Pat McManus Once Sabotaged the BASS Masters Classic

You make a lot of enemies in my business. Word on the street was that some guys in Montana had put out a contract on me because of the last job I did there. Sure, the contract was for only $3.98, but times are tough and people will take any work they can get. While I was riding the bus to work, a hit man tried to take me out by tying a plastic bag over my head. He apologized for not being able to afford bullets. I told him to forget it and gave him a buck for making an effort to stay off welfare.

When I got to my crummy office that crummy Monday morning, my crummy secretary was soaking the mail in a bucket of water. A lot of guys have dishwater blonde secretaries. Maizy is dishwater all over.

“Anything of interest, Maizy?” I asked.

“Naw, just the usual ticking package and lump envelopes marked ‘Handle with Care.’”

I wandered into my crummy private office and flopped down at my crummy desk. I felt like a cigarette. It was an odd sensation, and I wondered if maybe I should consult a nerve specialist. Then the phone rang.

“McManus here,” I answered gruffly, all business.

“Mr. McManus,” drawled a voice soft and Southern as cheese on hot grits, “this is Renee Wheatley in Montgomery, Alabama. I work for Ray Scott.”

Ray Scott! The man was a fishing legend! Some years ago he had invented the bass in his basement during nights after work as an insurance agent. He became so obsessed with the fish that he started to devote all his time to it. Rapidly, his basement began to fill up with bass. Then his wife told him to get his bass out of the house and start making some money. So Scott did. He started promoting professional bass fishing tournaments and organized the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society or BASS. Both were a big hit with anglers around the country, and it wasn’t long before Scott’s basement began filling up with money.

Renee’s melliferous voice interrupted my recollecting. “Mr. Scott has requested your presence at the 11th Annual BASS Masters Classic in Montgomery.”

“That’s a tough assignment,” I said. “I’d be going up against the top bass fishermen in the country.”

“Mr. Scott believes you can handle it. He knows about your, er, uh, talent.”

“But why?”

I can’t tell you that. Mr. Scott just wants you to come down here and do, uh, your thing at the Classic. Oh, by the way, he said he thought it would be best if you traveled incognito.”

“Forget that, baby,” I said. “I’m gonna fly.”

Odd, I thought after hanging up. Ray Scott had a reputation of being a bright, honest, rich human being. Now he was pulling me in to do a job on the contestants in his own BASS Masters Classic. I had been in on some weird capers in my time, but this was the weirdest.

Just to be on the safe side, I decided to pack a rod. Then I decided it might be even safer to pack three rods — two casting and one spinning.

I told Maizy not to expect me back for at least a week.

“I see you’re goin’ to Alabama,” she said.

“What makes you think so?”

“The banjo on your knee. It’s a dead giveaway.”

I was getting careless. In my business, little slip-ups like that can cost a man his life. The six-hour flight to Montgomery gave me plenty of time to bone up on the 11th Annual BASS Masters Classic and try to figure out what Ray Scott was up to.

