Tracking Coyotes with Dogs and Snowshoes Is the Greatest Hunt of All Time

This story, “Littles Wolves,” first appeared in the Dec. 1967 issue of Outdoor Life.

One of the greatest game animals in the northern United States, and also one of the least appreciated and most lightly hunted, is a little wolf that rarely weighs more than 40 pounds.

It has an antifreeze coat, teeth sharper than grandma in the Little Red Riding Hood story, a body as lean as a greyhound’s and tougher than whang leather, and the spunk to lick four times his weight in dog meat any day.

I’m talking about the coyote, known also as the brush wolf, yodel dog, and — when it comes to stockmen — by quite a few less complimentary names.

Specifically, I’m talking about the coyote found along the south shore of Lake Superior in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where I have spent some of my best days hunting him, in swamps, on frozen rivers, in brush and timber, on bare hills, and even on snow-plowed highways. What I know about him I learned in that country, and all of it leads to one conclusion.

No animal I’ve ever hunted has a greater potential for furnishing fine sport. I love hunting of any kind — rabbits, birds, deer, bear, or moose (I have to go to Canada for moose) — but I rank the coyote right up with the best of them.

He offers rough and rugged action, and for any man who enjoys following hounds, he’s terrific. And there are enough of his kind, and they know enough about taking care of themselves, so there’s little danger the supply will ever fail. I can’t imagine hunting out a coyote population by fair means.

I rate the coyote about the most overlooked and neglected game animal in the Midwest. In my time I have known of only three or four families in northern Michigan who were consistent coyote hunters. They were also very enthusiastic about it.

Coyote hunting has another advantage. It’s available in January, February, and March, when seasons are closed on most game.

And if you can’t find a coyote track, in many places you can fall back on a fox or bobcat. Just being in the woods on snowshoes in late winter, and seeing the Christmas-card scenery, is half the enjoyment.

Read Next: A Crash Course in How to Hunt Coyotes

I was brought up on coyotes. My dad went into the Upper Peninsula with the logging camps as a young man, settled near the little town of Matchwood, east of Lake Gogebic, became a farmer and part-time logger, and was a fire towerman for Michigan’s conservation department for 17 years. He died in 1961 at 83. Dad was the best coyote hunter I have ever known, and it was bounty money that tided our family over the dark times of the depression in the 1930’s.

Dad had trapped coyotes as far back as I can remember, and I’m 45 now. In the winter of 1937, when I was 15, a neighbor family, the Coles, got together a pack of six good coyote hounds, and dad and my older brother Mike started hunting with them.

I went along on one of those hunts and got my first taste of coyote chasing. I had caught my first coyote in a trap three years before but had never shot one. On my first coyote hunt, a group of about 15 men surrounded an area. The dogs ran a big male coyote and caught up to him, but they couldn’t hold him. He tried to get through our line, and George Miller, a neighbor boy, killed him.

Not long after that, luck smiled on me. We put the dogs on a track behind our farm, and they finally stopped a brush wolf under a snow-covered leaning cedar on the West Branch of the Ontonagon River. We punched him out with a pole, and he ran my way. I downed him. The excitement and action got into my blood, and I was a coyote hunter from that day on.

Before that winter was over, dad and my brother, and Buddy and Walt Cole, divided into two teams; each team took three of the hounds, and the teams hunted coyotes for a living. The depression was at its worst by then, and there was no winter work, and no money to be earned any other way.

I went along on those hunts as often as school attendance permitted, which meant whenever good snow conditions jibed with a weekend.

We did pretty well, and the next fall dad got a pair of big Walker hounds of his own — Dewey and Sounder. They turned out as good as any dogs I have ever followed, and from then on the Livingstons were a coyote-hunting clan, for income and fun.

I have no use for bounty systems. Michigan poured almost $2-million down that drain in one 10-year period without any visible results. But I have to admit that bounty money saved the day for us back there in the black 30’s.

