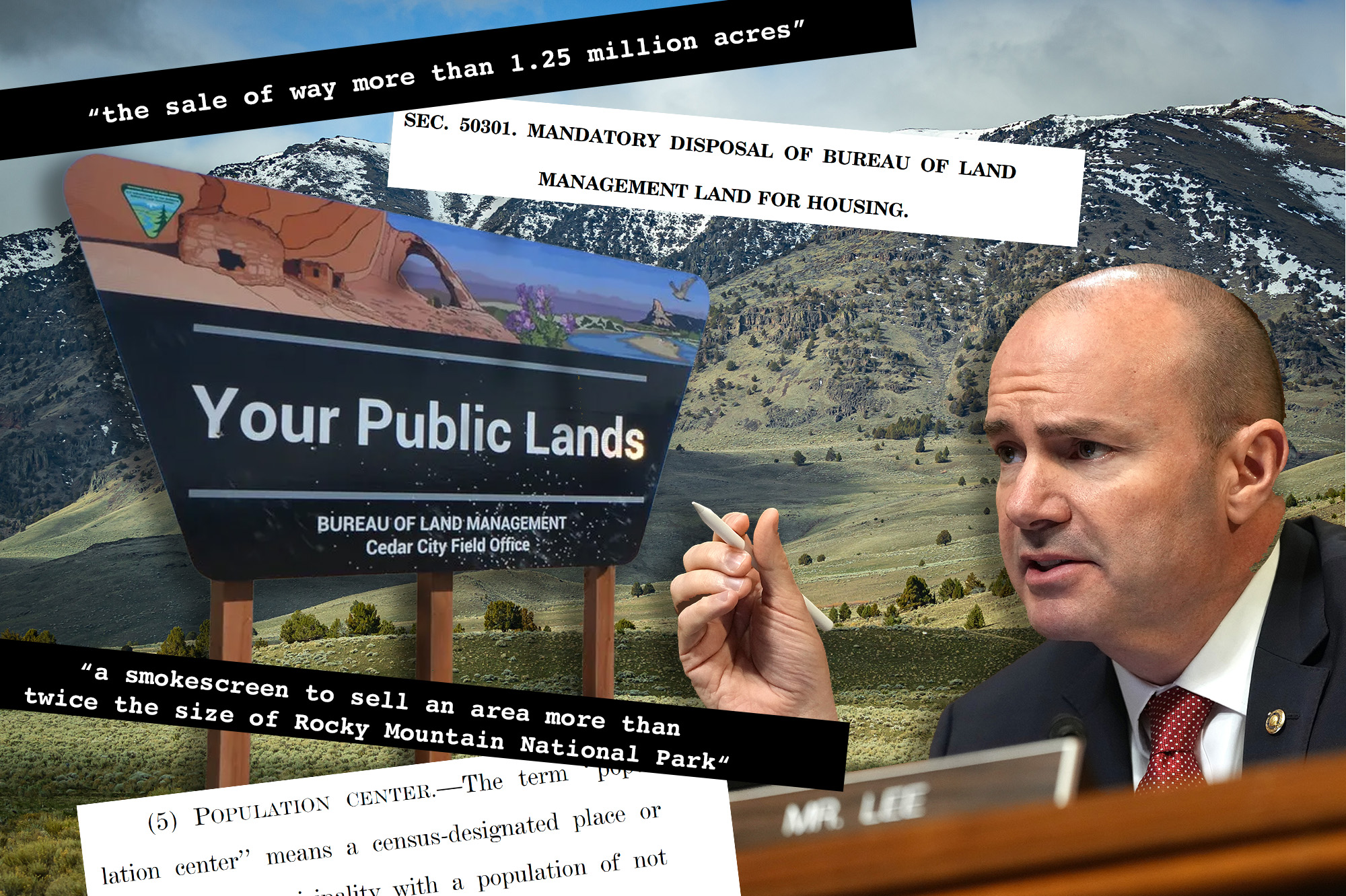

A Grizzly Stole My Client’s Elk, Then Treed Me for Seven Hours

This story, “Footrace with a Grizzly,” appeared in the May 1955 issue of Outdoor Life.

Two of my brothers, Gene and Wendell, and I had guided six elk hunters from Cleveland into the mountains 30 miles from our home ranch on the north fork of the Blackfoot, in western Montana. We were camped on Danaher Creek, at the head of the south fork of the Flathead. That’s prime game country. It was September, but snow had come early and the ground was still patched with it — enough for tracking. Prospects looked rosy.

