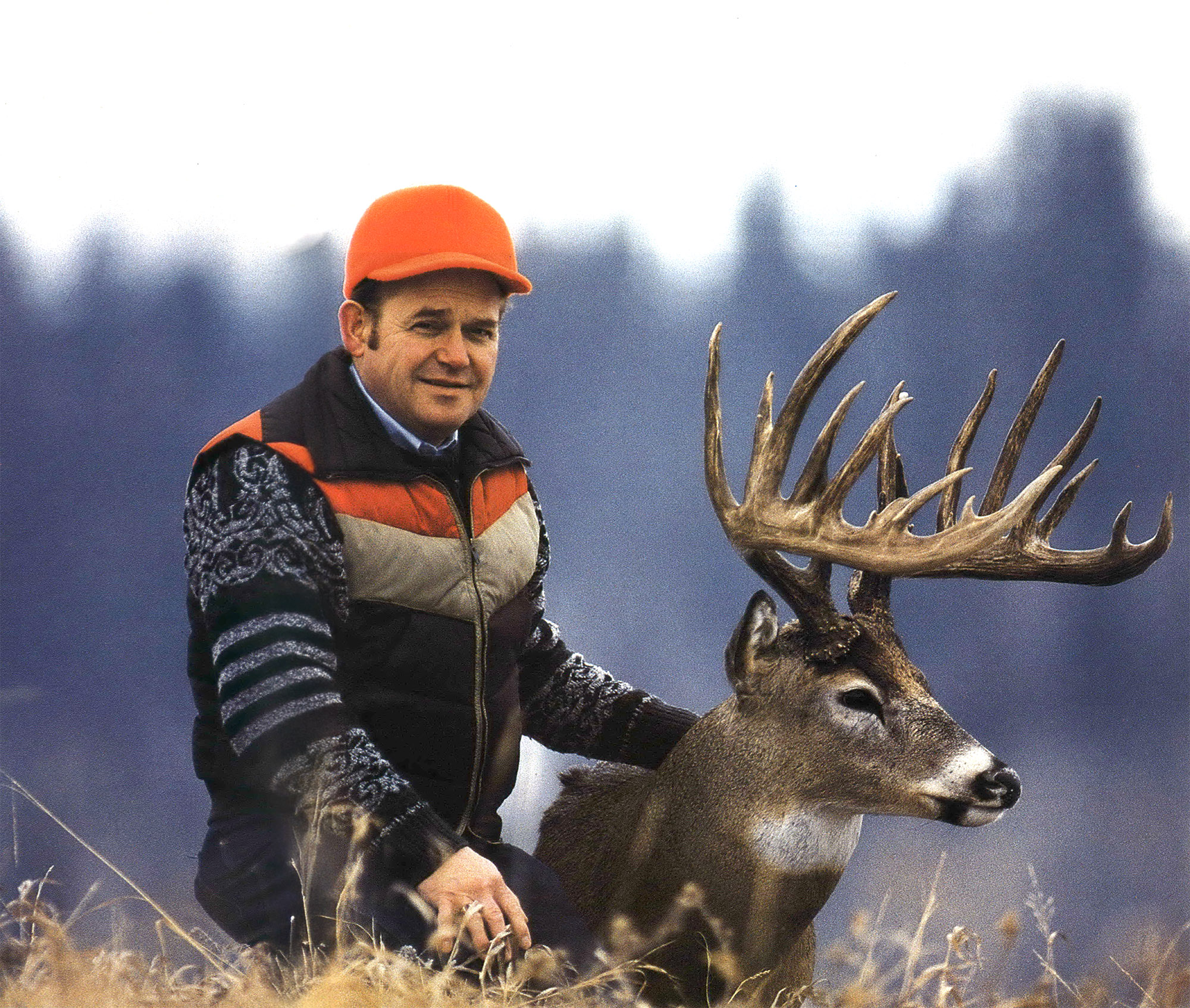

The Hunt for the Ed Koberstein Buck, a World-Record Contender That Lost After a Scoring Mixup

This story, “World-Record Whitetail?” appeared in the May 1992 issue of Outdoor Life. The Koberstein buck grossed 235 5/8 inches, netted 207 2/8 and was expected to replace the Jordan Buck as the new world-record typical whitetail. But a panel of scorers ruled the G6 points abnormal and dropped its net typical score to 188 3/8.

“Before the dust settled it was determined that Mr. Koberstein’s buck was incorrectly measured and should have been scored as a non-typical,” the Boone and Crockett Club’s then-director of big-game records, Jack Reneau, wrote in 1994. “Sadly, Mr. Koberstein’s trophy will never get the recognition it so justly deserves as he has decided that he would not have it rescored [as a non-typical].”

As a result, the Koberstein buck is ranked today as the 11th biggest typical ever killed in Alberta. And yes, this story was written by that Jim Shockey.