As the years passed and the economy improved, the bounty income became less important, and the fun took over. Dad kept those two hounds until I came home from World War II in the winter of 1946.

I killed a coyote ahead of old Sounder that February, after one of the longest and hardest chases I ever had. Sounder ran the wolf from shortly after daylight until just before dark. As far as I can remember, that was the last one he helped to account for.

When there was a bounty on coyotes, we hunted coyotes for a living. The depression was at its worst by then, and there was no winter work, and no money to be earned any other way.

I joined the Michigan conservation department as a conservation officer in 1947. For several years I was stationed at Watersmeet in the western part of the Upper Peninsula. That’s top coyote country, and my job and hobby coincided nicely.

I hunted the little wolves all winter whenever conditions were right. To help things along, for a few years I even took my annual vacations in January or February. But don’t get the idea that I made any high scores.

Coyote hunting is not that kind of sport. You go out only on the right kind of snow; you have to wear snowshoes; most days you walk your legs down to stubs; and if you take one coyote in a day, you’re doing very well. One winter I stretched 11 pelts; another year 18 — all hard-earned. Then there was a year when conditions were not so good and I took only eight on 22 hunts.

I’m forest-fire supervisor for the conservation department in Michigan’s southern region now, living at Lansing, the state capital. I like the job, and my wife Marie and our daughters Laurel and Kathy and Cheri like the advantages the city offers.

But there are no coyotes to hunt, and how I miss limbering up those special muscles that only snowshoeing calls into play whenever we get a good tracking snow.

Our son Mike is 15, and I miss the chance to break him in as a coyote hunter, too. He got his first gun, a Winchester .22 caliber, on his seventh birthday, killed a bear at 11, and shot his first deer when he was 14.

One of these winter weekends there’ll be a phone call from some friend up north who has good dogs, and Mike and I will head up I-75. Then I’ll initiate him into some of the most exciting hunting he’ll ever find in this part of the country.

There are two prime requirements for it, one about as important as the other. First, you must have the right kind of dogs. Second, both they and the men who follow them must be in excellent physical condition. I know of no game that puts the hunter and his hounds to a more rigorous test.

I have used all kinds of hounds — redbones, Walkers, black and tans, blueticks, and some that were a mixture. But the Walkers seem to have the biggest helping of the two basic requirements — staying power and the grit to do a lot of fighting — and my best hounds have been of that breed.

Coyote hounds do not need to kill, but they must have the guts to stop and hold, and all the Walkers I have owned qualified.

Coyote hunting in the Great Lakes States is done in deer country, and the dogs must be deerproof. But we never had any trouble on that score. We started our young hounds in areas away from deer yards until they learned what they were after, and we never turned them loose on a cold track. Instead, we kept them on leash until the coyote was jumped.

That way they soon learned what they were hunting, and once a hound makes up his own mind that he’s a coyote dog, it’s been my experience that he’ll follow a trail right through a deeryard without getting side-tracked.

Dad and my brothers and I always thought three dogs made the ideal pack, but much of the time we had only two. If they were good ones they did the job without any trouble.

Of course the more dogs you let go, the merrier the noise. But there’s also a disadvantage: you have more dogs to find when the hunt’s over.

I’ve never had much success finding a fresh coyote track by driving on roads after new snow as some hunters do. I’ve done most of my hunting in big chunks of roadless country. Unless an area is laced with roads, the little wolf is not inclined to cross them.

I like to take off on foot and lead my dogs. New snow is essential, and the best time to hunt is when a fresh fall — anything up to 10 inches — covers a foot or two of packed snow. That means good tracking, good running for the dogs, good conditions for snowshoeing. The better you know the area and the habits of its coyote population, the more likely you are to have luck. On your home ground you’ll probably have a pretty good idea of where they’ll be.

You may have heard them howling at night, or you may know where carrion is available — perhaps deer carcasses left in the woods from the hunting season. Coyotes rely heavily on such food and hang around as long as it lasts.

Once we hit a track, we lead the dogs until we jump the little wolf. That way we pit fresh hounds against a fresh wolf, and the dogs have one big advantage. He has to break trail for them.

