The Legend of Old Crooked Horn, “the Biggest Buck In Utah”

This story “Old Crooked Horn” was originally published in the September 1982 issue of Outdoor Life.

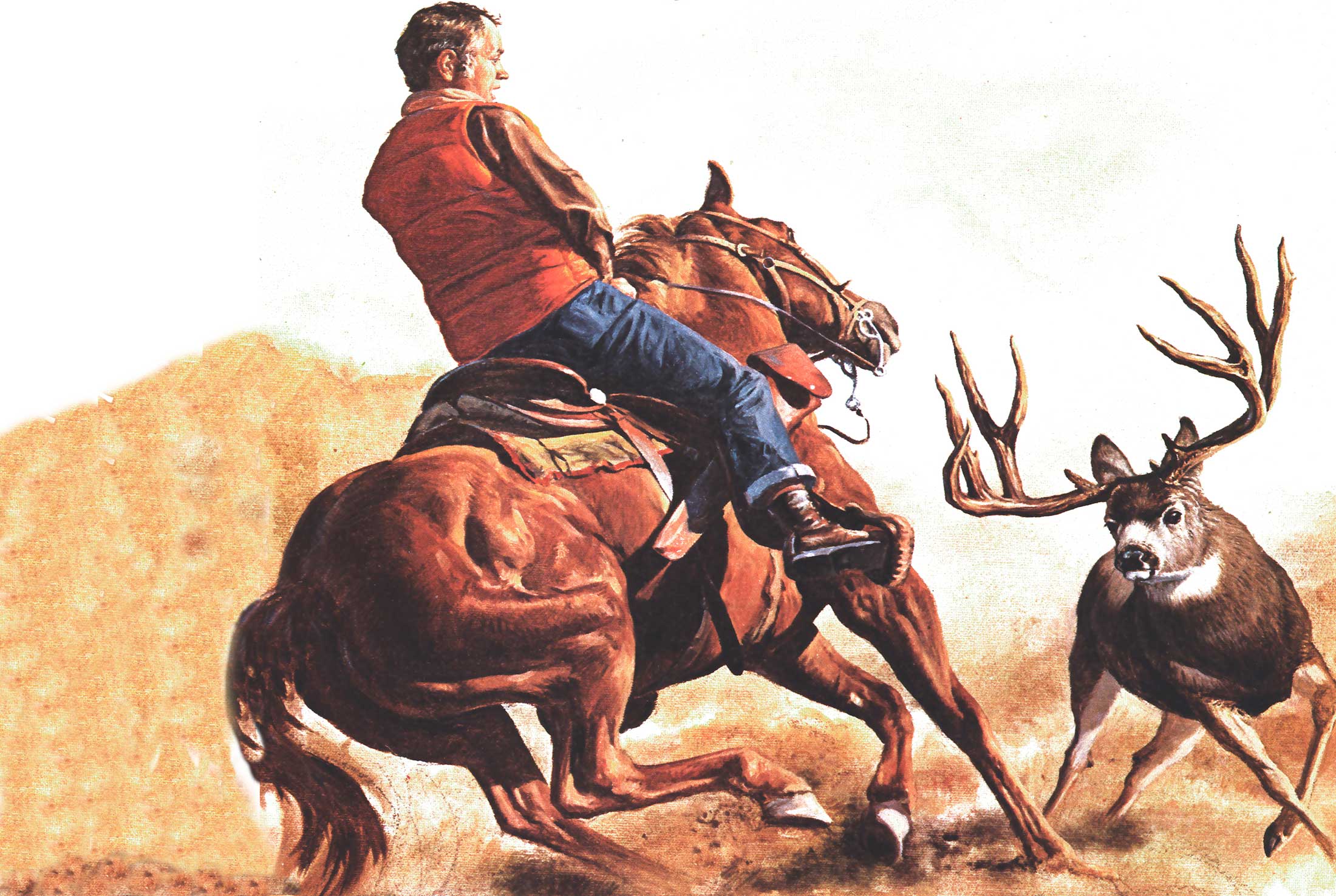

The big mule deer buck was mad. He wheeled, lowered his head and charged Vaughn Wilkins, who was atop a green broke colt.

