Paul Newman, the Pacific and the bomb that changed the world

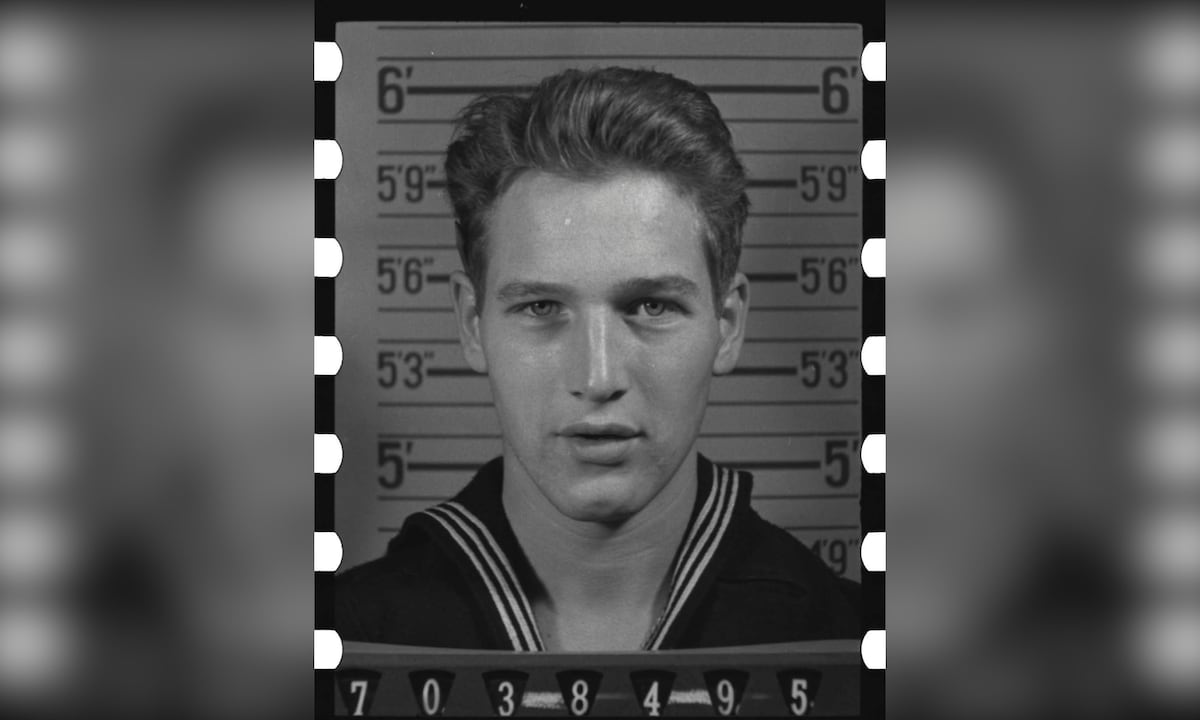

On Aug. 6, 1945, a 19-year-old U.S. sailor was serving aboard the aircraft carrier Hollandia about 500 miles off the coast of Japan when he learned the U.S. had just obliterated Hiroshima with a new “super-weapon” — an atomic bomb with the force of 20,000 tons of TNT. A more powerful bomb was dropped at Nagasaki three days later.

There is no record of what the aviation radioman third class said or thought when he heard the news, though he likely exhaled a sigh of relief. That seaman, along with millions of men preparing for the invasion of Japan, hoped the bombs would spare more lives by bringing an end to World War II, the bloodiest conflict in history.

Years later, the sailor — who went on to fame as celebrated actor Paul Newman — would reflect on that experience. Even though Newman later advocated for nuclear disarmament, he was thankful for the atomic bombs because he was certain he would not survive the amphibious landings on the Japanese home islands planned for later that year.

“Paul was a radioman and rear gunner in a two-man fighter-bomber that was carrier based,” recalled close friend and historian Richard Rhodes, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1987 for the book “The Making of the Atomic Bomb.” “He was all over the place in the Pacific Theater and felt lucky to survive.”