The year was 1914. James Jordan of Danbury, Wisconsin, raised his .25-20 Winchester, sighted along the rifle’s open sights and gently squeezed the trigger. In doing so, Jordan unknowingly ensured that his name would forever be a part of history. On that fateful day nearly 80 years ago, James Jordan killed the largest typical-racked whitetail that had ever been taken. The buck he was aiming at turned out to be a world record that was to stand unassailable year after year, season after season. The Jordan buck: 206 1/8 Boone and Crockett Club points.

The year was 1991. Ed Koberstein of Lacombe, Alberta, felt his pulse quicken. There was something running through the woods behind him. Slowly he turned his head a full 180° and immediately picked up the telltale brown and flash of antlers 40 yards away through the poplars and spruce. Buck!

His heart beat still faster, but Koberstein held back his strongest impulse to swing around and snap a shot at the now-standing deer. Though the animal was largely obscured, Koberstein’s instincts dictated that he hold still. The wind was from the deer to the hunter, but the buck knew something was wrong. He lowered his head to see better, peering through the bush at the hunter. Five seconds, and then 10, the standoff continued. One minute passed, and still the hunter held. The deer began to stamp one of his front hoofs, try ing to goad the hunter to movement, but the hunter remained motionless. The buck snorted. The hunter didn’t budge.

Finally, well into the second minute, the buck lifted his head and looked to the side. It was the opportunity that Koberstein had been waiting for, and so even as the buck turned, the hunter shifted to bring his rifle to bear.

He pointed the rifle toward the spot where he felt the deer’s body should be, but to no avail: He couldn’t find the buck in the scope. For a few tense seconds Koberstein searched through the lenses for a gap in the trees, but he was unable to locate the buck. Still he didn’t panic. Instead he lowered the rifle to look over the scope and confirm the buck’s position. Once again he raised the gun, and this time he saw the brown hairs behind the buck’s shoulder. Holding his breath, his heart pounding, Ed Koberstein gently squeezed the trigger. …

Like many of us, Koberstein grew up with hunting. Born in 1945, he remembers that there was seldom a year when his family went without venison. His father was an avid outdoorsman with a strong sense of fair chase and sportsman ship. His father’s passion ·was a love of nature — a love passed on to all six of his children. Ed was the youngest, and he followed his two brothers, three sisters and father into the field.

Related: Solving the 65-Year Mystery of the Jordan Buck, the Biggest Whitetail Ever Killed in America

“I started to hunt as soon as I was legally able to carry a gun,” Koberstein said with a smile recently, thinking back on his childhood. “But maybe I snuck out earlier.”

The Kobersteins hunted and fished around the family farm near Barrhead, Alberta, Canada, and usually they man aged to bring home something for the table. Whether it was ducks or grouse in the fall or fish in the summer, the family always had a well-stocked larder.

As is so often the case, Ed Koberstein left the family farm at a young age to seek his fortunes in the city. Hunting, a part of his childhood, was destined for the better part of 20 years to be just that: a part of his childhood. In fact, it was not until 1978 that Koberstein’s passion for hunting was rekindled and he was once again tempted to take to the field.

“My brother-in-law talked me into taking a trip north for moose,” Koberstein recalled. “I didn’t shoot it, but we got one moose. And I have been hunting every year since.”

That first year back to hunting, Koberstein used his dad’s old .303 rifle, but he bought a new Remington Model 700 in .270 Winchester when he re turned from the trip. He mounted a Leupold Vari-XII 3X-to-9X variable scope on the rifle and had a friend handload several boxes of ammunition for him.

Interestingly, though Koberstein hunted for years, it was not until seven years ago that he actually shot his first deer. He’d chosen not to shoot in the past because he’d only wanted a good buck.

His first buck was “a bit of a freak,” with four points on one side and a “mess on the other side.” He took the buck with one shot at 275 yards.

In 1988, Koberstein took the second big-game animal of his hunting career. It was a moose.

The 1991 season rolled around as all the other seasons before had. Without knowledge of what the season would bring, Koberstein began the year with a trip that was, in his own words, “thoroughly enjoyable.” He and three hunting partners headed west toward the mountains.

“We were primarily hunting moose and elk,” Koberstein said, “but I had a mule deer tag and a whitetail tag.”

It was the last week in October, and it took the party five hours to travel to their hunting spot during a blizzard. When they arrived, they discovered that the snow was too deep to allow hunting on foot, and instead they were forced to use the six days working the logging and oil field roads-something the party does not normally do.

“We saw 23 moose, 14 elk and seven deer,” Koberstein said. “And not a single one had antlers.”

The temperature hovered around 25° below zero, making for cold tenting.

“The one with the poorest sleeping bag stoked the fire,” Koberstein laughed.

While helping to break camp on the last day, Koberstein had the tent’s ridge pole, fully 30 feet long, come crashing down on him, fracturing his shoulder blade. It was hardly a trip that most of us would describe as “thoroughly enjoyable,” but for Koberstein it was. He was outdoors.

It looked like the injury might keep the hunter from his annual four-day trip to the eastern regions of Alberta, but as it turned out, it was not the injury that kept him from making the hunt. As much as he was looking forward to the trip, Koberstein learned that he would be unable to attend due to a commitment at his office, where he is the secretary treasurer of the local rural municipality.