The sight of that big, mean buck crashing head-on toward Vaughn was more than his nervous colt could stand. Vaughn was plumb scared, too. The big buck we called Crooked Horn knocked sunflowers every which way as he came flying along.

The colt spun around and bolted, and I don’t think Vaughn tried too hard to stop him. The buck kept up the attack and chased Vaughn and his colt into thick timber at the edge of the patch. Finally Crooked Horn backed off and disappeared into the brush.

It was opening morning of Utah’s deer season. Nine of us had just ridden horseback through the sunflower patch where we knew Crooked Horn hung out. We saw his fresh tracks but couldn’t jump him. That’s when Vaughn volunteered to really bust up the sunflower patch on his colt.

We were pretty confident the buck was in the area, because he laid claim to the 300-acre abandoned farm field about a month before the season. I had seen him several times in the area, and I couldn’t wait for deer season to open.

Vaughn’s strategy was simple. We would scatter outside the tall sunflowers and take up positions while he tried to jump the wary buck. He left his gun with one of the boys because he couldn’t shoot off his green broke colt, and if he dismounted quickly, he wouldn’t be able to see the buck because of the high sunflowers.

As luck would have it, Vaughn jumped Crooked Horn far up the patch and out of our sight. The chase was on as Vaughn scrambled after the buck, trying to haze him down the fieId toward us. Finally, Crooked Horn had been crowded too close by Vaughn and his colt. The deer made a quick 180-tum and headed straight for the startled horse and rider.

The drama was over by the time we rode up the field, except for the dust that was still billowing around. Vaughn was walking through the weeds, looking for his hat that had flown off during the melee.

”You missed quite a ride,” Vaughn said. “If I was in a rodeo, I’d have won top prize. No way was I going to leave that saddle while that crazy buck was around.”

“Too bad you didn’t have your rifle,” someone said.

“Yeah,” Vaughn answered. “That buck was so close he’d of had powder bums if I could’ve hit him from that buckin’ colt.”

Vaughn found his hat, beat the dust off it and climbed back on his horse, still shaking his head in disbelief.

We combed the sunflowers the rest of the day, but couldn’t tum up the buck. The story was the same the rest of the season. We hunted hard and long, but couldn’t find a trace of him. He simply disappeared.

Two days after the season ended, I saw Crooked Horn back in the sunflower patch. The big deer grazed along as if he knew he was safe. For the time being, he was, but I’d be after him next year.

The first time I ever laid eyes on Crooked Horn, he was drinking from a sandbar along the Green River in late summer of 1959. One of his antlers had a natural five-point spread, but the other grew straight sideways from his head at a 90° angle. It was about 35 inches long and had five points sticking out at regular intervals. Because the horn was so freakish, I judged the outside spread to be more than 45 inches.

I should explain my credentials to have estimated the buck’s antlers at such an impressive width. I was born and raised on a ranch on the Leota Bottoms, next to the Ute Indian Reservation in northeast Utah. I’ve been a hunter all my life, and killed my share of huge bucks. I knew the river bottoms as well as anyone, and learned where the big bucks lived. This buck, which I named Crooked Horn, was not only the weirdest deer I’d ever seen, but, as I’d soon learn, the smartest.

As soon as I saw him, I thought about the big buck contests that scored deer by the widest antler spread. A lot of sporting goods stores in Utah gave away expensive prizes for the biggest buck. A 40-inch outside spread was usually required to be considered in the contests. I knew Crooked Horn would be way up in the running, and probably the first-place winner. I could picture myself winning one of the four-wheeldrive vehicles that were top prizes, or at least a new Winchester rifle.

I spent all the time I could between ranch chores studying Crooked Horn’s habits and the places he frequented. I noted that he shied away from heavy timber, squaw bush and other places that impeded his travel. His wide antlers simply couldn’t fit through those tight spots. He bedded down in patches of sunflowers, young willows or other areas that had pliable plants but still offered concealment.

The closer deer season approached, the bigger Crooked Horn looked. His antlers seemed even wider when he scraped off the velvet.

I watched for him all day and dreamed of him all night. I was so excited and confident I’d get him that I signed up in big-buck contests from Vernal, Utah, to Las Vegas, Nevada.