Newman’s perilous path to World War II began Jan. 22, 1943, when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy — four days shy of his 18th birthday. He was sent to Yale University for the V-12 Officer Training Program where he hoped to become a pilot, but washed out when his piercing blue eyes couldn’t pass the color-blindness test (Newman later admitted he also couldn’t do the “science” needed to fly airplanes).

However, the future actor qualified for torpedo bombers and flew in a Grumman TBF Avenger with Torpedo Squadron 84. His unit was assigned to the aircraft carrier Bunker Hill, but he never made it to the carrier because his pilot had been grounded with an ear infection.

That turned out to be a stroke of fortune. On May 11, 1945, at the Battle of Okinawa, the ship was struck by two kamikazes in quick succession, causing extensive damage and killing 396 men, including members of his squadron.

All told, the bloody fight for Okinawa cost more than 12,000 U.S. lives, including 5,000 sailors. The battle signaled a change in defensive strategies, clearly demonstrating how Japan was determined to extend the war by inflicting massive Allied casualties with fight-to-the-death tactics. The war in the Pacific was evolving into a grisly slugfest of attrition with no end in sight.

“Now that the Japanese were defending their home islands, they had beach defenses and short flights for kamikazes, along with suicide missions by midget submarines, frogmen and more,” said retired Rear Adm. Samuel J. Cox, director of Naval History and Heritage Command and curator of the Navy. “They even had civilians ready to fight with sharpened sticks. The Japanese military was prepared to sacrifice the whole country.”

Operation Downfall was set to begin Nov. 1, 1945, with 700,000 American Marines and soldiers, along with British and Commonwealth forces, landing at Kyushu, the third largest Japanese island. The U.S. Navy would support the invasion with more than 3,000 ships while the U.S. Army Air Forces would fly cover with nearly 3,000 fighters and bombers.

Because of the fierce resistance at Okinawa, American military planners estimated that conquering Japan would result in 1 million-plus casualties for the United States. Newman was convinced he would not live through the battle. Some projections estimated Japanese losses to exceed 20 million.

“The U.S. numbers might have been conservative,” Cox said. “The Allies didn’t know it at the time, but the Japanese had correctly guessed where the landings would take place and had moved more than 900,000 men there.”

President Harry Truman worried that the invasion — the largest amphibious assault ever planned — would result in too many deaths. The decision was made to use the atomic bombs and hope Japan would surrender.

“Truman did not want a repeat of Okinawa,” Cox said. “A blockade was already underway, but the prospect of starving 100 million Japanese to death wasn’t appealing. The atomic bombs, along with the Soviets entering the war against Japan, convinced the enemy to surrender.”

