Hidden toll of brain trauma on naval aviators

Flying a fighter jet is often compared to being in a car crash over and over again.

Retired Navy F/A-18 Hornet pilot Matthew “Whiz” Buckley, a TOPGUN graduate and former instructor, remembers being hurled off the deck of an aircraft carrier at 150 to 200 miles-per-hour in less than two seconds.

Every catapult launch, every high-G turn, felt like an assault on the body and the brain.

Arrested landings were even more violent. Pilots, including Buckley, described them as controlled crashes: going from 150 miles-per-hour or more to a complete stop in approximately one second.

Strapped into the seat, the body could be restrained, but nothing stopped the head from snapping forward. Those forces were repeated daily, sometimes multiple times.

On deployments, pilots typically logged one to two arrested landings a day, one former aircraft carrier captain told Military Times on the condition of anonymity. Over a cruise, a junior aviator could expect to reach one hundred arrested landings. Mid-grade officers often doubled or tripled that number, with three hundred or more over the course of a career.

In naval aviation, those numbers were more than milestones. They were markers of credibility, proof of experience and proficiency.

Pilots knew their records were scrutinized by senior officers and by peers, the former captain said. Achieving higher totals meant not only a stronger professional reputation but better chances at advancement and post-Navy airline careers.

The culture created constant pressure to fly as much as possible, regardless of the physical toll.

Buckley flew 44 combat sorties over Iraq and spent years at the pinnacle of naval aviation. He loved every moment in the cockpit. But like many of his peers, he now says he lives with the hidden cost of flying: lingering brain trauma that no one in the Navy warned him about.

That silence is now drawing national scrutiny. The House Oversight Committee has launched an investigation into whether the Navy ignored evidence of widespread traumatic brain injuries among aviators.

Lawmakers want to know why no comprehensive study has been conducted and why projects like the little-known “Odin’s Eye” — an internal Navy project to evaluate the physiological and psychological effects inflicted on TOPGUN trainees — were kept in the shadows.

For pilots who spent years strapping into multi million-dollar aircraft and being blasted into the sky, the questions feel long overdue.

A culture of silence

The silence begins in the cockpit. Pilots are trained to push through discomfort and never admit weakness. In naval aviation, Buckley said, honesty with a flight surgeon can mean the end of a career.

“You tell a doctor you’re dizzy, you’ve got memory problems, or you’re not sleeping? You stop flying,” he said. “That’s why so many of us kept quiet. We wanted to stay in the air.”

The pressure is not just personal. Naval aviators live in a dog-eat-dog environment where racking up landings, missions and qualifications determines who advances. Buckley said the culture emphasizes toughness and perfection, yet discourages transparency about physical or mental challenges.

The result is that repeated head and neck trauma, suffered in silence, accumulates over years of service.

Dr. Robert Cantu, one of the world’s leading experts on concussion and co-founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, has spent decades studying brain injuries in athletes. What pilots endure is comparable and possibly worse, he said.

“In football or hockey, we see how repeated sub-concussive hits cause inflammation, axonal injury, and in some cases chronic traumatic encephalopathy,” Cantu explained. “Pilots may not get tackled every Sunday, but every catapult launch, every high-G maneuver, every landing is stress on the brain. Over years, it adds up.”

Cantu pointed to reforms in professional sports as examples of what the Navy has yet to adopt. The NFL and NCAA introduced baseline testing, limits on full-contact practices and protocols for removing players showing concussion symptoms. Combat sports like the UFC have implemented stricter medical checks and suspensions after knockouts.

These measures followed years of denial, lawsuits, and public outcry.

“We learned the hard way in sports,” Cantu said. “Denial only delays the damage.”

What remains difficult to measure in aviation is the toll of sub-concussive events. A football player might suffer a handful of hard hits in a game, but a naval aviator is subjected to rapid acceleration and deceleration every time he or she launches or lands.

Arrested landings on carriers, described by Buckley as “like a shot to the body,” occur multiple times a day in training cycles. Even when no concussion is diagnosed, the brain and neck endure jarring forces that, according to neurologists, can still inflict microscopic injuries over time.

A ‘moral obligation’ for TBI prevention

Engineering experts are exploring solutions. Dr. Bryan Pfister, chair of biomedical engineering at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, studies how blast waves and blunt trauma affect the brain. Technology already exists to better understand what happens inside a pilot’s head, he said.

“Sensors in helmets, neck collars, even cockpit design — these are all tools to measure and potentially reduce the risk,” he explained.

If those tools were adopted, the Navy could collect real-time data about the stresses pilots endure, instead of leaving questions unanswered.