Late the second afternoon one of the hunters killed a nice bull on Hay Creek, about 2 1/2 miles above camp. It was dark when he got in, but at daylight next morning I rode out with two packhorses — a grown elk is too much for one — to bring the kill down. We do so as soon as we can in this country, on account of bears. An elk or deer is likely to be half eaten overnight.

Bears are more plentiful and hungrier some years than others, and that fall of 1948 was a bad one. The berry crop failed completely and the bears were on the prowl day and night, hunting for anything that would fill an empty belly. So I wasn’t surprised to see bear sign several times as I rode up along the creek.

Half an hour from camp I hit a jackpine thicket that stopped the horses, so I tied all three of them and went on afoot to find the elk and pick a trail up to it. I hadn’t walked far when I crossed another fresh bear track. The farther I went the more sign I saw enough to convince me I’d be lucky to find the elk in one piece. I started to hurry, impatient to run the bear off and salvage what was left of the meat. But I was too late. When I got to the place where the bull had been dressed out I found only a few leavings and a broad trail where a bear had dragged the carcass off.

How would you feel if you’d outfitted a party of paying guests, herded them a hard day’s ride into the mountains with all their supplies and gear on pack animals, set up camp, and spotted the hunters in first-class game country, only to have a thieving bear lug off the first kill? Well, I felt the same way. I started out to find that elk and take it away from the bear.

I had hunted all my life and outfitted and guided for close to 20 years. With that much experience, I should have taken a second look at the bear tracks before I did anything else. But I was mad as a bee in a raided hive, and I overlooked that little detail. The sign I’d seen farther down the creek had been made by a black bear and I took for granted that this was one of the same breed.

I knew he was big, though, for the elk he’d dragged off would have dressed close to 400 pounds. But that’s all I noticed, and I’ve asked myself plenty of times since how fool-careless a man can get. The answer came too late to do me any good.

The trail was easy to follow. He had taken the elk up and around the side of the mountain, and he’d made easy work of it. After 300 yards or so the track dropped into a series of deep washes and then angled up a steep slope toward an isolated stand of thick spruce, just the spot for him to stop and cash in on his night’s work. I’d find him in there somewhere, with what was left of his loot. That likely wouldn’t be enough to pack out, I decided, getting madder by the minute.

I halted at the edge of the timber and went down on one knee for a look. Twenty-five feet uphill from me a patch of dark fur moved behind a log, and then I made out the outline of an ear and saw an eye staring in my direction. He had seen me first.

The rifle I was carrying was mighty light for the job. Many years ago, as a kid, I shot a box of 8 mm. shells at a coyote about 1,000 yards off. I didn’t kill the coyote, but the big rifle battered my shoulder so that I still flinch with any gun that slams back at me. Consequently I tote a little .25/35. I know it sounds screwy for a man in my business, but I do better with it than with the big bruisers.