“I thought my hunting was over for the year,” Koberstein recalled. And perhaps it would have been if another of his brothers-in-law had not called and invited him out for a deer hunt on the week end of November 23.

Koberstein did not know the other members of the hunting party, but he thought that it might be his last chance to get out, so decided to go.

He and his new partners gave it their best attempt, hunted hard and saw several deer, but nothing that they wanted to shoot. The Saturday was, for the most part, forgettable — except for one particular drive. Koberstein was posting on that drive, and he had chosen a log to sit on while he waited for the push to begin. Within minutes he heard a deer running behind him, and by twisting around was just able to make out the animal through the under-growth. The deer stopped and looked at the hunter. Koberstein was able to see that the animal didn’t sport antlers, and so he let it pass. The drive ended without any further action.

“I started walking, but when I got within 40 feet I saw the deer and started running.”

Though the hunt was uneventful, where he had sat during that drive stuck in Koberstein’s memory. There was something about that spot that he liked — something about the log, or maybe something about the way he’d felt when the doe ran by. When he had been sitting there he had had a good view up and down an old trail. Whatever it was about that spot, Koberstein remembered it.

In the area of Alberta where the group was hunting, the season is closed on Sundays, so Koberstein had no choice but to leave things for another day. He traveled out to his brother-in-law’s to watch the Grey Cup football game, Canada’s version of the Super Bowl, and naturally the conversation turned to hunting.

“My brother-in-law told me that he had seen a big buck that morning,” Koberstein remembered. “He saw the buck fairly close to where I had been hunting the day before.”

Once again Koberstein decided to give it go, and so made plans to meet his new hunting partners around 9 a.m. the following morning. Koberstein had an idea. He wanted to head out earlier and sit on the log he’d found the day before.

And so on that fateful morning of November 25, 1991, Ed Koberstein quietly crawled out of bed, dressed in his hunting overalls, made a thermos of coffee, donned his felt pac hunting boots and drove the 20 minutes from home to his chosen hunting spot. He turned into the field, parked his vehicle, pulled out his rifle and a cushion for sitting on, then headed into the woods and to his date with destiny.

It was light by this time, and Koberstein had only traveled 300 or so yards when he heard a deer snorting at him. He crouched low and tried to see the animal, but the distance through the thick undergrowth was too great. After five minutes the deer left. Koberstein waited awhile longer in case another deer was following, but when none showed, he continued on. It was nearly 8 a.m. when Koberstein found his log and cleared the snow from it. He sat with his back to the south, choosing to face the direction where he had the best line of sight.

For 10 minutes Koberstein sat. During those 10 minutes, Ed Koberstein could have been any one of us. He was an average guy, like any of the tens of millions of hunters who take to the field come hunting season-like any of the hundreds of millions who have taken to the field since James Jordan lifted his old .25-20 and squeezed the trigger in 1914. Little did he know it, but those 10 minutes were the last minutes that Ed Koberstein would ever spend as one of the hundreds of millions. When Ed Koberstein squeezed the trigger, his .270, he became one in the hundreds of millions.

“I didn’t take much time to decide to shoot,” Koberstein recalled. “Instinct took over. I was chambering a second round when I realized the buck was gone.”

Koberstein was stunned. Self doubt began to set in.

“I thought maybe I’d hit a twig. I just sat there trying to figure out what in the devil had gone wrong.”

He sat for nearly a half-minute before finding the will to stand and walk to where the buck had been. It was then that heard movement.

“Later, I stepped it off at 43 yards,” Koberstein said. “I started walking, but when I got within 40 feet I saw the deer and started running.”

Koberstein’s excitement is infectious as he recounts his initial feelings. “I could not believe my eyes when I first saw his antlers.”

Still Koberstein was unaware of just how big his buck was.

“I knew it was my number-one deer,” he said. “That’s what counts.”

Koberstein’s first shot had hit the buck in the spine, dropping him in his tracks. The hunter raised his rifle one more time to quickly end the great buck’s life.

Then, as was fitting, Koberstein took a few moments to admire his trophy.

He paid his last respects before stepping into the record books forever…

Read Next: The Mystery of the Ahrens Buck, a World-Record Whitetail That Vanished

Though Ed Koberstein may never again be, as he describes himself, “just anverage hunter,” it is comforting to know that in one very important way he will never change. You see, his father in stilled deeply within his son a code of ethics that will forever ensure that Ed Koberstein remains, above all else, a sportsman.

Editor’s note, from 1992: The Koberstein buck sported 20 scorable points and had 28-inch-plus main beams. After the mandatory 60-day drying period, the antlers grossed a total of 235 5/8 Boone and Crockett Club points. With deductions, the final net score was a whopping 207 2/8 — a full 1 1/8 points greater than James Jordan’s current world-record typical whitetail. (For all of the measurements, see the copy of the official score sheet above.) It should be noted that the Koberstein buck will not be certified as the new world record until it is officially panel scored by the Boone and Crockett Club in 1995. —The Editors.

Read the full article here