A group of us, all friends, had hunted together for years. Each season the boys would gather before the opener and tell tall tales at the ranch house. This year, I was nervous as an alley cat, and couldn’t seem to get into the merriment and festive mood. I wanted to take Crooked Horn very badly and didn’t tell the boys about him. Somehow, I had to get away from the group so that I could hunt alone. There were some crack shots in our party; each of the men had plenty of big-buck racks nailed to his barn. Any of them could easily enough bust Crooked Horn before I’d have a chance.

I couldn’t sleep a wink the night before the opener. I tossed and turned and listened to the horses as they snorted and whinnied in the corral. The broncs knew what was coming up in the morning. We’d been working them hard, riding back and forth through the thickets along the river.

Long before first light, we gathered and planned our hunt. I think some of the boys grew suspicious of me, because I never made any suggestions or volunteered any information about our strategies. That was unusual, because I was more or less the leader of the group.

To hunt the river bottoms, the most successful method is to make drives on horseback. Because I was most familiar with the area, the men depended on me to plan the drives. I was pretty sure I knew where Crooked Horn was, so we hunted in another area. That old buck was going to be my trophy.

Hunting was fair that day. Several of the boys killed nice bucks. I hadn’t planned on it, but I had a good chance at a big buck and passed it up. The deer would have been an easy shot, but Crooked Horn was foremost in my mind. The boys knew for sure then that something was fishy. It wasn’t like me to let a big buck go by. Some of them guessed I was waiting for a special deer to show.

“Why didn’t you kill that big five point?” one of them asked as they gathered around. “Lew, you ain’t been actin’ right. You’ve got something up your sleeve.”

“Alright, fellers,” I said. “Guess I’ll tell you, although I’ll admit I wasn’t going to. There’s an unbelievable buck in the bottoms. He’s the biggest I’ve ever seen in my life, and I kind of wanted a crack at him alone. His rack is freak, and I’m sure it’ll go almost four foot wide, outside spread.”

“Holy mackerel,” someone said. “That buck will win a Jeep in one of the Salt Lake City big-buck contests.”

“I’m sure of it,” I admitted, “so let’s go get him. I know where he is.”

I felt a little better after the confession. It had been tough holding my secret in, especially because we were all pals.

We figured a plan for morning. Crooked Horn had been feeding in a meadow, so I planned to cut his tracks and find out for sure where he was. It would be easy to locate him, because he had tracks unlike any other I’d ever seen. Because he couldn’t get into the softer ground of the thickets on account of his wide antlers, he spent most of his time on the sand along the river. The sand wore his hooves in such a way there was no missing them. They didn’t wear and break off like normal hooves, but were longer and flat-sided.

Sure enough, the buck’s tracks were where I expected them the next morning, and they were fresh.

Our party spread out and worked through the brush. I cheated a little and stayed on the outside because I knew Crooked Horn wouldn’t go far into the brush — not with those handicaps on his head.

A couple of little two-points jumped but we let them go. Crooked Horn’s tracks led us to the river. The ornery cuss had crossed it, but we couldn’t follow him because the water was too deep for our horses. We rode back to our pickup trucks and loaded the horses, then drove to the little Indian settlement of Ouray where we could cross the river at the bridge. Then we cut back to where Crooked Horn should have climbed out of the water.

The buck hadn’t come up onto the shore at all. He’d just waded along the river and walked out onto a small island that was thick with trees and bordered by a grove of young willows. I checked and double checked, and was positive he was still on the island, unless he had swum off into deep water, but I doubted it. I was excited, more excited than I’d been on my very first hunt years ago. It looked as though we had the big buck cornered.

Right off the bat I knew Crooked Horn had to be in those young willows. We tied the horses on the mainland and left Colin, who was one of the best riflemen around, to watch a game trail that the buck might use if we jumped him. The rest of us went back to the upper end of the island, and made the drive afoot.

I’ve got to hand it to that buck—he stayed tight until we were almost on top of him. And when he made his break, he was fast and smooth. Crooked Horn tore down the trail, traveling at a full head of steam, and headed straight for Colin. Colin couldn’t shoot because we were in the line of fire behind the buck, so he figured he could jump on his horse and outrun the deer. Besides, he had to get off that trail pronto, because the buck was bearing down on him, showing no fear whatsoever. Colin jumped into the brush to where he had hidden his horse and tried to mount him.