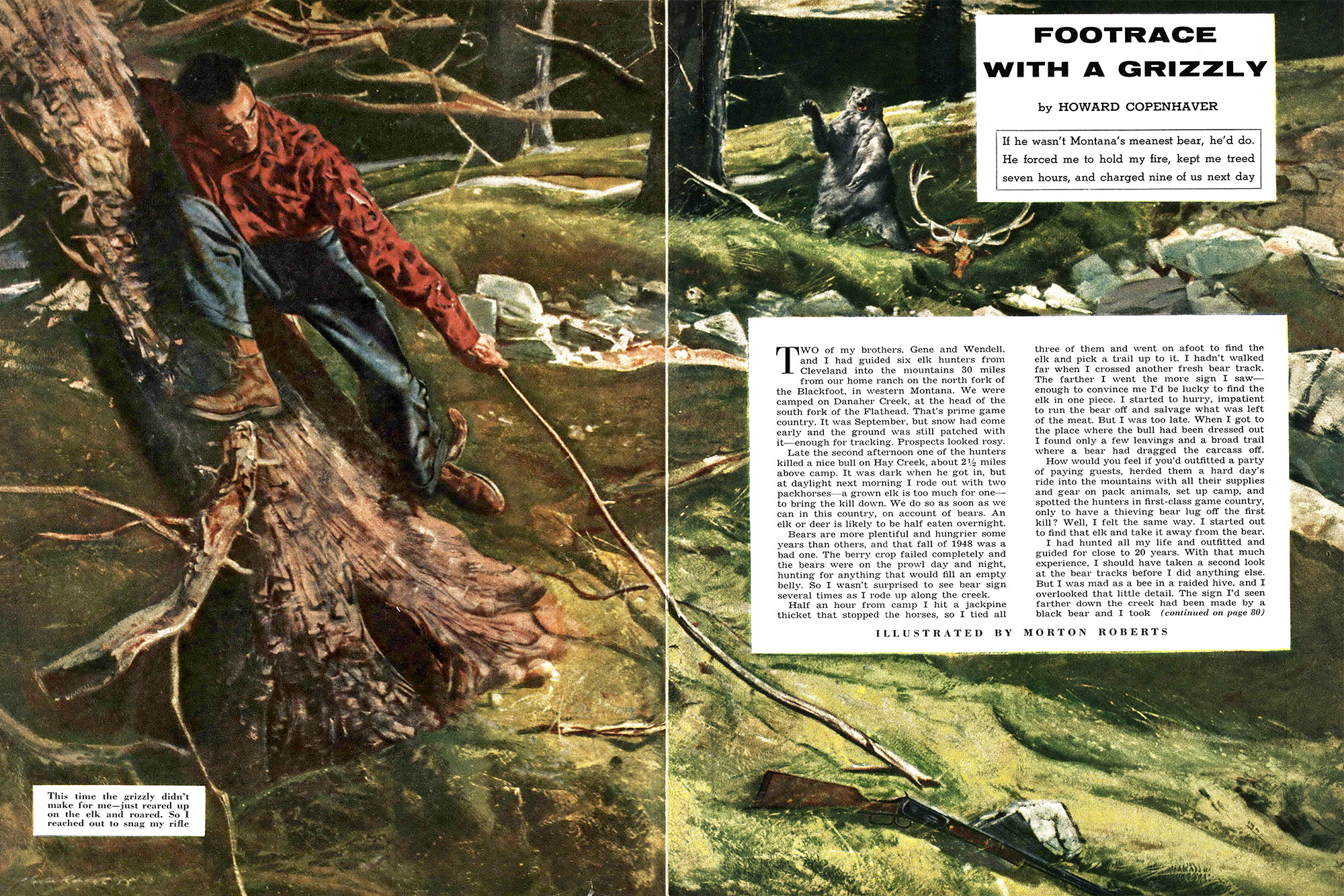

It wasn’t rifle enough for a big bear, even a black, but I figured if I hit him at the butt of an ear I wouldn’t have any trouble. He had the ear conveniently exposed over the log and I was so close I couldn’t miss. I brought the rifle up, slow and easy — and in the same instant the bear came up, fast and hard. He reared on his hind legs at my first movement and let go a roar that was enough to knock my hat off.

That roar changed the whole situation. I knew at last, a little late, that I wasn’t dealing with a black. I had walked into a grizzly as short-tempered as a stick of dynamite, and all of a sudden the little .25/35 seemed useless as a popgun.

We looked each other over for 10 seconds that seemed like a quarter of an hour. I don’t know what the grizzly thought of me but I had time to realize that he was a handsome old sorehead. His dark silvertip coat shone like frost, even in the dim light under the spruces. I held the gun on his neck and waited for him to make the next move, hoping it wouldn’t be in my direction.

When he did nothing, I took a cautious step back, and then another. He stayed put and I kept backing up until I had a reasonable distance between us. Then I dropped down into one of the washes and got out of there fast. But I still didn’t intend to lead the packhorses back to camp empty, and I knew I’d have to kill the bear if I wanted to claim the elk.

I decided to come at him from above and try a shot in the open, at something more than 25 feet. I made a big circle and worked warily down the hillside to the upper edge of the spruce thicket. I thought I knew exactly where I’d find him. He’d be on the elk, waiting for me. But I guessed wrong.

I was down on one knee again, trying to see under the branches, when he cut loose with another roar so close behind me that I thought he must be looking over my shoulder. I spun around and stared him in the face — just six yards off.

He wasn’t a pleasant sight. He was up on his hind feet like a man, eyes blazing, lips curled in a rumbling growl, the hair on his neck and shoulders all standing the wrong way. He looked 20 feet tall and he scared hell out of me!

How he got that close without giving himself away I’ll never know. We went back the next day, when the affair was buttoned up, to look over the sign an-d piece the story together. He had come out of the thicket on the downhill side, picked up my track and trailed me as a hound trails a rabbit, following me while I circled to get above him, stalking me with the stealth of a cat.

The snow was frozen and as crunchy as breakfast cereal, yet he’d crept to within 18 feet of me — we later measured the distance between our tracks with a steel tape — without a whisper of sound. Then he stood up and bawled his blood-chilling challenge, ready for the final rush. They say an unwounded bear won’t stalk a man, but this one certainly did.

I’d never stop him before he got to me with the .25/35 and I knew it. He’d be on top of me before that little bullet took effect. There was only one way out. If I could find a tree and reach it in time, I’d climb. A grizzly can’t follow you into a tree.