The dogs run single file, and the hound in the lead has the hardest going. If the lead hound slows down ever so little, the next in line will plow past him and take the lead. When this hound tires — if there are three or more in the pack — another moves ahead.

Under the best of conditions, with nearly a foot of new snow over old, I’ve had my dogs catch and stop a coyote in six minutes. But that’s exceptional.

Far more often a chase lasts two or three hours. If the coyote is long-winded and can find good running, it may go through the day. And now and then the hounds won’t catch him even by dusk.

Far more often a chase lasts two or three hours. If the coyote is long-winded and can find good running, it may go through the day. And now and then the hounds won’t catch him even by dusk.

In roadless country, coyotes are not likely to circle. You have to rely on dogs with enough endurance to catch them, and that calls for a lot. You need a fair supply of endurance yourself, too. One winter, a partner and I hunted 34 days and tallied the number of miles we walked each day. It averaged 14.

Some of our hunts ended in less than five miles, but we finished others after midnight, mites from home or the place where we had left our car. Those are the days that separate the men from the boys — especially on snowshoes — if the snow happens to be soft and deep. In recent years, snowmobiles have become popular in coyote hunting. They cut down the leg work and improve the hunter’s chances, but I still feel the ideal way to go after the little wolf is on foot, pitting your legs and lungs against his, earning him if you take him.

One thing you can count on. If the coyote knows where there is good running, he’ll head for it. The wind-packed snow on frozen streams is a favorite, and he’ll even take to a plowed road and run it for miles if he needs to.

Hunting near a frozen river, we always put a man on the ice upstream and another downstream from where we expect the coyote to cross. We know he’ll be almost sure to take to the ice and run into one or the other of them.

I remember a coyote I killed back in the 1950’s that put on an outstanding plowed — road performance. We’d had fresh snow two nights in a row, and it was deep and light as feathers — hard going for all concerned.

One of my partners who did a lot of hunting with me at that time was Don Foster, a farmer who lived at Fairgrove, in the Thumb area of southern Michigan, almost 500 miles from my former home.

I had become acquainted with him when he came north to hunt deer. He was unmarried and had no ties, and that winter he brought his dogs to the Upper Peninsula for two or three months, cutting pulpwood for a living and hunting coyotes every chance he got.

This particular morning, he and my brother Mike — then sheriff of Ontonagon County — and I started out right after breakfast with my three Walker hounds, Duke, Goof, and Mitzi.

We walked about four miles and hit the track of three coyotes, but the tracks had drifted in with snow until we couldn’t tell which way the wolves had traveled.

We followed, and in a sheltered place where the tracks were clear we found a minor mystery: coyote tracks going in two directions. Two went one way and one another, yet apparently all were in the same pack.

None of us had ever seen anything like that, but after a little head-scratching we agreed the way to solve the riddle was to take the tracks of the two and hope for luck.

We walked another two hours and finally found where all three wolves fed on a dead doe and left. Shortly after that, the trail turned downwind, a good indication a coyote is about to bed down, and then, at the top of a knoll, we hit three hot beds and tracks leading away on the jump.

We unbuckled the collars, and the dogs lit out. They were plowing through almost a foot of snow, but we knew things were worse for the wolf than for them. The dogs were out of hearing in minutes, and we plodded off after them. The coyote the dogs were chasing needed better running conditions and he knew it. Within a mile he came to an old snowshoe trail, ran it for two miles, turned off, and followed the ice of a creek to the nearest farm road.

From then on he was a road wolf, and to hell with the consequences.

He took the farm road south for a mile to M-28, the paved highway running from Wakefield to Marquette, and turned east on the pavement.

A mile farther, a farmer’s dog ran out, and the coyote had to leave the highway. But the D.S.S.&A. Railroad tracks run beside the road there. He climbed through a woven-wire fence, took to the ties, and kept going.