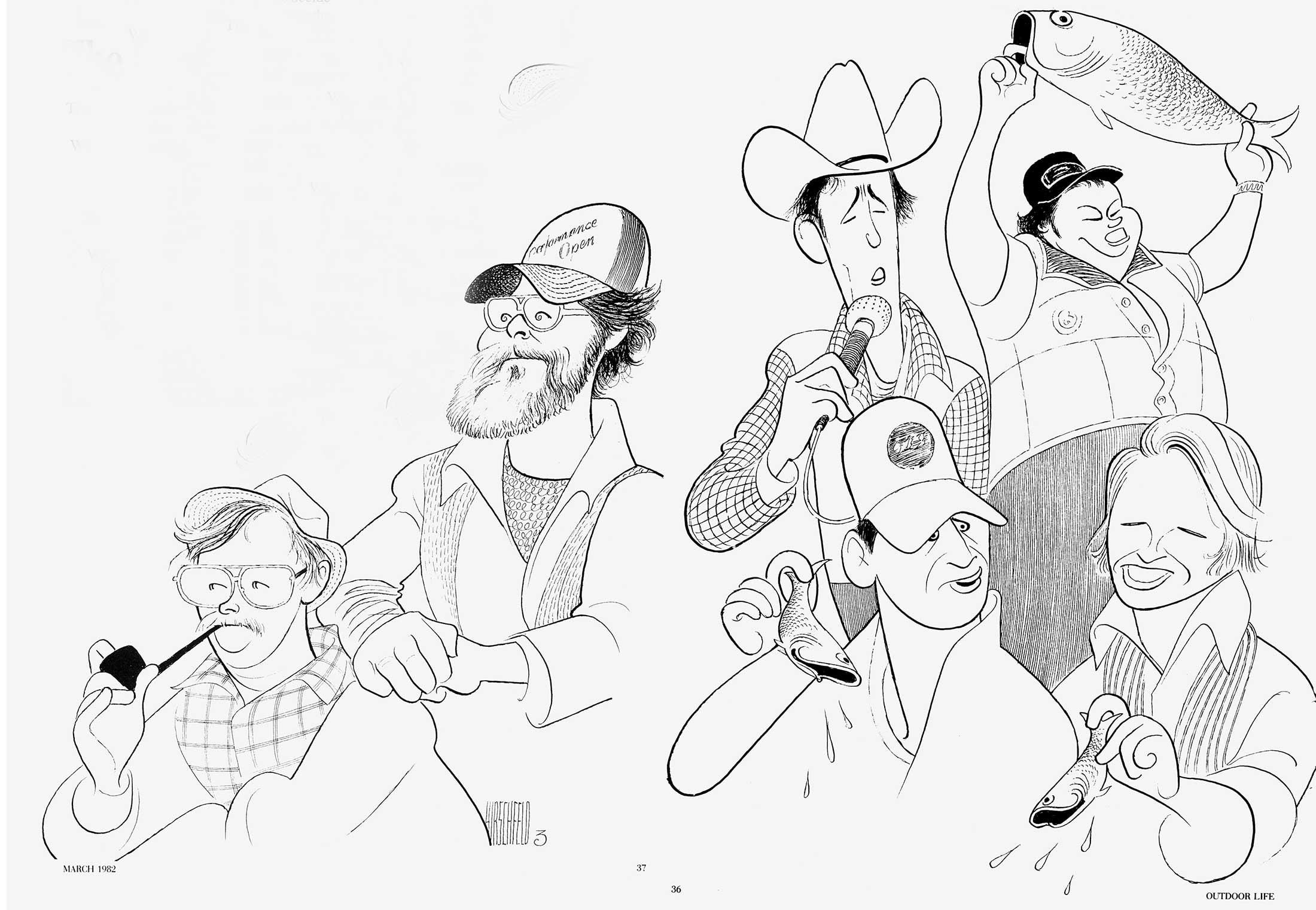

One thing was clear: I’d be going up against 42 of the best bass fishermen in the world, guys like Roland Martin, Bo Dowden, Jimmy Houston and Bobby Murray. Most of them made their living as bass pros, fishing anywhere from 150 to 300 days a year. It was said that every one of them went over a piece of water like a human sieve.

I had been told that some of the contestants even thought like bass. That seemed unlikely. I know quite a few people who think like bass and they don’t even fish.

It was much more likely the bass pros would be to fishing what Einstein was to physics. They would have reduced catching bass to a mathematical equation. They would extract bass from the water with the regularity of a metronome and the precision of a computer. They would be tough. I began to worry that the old magic might not work against this kind of competition.

About the old magic. Many years ago I discovered that I have a psychic power over fish. Merely by showing up at a lake or stream, I could make the fish stop biting. If I rigged up and made a few casts, the fish would fall into a catatonic state and sink to the bottom, where they would remain as immobile as lox on a bagel until I took leave of the place. Scarcely would my departing epithets have ceased echoing among the distant hills, however, than the fish would arouse from their stupor and chum the water into a maelstrom in their frenzy of feeding.