It was a thin chance, for there was just one tree of the right size anywhere near, and it was between me and the bear. When we paced it the next forenoon we found I was 10 feet from the tree and he was eight. But I didn’t have time to think. I must have acted from instinct, or maybe it was something they had drilled into me in the Navy, that a surprise offense is often the best defense. I yelled in his face, a screech that would have done credit to a Blackfoot buck, and jumped for the tree.

How I made it, slamming into him that way, I still can’t figure. My yell must have startled him for a second or two, and my headlong rush kept him off balance just long enough. I was in the tree when he started for me and out of reach when he arrived. I’ve been asked quite a few times since whether I had any trouble reaching the first limb. For the record, I never touched it. My first jump put me in reach of the third or fourth limb up. I didn’t climb. I sailed into that tree like a flying squirrel.

When I started my dash, I had it in mind to take my rifle with me, but when I reached a safe perch 15 or 20 feet off the ground I didn’t have the gun. I looked down and saw it lying two or three yards from the base of the tree, with the bear smelling and cuffing at it.

The grizzly really blew his cork over my get-away. He danced around under me, bawling and raging and clawing bark, tearing up the ground like a baited bull. I could see the elk carcass in the spruce thicket, about 20 yards away, and I kept hoping the fresh meat would lure him off. Finally it did. He turned and lumbered downhill, stopping every few steps to throw back a warning growl. When he reached the elk he lay down on it, but kept his head turned my way.

The first thing I wanted was my rifle. It still lay a few steps from the trunk of the tree. I gave the bear 15 minutes to settle down and get interested in the elk. Then I started inching toward the ground, lowering myself from one branch to another.

I was careful not to make any commotion, and he paid no attention until I was almost down. Then he seemed to realize all of a sudden what was going on. He lurched to his feet with a bawl of pure hate and came streaking uphill. A bear can cover ground fast for a short distance when he wants to, and I had to hustle to climb out of reach again. He trampled around under me for a while, grumbling and snarling, and then went back to the elk.

I gave him time to lose interest in me and tried another catfooted descent. It brought the same result. He let me get down to the lowest branches, then bounced up and came raging for me.

Read Next

It’s hard to believe, but we kept up that game at intervals for more than seven hours, from 8:30 in the morning, when he treed me, until almost 4 p.m. I have no idea how many times I went up and down the tree, but I was worn to a frazzle and realized I couldn’t keep at it much longer. Unless I got the rifle on the next try or two I’d have to give it up. And that meant sitting in the tree and waiting for help to come from ca mp, something I didn’t relish in the least. Gene and Wendell wouldn’t start to look for me until dark, and this bear was nothing to blunder into at night. I wanted to save them from that if I could.

But now the grizzly’s attitude changed unexpectedly. I suppose he finally decided that he couldn’t catch me in the tree and that I wasn’t going to risk coming all the way down. When I started down this time he lay on the elk and watched me balefully, growling and blustering. As I reached the lowest branches he stood up and bawled his resentment, but he refused to be tricked into making any more runs uphill unless there was a fair chance of getting at me.

That gave me the opportunity I’d been waiting for all day. I braced myself at my own height from the ground, with my legs tense and ready for a fast ascent. Cautiously I broke off a forked branch, reached out with it and snagged the rifle. Then I pulled it up to me. I felt almost secure as I started back up the tree with the gun.

But back on my perch I began to question my idea of using this peashooter on the grizzly, even shooting from the tree. There was only the slimmest possibility that I could kill him with one shot, and once he was hit and went into the thick spruce I wouldn’t have a second chance. I had Wendell and Gene to think about. They’d come up along the creek hunting for me. If I wounded this bear he’d likely jump them in the dark and kill one or both of them. He might anyway. Somehow I had to get out of this fix and head them off while it was still daylight.

As I let myself down to the lowest branches the grizzly growled ominously, and it took all the nerve I had to let go and drop to the ground.

I suppose I had looked over the hillside a hundred times, but now I took another look and thought I saw a way of escape. As near as I could figure, it was about 60 feet downhill to the elk carcass where the bear lay. Thirty feet the other way, uphill, was a tree I could climb. Beyond that were two more, a little farther apart. With a series of dashes and climbs, I might put enough distance between me and the grizzly for him to forget about me.

The run to the first tree would be risky but it seemed the only way out. I’d have 30 feet to cover while the bear was coming 90. If I could get a running start, I figured I could make it.

As I let myself down to the lowest branches the grizzly growled ominously, and it took all the nerve I had to let go and drop to the ground. I lit running. I heard a gruff bawl as the bear lumbered to his feet and then I could hear him pounding uphill behind me. But my 20-yard headstart was too much for him. I was up the second tree when he got there and I still had my rifle.