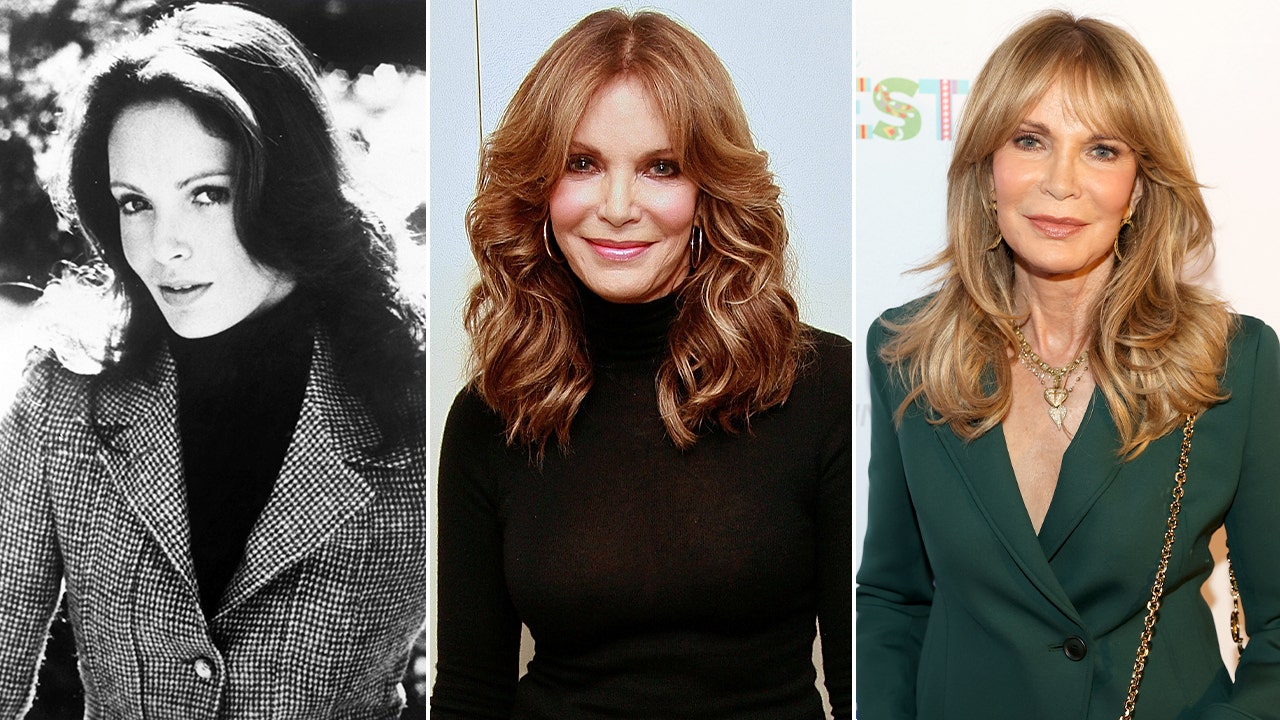

On Sept. 2, 1945, Japanese leaders signed the instrument of surrender aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Newman was soon on his way back to the U.S., where he went to college under the GI Bill and got bit by the acting bug. He began appearing on stage and in TV shows and movies, including his breakthrough role as boxer Rocky Graziano in the film “Somebody Up There Likes Me” in 1956.

Newman continued to garner acclaim and Academy Award nominations for such films as “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “The Hustler,” “Cool Hand Luke,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” “The Sting” and others. He earned the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1986 for “The Color of Money.”

For the 1989 movie “Fat Man and Little Boy,” Newman agreed to portray Col. Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army, who oversaw the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb.

For that role, Newman sought out Rhodes. He wanted insight into portraying Groves, so he met with the historian to find out what he had learned in writing his bestselling book about building the bomb. That initial interview blossomed into a mutual affection that endured for years.

“It was a nice, quiet friendship,” he recalled, adding, “He was a sweet man.”

When their schedules permitted, they met for dinners and drinks. It was during one of those private meals when the subject of World War II came up. When asked about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Newman was forthright in his answer, Rhodes recalled.

“I remember him telling me that he had been over there and specifically that he was training for the invasion of Japan,” Rhodes said. “I was talking about the deep complexity of using the bomb, how people had such mixed feelings. That’s when he said, ‘You know, Dick, I’m one of those guys who said thank God for the atomic bomb.’ He was training for an invasion that was going to be horrible and bloody and he would be damn lucky if he got out of it with his life.”

Rhodes was somewhat surprised by the answer, given that he knew Newman was active in the movement to end the proliferation of nuclear weapons and had even served as a U.S. delegate at a United Nations disarmament conference. Still, he understood what his friend was saying.

“You have to remember, we were really angry at the Japanese,” said Rhodes, who was 8 years old when the war ended in 1945. “They wouldn’t surrender. We knew they were defeated. We had destroyed their navy, we had destroyed their air force. Effectively, their people were starving.”

Rhodes and Newman continued to be friends long after the movie. Sometimes with their families, they would get together for movie premieres, at racetracks (Newman was an avid race car enthusiast and even competed in races) and the Hole In The Wall Gang Camp, a program for children and their families coping with chronic illnesses established by the Newman’s Own Foundation.

The last time Rhodes saw his friend was in 2008, just before Newman’s death from cancer. They had lunch together at the actor’s penthouse in New York City.

“I understood that he was seriously ill,” the historian remembered. “I had the chance to say to him, ‘Paul, I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I just want you to know this has been a wonderful friendship.’

“He looked at me and said, ‘For me, too.’ I get chills just reciting that story.”

Read the full article here