Maybe the horse saw the wildly racing deer, or maybe he sensed Colin’s excitement. Anyway, he shied away, and Colin couldn’t get into the stirrups and swing up fast enough. By the time he got up all he could see was Crooked Horn as he crashed into the timber with his head turned sideways and the freak horn laying back alongside the buck’s ribs. Colin and his horse gave the deer a good chase, but never saw him again.

We gathered our horses and rode over to meet Colin. He was sick! The biggest buck he had ever seen could have been his if he’d stayed along the trail and shot instead of going for his horse. Crooked Horn had whisked by him only about eight feet away.

”What a buck,” Colin said as if he were in a daze. “What a buck. You were right, Lew. That’s the biggest buck in Utah.”

For the rest of the season we searched for the big buck and his tracks, but we couldn’t find him. He was lying low. The season closed without a trace of him. I worried that he might have been killed by poachers or other hunters, but I saw him soon after the season was over. I was mighty glad he was still alive.

The following year he gave us the slip after Vaughn chased him around the sunflower patch.

In 1961, the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife came into the area and started buying up land along the river to establish the Ouray National Wildlife Refuge. The government closed the grounds to hunting. We had only a 50-50 chance of finding Crooked Horn, because much of the river-bottom area where he lived was off limits.

I had been seeing the buck in the same patch of brush. His freakish horn looked even longer than before. When the season opened, the boys and I searched for the deer, but we couldn’t find his sign in the area that was still open to hunting. The sunflower patch was in the open hunting zone, but it had rained hard the night before the opener, obliterating the tracks. We decided to hunt elsewhere, and left Crooked Horn in peace.

Ralph Chew, an old-timer who hadn’t been hunting with us before, had heard all the stories about Crooked Horn. By now the tales were getting to be awful big stories. He decided to try for the phantom buck.

Ralph strapped his sleeping bag on his back along with some grub and proceeded to look for Crooked Horn’s tracks. He finally found them in the sunflower patch and even got a glimpse of the deer.

Seeing the tracks was enough for Ralph. The hunter took to the trail like a bloodhound, going slow and easy, stalking, stopping to listen, then moving on. When night came, Ralph rolled out his sleeping bag alongside the fresh tracks. By first light, he took to the tracks again. Shortly after following the tracks in the gray time before dawn, Ralph discovered that Crooked Horn had bedded down only 100 yards from where he had slept. The old-timer was elated because he was hot on the trail, but that elation turned to consternation when Ralph saw that the wise old buck had left his bed and went to Ralph’s bed. Crooked Horn was following him!

Ralph started backtracking, but so did Crooked Horn. No matter how hard he tried, Ralph couldn’t spot the buck.

That night, Ralph came into my ranch. He tossed his sweaty hat on the couch and plopped into a rocker.

“That’s the wisest old buck I’ve ever seen,” he confessed. “Any deer that smart deserves to live forever. I’m giving him up, Lew.”

Before Ralph went out the door, he turned and grinned, “In a way, I’d sure love to set fire to that danged dried-up sunflower patch,” he said. “Then that old buck wouldn’t have a sanctuary to hide in. But then again, I’m glad those sunflowers are there.”

Read Next: Why Do I Hunt? The Answer to Hunting’s Toughest Question

The boys and I hunted Crooked Horn through that season after Ralph gave up, but we never saw the buck. As always, his tracks were there to taunt us as we searched in vain.

Before another hunting season came along, the federal government had bought almost all the ground along the river for the refuge, including the Leota Bottoms where the sunflower patch was. The area was closed to hunting, and Crooked Horn wouldn’t have to worry about us anymore.

The last time I saw the great buck was in late November 1964. He had a harem of does, and I hoped that he would pass on all his wonderful qualities to his fawns.

As I watched him, I couldn’t help but rejoice that he had stayed alive. I took off my hat and tipped it to him, and then rode away on the dusty trail. I pulled my mackinaw up around my neck and put the spurs to my horse. I turned for one last look, but Crooked Horn was gone. Chuckling a bit to myself, I knew he’d be headed for the old sunflower patch.

Read the full article here