That maneuver fooled our hounds, probably because the coyote had made a long jump from the plowed road to the top of the high snowbank alongside. We met the dogs coming back, and we collared them and followed the railroad tracks.

The coyote stayed on the railroad for another mile, left it, crossed M-28, circled a brush-bordered farm, came back to the pavement, and decided the pave-ment was best after all. He went east and ran through the little settlement of Matchwood without turning right or left, but nobody saw him.

At Matchwood we borrowed a car, loaded our hounds into it, and went after the coyote once more. He was tiring now and wouldn’t leave the plowed pavement for love or money.

The 1966 Buck Hat Is Here

Get Yours

His tracks showed where he had met cars, but he had merely crowded close to the snowbank and kept running. Later, we talked with farmers who had encountered him and paid no attention, thinking he was a stray dog.

Two miles east of Matchwood, he turned off on a farm road once more, ran along it a mile and a half, and finally took to the woods again.

We let the dogs go there, and around 4 p.m., almost seven hours after we had jumped him and 10 or 12 miles from where we had first hit his track and those of his two packmates, we caught him in a big open field.

He was headed for a farmer’s barnyard where he probably hoped to throw the hounds off by running among the cattle.

The coyote was so tired that after Mike put a limp in his gait with a long shot that nicked a front foot, Mike actually ran him down, and held him under a snowshoe.

The dogs closed in, and I finished him with a shot from the .22 Colt revolver I was carrying. When we looked him over, the riddle of the two-way tracks was solved. He had a broken hind leg, probably from a trap where he’d been caught years before.

The leg had healed and was about as good as the three others, but the foot was turned backward. For a wolf with that handicap, he had given a terrific account of himself.

Incidentally, I like a .22 sidearm or any small-caliber rifle for this hunting. You should use a light gun, easy to carry in brush, and you don’t need any-thing bigger. Most of the time you kill the coyote after the dogs have stopped him. Rarely do they drive him to you and give you a shot that would call for a shotgun or heavier rifle.

Mike was able to step on the road-runner with his snowshoe because the coyote was played out, and the snow was deep and light. I haven’t seen many coyotes I’d want to try that with.

I’ll never forget the hunter I once watched kick off his snowshoes and climb up on a brushpile under which a coyote had run.

He broke through, and the wolf grabbed his foot, bit through boot and heavy felt sock, and nipped the skin. The hunter came out of there as if the brush heap had caught fire.

Coyotes aren’t big, but in a scrap there’s a lot of ’em for what they weigh. The average weight of those we killed one winter was only 27 pounds, and the biggest I ever took weighed 44. In our country, any coyote that goes above 40 pounds is exceptional.

I’ve never seen a skinny one. All I have skinned have been in top condition. On the other hand, they don’t carry an ounce of excess fat. They’re all muscle, tough as whalebone.

They’re equipped with excellent eyes, ears, and nose. I rate them as the most cunning animal I know. You almost never see one unless dogs run him to you.

The black bear is no slouch at keeping out of sight, but I have seen many more bears than coyotes, except for those that my hounds brought to bay. The little wolf lives by his wits, with enemies everywhere he turns, but he thrives in spite of them.

He’s a highly successful hunter. His favorite winter food includes rabbits, mice, ruffed grouse, now and then a porcupine if times are hard, and dead deer. He takes live deer, too, if he needs to, but there is no evidence that under normal conditions he hurts a healthy deer herd.

Cornered, he has the sense to get into a hollow log, crawl under a windfall or brushpile, or take shelter in a log jam or beneath an overhanging shelf of ice along the bank 0f a river.

He wants to get his back end against something so that the clogs must come at him from the front. That way he’s ready to take care of them.

He’s hell-on-wheels in a fight, all out of proportion to his weight. His long, thick fur protects him, and he can cut the toughest hound to ribbons in jig time.