He snorted and tore around at the foot of the tree for a few minutes, then gave up and went back to the elk.

The next tree was about 50 feet farther uphill. As soon as he quieted down I dropped and went for it. It was easier this time. He came charging after me, but he had too far to run now to cause me much concern. Nevertheless, it took four trees and a total gain of 75 yards to make him call quits. He chased me up those four, one after another. Then he must have concluded that he’d driven me off at last, for when I came down the fourth time he paid no attention.

I backed away a few yards, one step at a time, to make sure. When he stayed put I took off uphill, watching him over my shoulder. I made a wide circle to get back to the horses, and you can bet your bottom dollar I kept my eyes open all the way to camp.

It was dark when I rode in. I had expected my long absence to cause some anxiety, but my story was greeted with more amusement than sympathy, to my annoyance, and it took my brothers and the rest of the party a couple of hours to realize that I wasn’t just spinning a tall yarn. It was hard for them to believe that a bear would keep a man in a tree a whole day. I finally convinced them, however, and before we turned in we had everything arranged to settle the grizzly’ s hash first thing in the morning.

“If he’s still there,” somebody put in.

“He’ll be there,” I predicted grimly. “He won’t go 10 yards as long as there’s a mouthful of that elk left. He won’t move unless we move him.”

We left camp at sunrise, following Hay Creek for a couple of miles, then riding straight up the mountain to get around the bear. I remembered an open ridge about 250 yards above him that would give us a clear view of the creek bottom, the hillside, and the spruce thicket where he was holed up. We’d post the hunters along that ridge and Gene, Wendell, and I would move down to flush him out. That way there’d be no chance that he’d catch us with our guard down, as he’d caught me the morning before.

It was a good plan and it might have worked, except for one thing we hadn’t figured on. Nobody needed to go into the brush and stir that bear up. He was ready to come out without any prodding.

We tied the horses a safe distance back in the timber and moved down to the ridge afoot. Most of our horses will bolt at grizzly sign in a trail, and we knew we’d be asking for trouble if we took them anywhere near the bear. We bunched on the ridge 300 yards from his thicket, directing the hunters to their places. The bear was nowhere in sight but it was a safe bet that he was down there watching us, because all of a sudden we heard a commotion on the hill below and Gene yelled ”Here he comes!”

I guess that was the first time my brothers had really believed me, too, for Wendell added “By gorry, it IS a bear!”

The grizzly boiled out of the thicket and came plowing uphill at a dead run, ready to tackle all nine of us. We let him come to see if he really intended to go through with it. After his first 40-yard dash he reared up on a fallen log, stretching high on his hind legs for a better look. I don’t believe it was caution that stopped him. We all agreed later that he just wanted to size us up before he took us on. We’ll never be sure, for we didn’t wait any longer. Gene got in the first shot. He belted the bear in the shoulder with a 180- grain Core-Lokt bullet from his .30/06 and the grizzly dropped off the log with a bellow that shook the ground. But he didn’t go down. He whipped around, bit at his shoulder, pulled himself together, and came pelting uphill straight at us.

The mountain fell in on him then. I don’t remember all the details, for there was yelling and shooting all around me. Not all the shots connected, for I saw twigs clipped off and snow and dirt kicked up behind him and on both sides. But I also saw three or four solid hits.

He kept his footing through the whole barrage but he knew he was licked. He wheeled and started the other way, still roaring, and Wen dell spiked him with a soft-nose in the back of the head. He was less than 100 yards from us when he went down.

When we skinned him we found he’d been hit nine times, and any one of them would have killed him, eventually. Yet he had stayed on his feet until that last shot blew his brain apart. I was glad I hadn’t tried for him with the .25/35 the day before.

Read Next: When Grizzlies Rule California

His pelt squared nine feet, as beautiful a silvertip skin as I’ve ever seen. It makes a fine trophy on our ranchhouse wall. My brothers and I estimated his weight at not less than 800 pounds. Some of the guests who had hunted Alaska browns thought he’d weigh more than that. Anyway, this is for sure: No meaner grizzly than that one ever roamed the mountains of Montana!

As for the elk, we salvaged part of it after all. Luckily, a bear begins at the neck and eats back toward the hams. covering his kill with brush and leaves and lying on it between meals. Unless he’s driven off, he won’t leave until the last bite is gone. This fellow had worked back as far as the loins. I figure he was saving the steaks for a last supper, but we didn’t give him time to enjoy it. The hindquarter were still in fine shape and we packed them out.

Read the full article here