Suddenly the horns started to grow shorter. Then I realized they were also bobbing slightly.

“He’s walking — coming right at us,” said Lee. The fishhooks disappeared. “He may come out either above or below where we last saw him. Better swap your binoculars for your rifle.”

Lee had said the buck was coming; but when? Would he appear at such an angle that I couldn’t get a shot at him through that crack in the limestone? I wailed in suspense while the minutes plodded by.

Then Lee ended it. “Just a few feet higher up the slope,” he said. “About two feet to the left of that pointed clump of sagebrush. Take your time; he’ll keep coming until he’s in plain sight.”

But when I saw those horns show over the short grass of the slope my heart sank. For at first the step-down from 7×35 Bausch & Lomb binoculars to a 2 1/2 X rifle scope was shockingly great and those horns seemed all but invisible in my Lyman Alaskan. Then I realized that I was trying to hold my breath and that my heartbeat was bouncing the scope and blurring my vision. I took half a dozen deep breaths and looked again. That was better; lots better.

“Lee, I’m going to put this rifle down and take a good look at his horns with binoculars. Will he keep coming?”

“Sure, take your time,” he advised. “He has to come another 30 or 40 yards to be in plain sight. And I don’t think he can make us out in the shadow of this limestone.”

The buck came on until his head was skylined, then stopped and began an other round of patience. Never had I realized how little regard for time these prairie phantoms have. He was looking right at us, and I was afraid to take a deep breath for fear he’d make us out.

“Is he going to come any closer?” “Can’t tell. I never saw a buck this careful. And the way he’s standing he could be gone in two jumps.”

“Take it easy,” I said. “We have him over a barrel.”

“Over a barrel, hell,” Lee countered. “I feel as if he’s reading my mind. Maybe you’ll have to shoot him just as he stands.”

“Are his horns good enough?”

“If they aren’t 17 inches I’ll eat ’em. But, with a set of hooks like that, you’ll probably find his steaks as tough as his horns.”

I switched back to the rifle and again put the crosshairs on that skylined head. Then I squirmed over a bit and pressed my left hand hard against supporting limestone.

With such a solid hold I felt I could hit that head.

It should be a simple job to hit his body, if he exposed it.

“Lee, I think I can hit his head. Shall I take him?”

“You’re nuts! He must be nearly 300 yards away. Besides, hitting that skull would blow it to pieces, and you’d ruin the cape for mounting. You’d be better off to shoot for his body, just clearing the grass with your bullet and depending on its fall to get him. Only—”

“—We don’t know which way he’s standing,” I finished the thought in Lee’s mind.

“That’s right. Would it help if I waved at him? Or poked my cap over that limestone slab?”

“Anything to make him move a little bit. If it doesn’t work, I’m going to take him as he stands.”

I breathed deeply while Lee was sneaking the cap off his head. I put the crosshairs dead-center between his horns, just so I could see daylight all around to help with the hold. My finger snugged the trigger and began to ease it back.

Lee’s cap must have showed at the very instant I was applying the last half ounce of squeeze. For I distinctly saw that buck’s head lift alertly, inches higher. Then the bullet was gone, recoil jumped the scope off the target, and I listened.

The whock that drifted back to us was sweet to my ears.

“You hit him!” said Lee. “He reared high enough so I could see his shoulders. Get on top of that — he may need another shot.”

I tried to hurry, but it seemed I moved in slow motion. Worse, when I reached a good observation post and looked hurriedly to right and left, there was no buck in sight.•

“He’s gone, Lee. I must have missed him.” Then I raised the glasses. “Wait — I think I see something.” I hung the rifle on my shoulder and steadied the glasses with both hands. “Yep, I can just barely see what might be his ribs.”

Lee and I went down that slope, up the next rise, and topped out on the concealing ridge. Not until then could we see the buck, one hind leg drawn back. When we got there we found the buck’s face unblemished, though there was a pool of blood behind his head.

“Look!” Lee said, pointing to an inch-deep crease at the base of the left horn. He took the two horns and pushed them together. The right one was firm on the skull, but the left moved loosely an inch or two. “That is the damndest antelope kill I’ve ever seen,” he insisted. “And I’ve seen hundreds. Just how far was that shot, anyway?”

“I don’t know.” I brushed off the question, my eyes full of the clean-lined sweep of those majestic horns. Then I inspected the head. “A taxidermist can patch that bullet crease so it’ll never show. The head isn’t damaged a particle for mounting.”

Lee paced off that shot, back to the limestone shooting port and then back to the buck.

“It’s 373 paces,” he said. “A man can’t hit an antelope head at that distance.”

“I didn’t kill him, Lee; curiosity did.” And then I explained. If the buck hadn’t hoisted his head just as Lee’s cap showed over the limestone that bullet would have passed clean between the horns.

Read the full article here