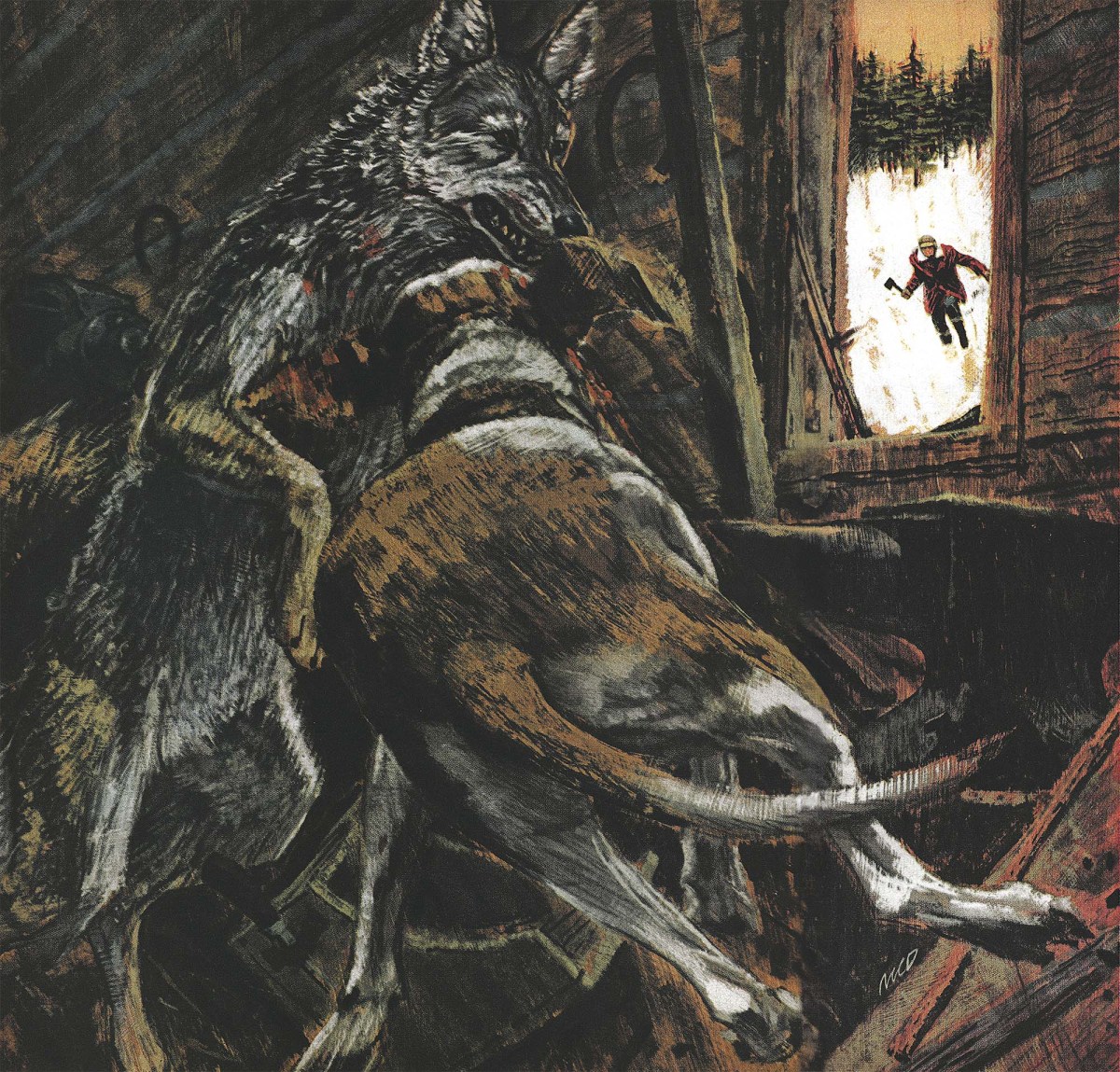

I’ll never forget what happened to King, one of the best dogs the Coles ever had. A coyote that he was after ran into an abandoned blacksmith shop and took refuge under an old wood work bench.