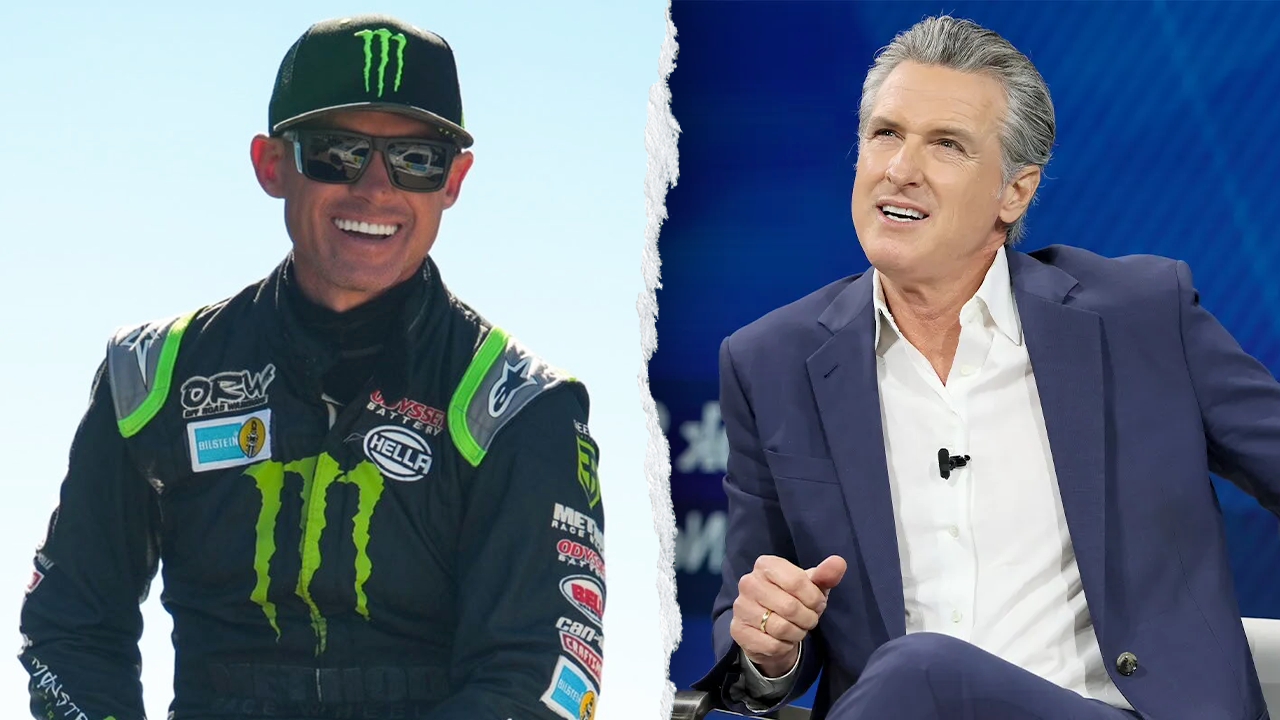

Other fields have already turned research into practical safety equipment. Dr. Tamara Reid Bush, professor of mechanical engineering at Michigan State University, has studied the Head and Neck Support device used in auto racing. The HANS device stabilizes the skull and spine during impact, dramatically reducing the risk of catastrophic head and neck injuries.

“In racing, we reduced catastrophic head and neck injuries by stabilizing the skull and spine during impact,” she said. “The principles could be adapted for pilots.”

Integrating such a device into aviation, however, would not be simple. Cockpit space, oxygen masks, ejection seat systems and helmets all create challenges that racing engineers do not face. Still, Bush sees promise in adapting cross-industry safety lessons for military aviation.

For now, naval aviators lack the kind of baseline testing and monitoring that athletes receive. They also lack the cultural permission to acknowledge symptoms.

Buckley remembers friends who suffered from memory loss, insomnia and mood swings but told no one for fear of being grounded. He has counted 16 friends lost in aviation mishaps and four to suicide. These are pilots who loved flying, who lived for it. Yet when the flights ended, they were left with unspoken damage —sometimes staring into the mirror at someone they no longer recognized.

Unlike professional athletes, who now have medical protocols and, in some cases, lifetime health monitoring, aviators transitioning to civilian life often find themselves isolated. Disclosure of mental health symptoms to FAA doctors can threaten their airline careers, creating another incentive for silence.

“We silence them into being perfect each step of the way,” Buckley said, “and at the end when they are done many are left with irreversible damage.”

The stakes extend beyond individual health. Naval aviation operates billion-dollar aircraft in complex, unforgiving environments. A football player’s concussion affects himself and his team. A fighter pilot’s momentary lapse could endanger an entire crew, an aircraft carrier or a mission.

Lawmakers are pressing for answers. House Oversight Committee Chair Rep. James Comer, R-Ky., and committee member Rep. William Timmons, R-S.C., have demanded the Navy provide studies, data and communications related to aviator health since 2023. They asked specifically about Project Odin’s Eye, an initiative reportedly aimed at studying brain trauma among pilots.

Their letters stress that aviators deserve transparency about the risks they face.

For Buckley, the answer is clear: The Navy must follow the lead of institutions that once resisted acknowledging brain injuries and are now working to protect their people.

The NFL and UFC once silenced athletes and are now investing heavily in research, protective gear and cultural change. Motorsports turned tragedy into reform with the HANS device. Naval aviators, Buckley argues, deserve the same commitment.

“Protecting aviators isn’t just about readiness,” Buckley said. “It’s a moral obligation. These men and women love flying enough to pay the price with their bodies. The least the Navy can do is protect them from avoidable harm.”

Read the full article here