King had never met the brush wolf he feared. He dived after this one. The coyote came out, and my brother Mike killed it with his hand ax. But when King came out, one of his eyes was hanging on his cheek. He went blind in the other one and had to be retired from hunting.

With dogs driving a coyote, the little wolf’s mind is all on them. A man can stand right out in the open on a frozen river or in a clearing, and the wolf will run right up to him and not know he’s there.

But when a coyote is held at bay and a man walks up, the coyote watches the man.

He’ll go on snapping at the dogs, but his heart is no longer in the fight. He has a bigger worry now, something he fears much more than he does any hound.

The most unusual place I’ve ever known a coyote to make a stand provided a surprise and funny ending to a very long hunt. My partners that day were Dewey Wilbur, a neighbor at Watersmeet; and two men from Marquette, John Rossi and Ken Lowe.

Ken was editor and outdoor writer of the Marquette Mining Journal, and it was his first coyote hunt.

Dewey and I had killed a coyote the day before and had seen the tracks of others in the same area. It was a cold, clear March morning with perfect snow conditions, and we found a good track before we had walked an hour in the Michigan snow.

The track was very fresh, and we’d followed it less than a mile when I decided to let my three dogs go. I figured the wolf had half an hour’s start, but the dogs would cut that down in short order.

Another mile and we heard the far-off clamor of the hounds. They were swinging back toward the road where we had left our car. Their quarry was making a big circle, something a coyote doesn’t often do.

There was one thing I wasn’t quite sure of. I knew by the sign that this was a female coyote. If she happened to be in heat, not unlikely at that time of year, the dogs might not be as rough on her when they caught up as they’d need to be. I had seen that happen more than once.

In breeding season, if you jump a pair of coyotes, the hounds are almost sure to take the track of the female. But they don’t always fight her real hard.

When the dogs trail her, the male coyote proves he’s no knight in armor. He gets out of there right away.

This time the dogs went beyond hearing. We walked the track for six miles without hearing a single bawl.

“How long does this go on ?” Ken demanded. “These snowshoes of mine must be made of lead.”

“Oh, we’ll catch up any time,” Dewey Wilbur assured him.

“Sure, any time between now and dark,” grunted John Rossi, who hunted coyotes before. Another mile and we heard the far-off clamor of the hounds. They were swinging back toward the road where we had left our car. Their quarry was making a big circle, something a coyote doesn’t often do.

We had taken the track in midmorning, and we got back to the road two hours after noon. In four hours we had walked 10 miles, through scrub timber, spruce thickets, and alder swamps, over some of the roughest country in northern Michigan.

The dogs were yammering off to the west somewhere, barely within hearing. From the racket, I judged that the chase had turned into a running fight and that they were not giving Miss Coyote quite the treatment to stop and hold her.

“I guess love can be stronger than hunting blood at this time of year,” I told my partners.

Then the uproar changed to the sharper, angry sounds of battle, and I knew she was finally cornered. We pulled off our snowshoes and trudged down the plowed highway, between head-high snowbanks.

The noise of the scrap became louder. We topped the crest of a low hill, and there to our amazement were the three hounds, worrying and barking around our car where we had parked it at the roadside that morning.

They had run the coyote under it, something I’d never seen happen in all the years I had hunted. The coyote could hardly have picked a better place for our benefit.

We could see as we walked up that the dogs didn’t have their hearts in the job. But once we got there Duke remembered that he was a coyote hound after all, and romance be damned!

He dived under the car, grabbed a mouthful of wolf fur, and yanked her out. She came out fighting, and the two other dogs pitched in. I was carrying a Colt .38 Special that day, and the instant there was an opening, I put an end to the fracas.

Ken Lowe leaned on his snowshoes, shaking his head.

Read Next: The Best Coyote Calibers

“Of all the lousy tricks,” he growled. “Lead us all over the devil’s half-acre in this snow, and then come back and hide under our car!”

Dewey Wilbur gave him a cheerful grin.

“That,” Dewey told Ken, “is coyote hunting.”

Read the full article here