Soon my friends refused to fish with me. As my reputation for shutting off fishing began to spread, local anglers began pleading to have my intended fishing destinations included in televised fishing reports so they could go where I wasn’t. News of my reservations at fishing resorts brought more cancellations than an epidemic of botulism. It wasn’t long before angling groups around the nation were trying to get me banned from their states as a dangerous substance. I felt like an outcast.

Then a peculiar thing happened. Other fishermen began looking upon me as a challenge. They would make bets that they could catch fish even if I was in the vicinity. Guides would stake their reputations on the promise that fishing parties would catch fish regardless of my being along. I beat them all. But I must say it is a pitiful sight to see a grizzled old fishing guide, tears streaming down his cheeks, pleading. ‘”Cast into that hole one more time. I know there’s fish in there!”

Finally I went into the business of shutting off fishing on a full-time basis. I called my firm ”The Empty Creel” and handed out business cards with the motto. ”This rod for hire.”

But why was Ray Scott bringing me in to shut down the 11th Annual BASS Masters Classic?

I knew that Montgomery was Scott’s hometown. It seemed unlikely he would want to disgrace himself in front of the home folks by putting on a BASS Classic in which no bass were caught.

Ordering another Scotch from the flight attendant. I decided to check the rules for the tournament.

“Holy cow!” I shouted and downed the Scotch in a single gulp.

“What is it?” the passenger in the seat beside me yelped. “One of the engines on fire?”

“Nothing so mundane as that,” l replied, prying the man’s fingers loose from my leg. “I just discovered what Ray Scott is up to!”

Having given the tournament rules the once-over, I had no trouble imagining the following scenario: Scott and his head henchmen, Harold Sharp and Bob Cobb, are sitting around a table working up the regulations for the tournament.

“As you know, I don’t want this BASS Classic to be too easy for the guys.” Scott says, chuckling evilly.

That was probably how it had happened, all right. Ray Scott hoped to get the 1981 BASS Classic into the Guinness Book of World Records as the toughest ever!

The jet banked over Montgomery and I peered down at the beautiful Alabama countryside cloaked in forests and sparkling with lakes, creeks, and rivers, wondering if the bass down there had yet detected my presence. I was consumed by the wonderful, glowing feeling that comes from the sense of my own great psychic power. The other passengers were staring at me strangely. It took a moment for me to realize I had been going, “Henh-henh, henh-henh!”

The Classic consisted of two practice days and then three days of the real thing. I didn’t go out the first practice day but stayed at the hotel, just to see if my presence in the general vicinity would affect the bass. That afternoon I wandered down to the Montgomery Civic Center, where the day’s catch of bass was to be weighed. I had no trouble keeping my enthusiasm in check. After all, what kind of drama can you expect from weighing a bunch of bass?

I had underestimated Ray Scott.

Right there in Montgomery, Alabama, he produced the world’s first bass-weighing spectacular! Thousands of spectators crammed the bleachers. Television crews manned their cameras. A hundred reporters and photographers jostled for position. Strobe lights flashed. A huge overhead screen provided the audience with a televised close-up of the action. And the fish scale! Where I had expected one of the little spring-loaded jobs, there was this magnificent electronic device that flashed out the pounds and ounces and fractions of ounces for the entire audience to see at the precise, existential, electrifying moment that each bass was weighed. One could not help but be humble in the presence of it all.

Ray Scott himself, nattily attired in a brilliant green sport coat and white cowboy hat, served as master of ceremonies. A consummate showman, he worked the crowd up to such a feverish pitch you would have thought he was preparing them for gladiators to bound into the arena and have at one another with sword and ax. Instead, the crowd awaited only a few dozen weary bass fishermen and their catch, if any. If I hadn’t been so caught up in the excitement, I would have succumbed to astonishment.

One of the more interesting wrinkles of the show was that the bass pros and their press partners remained in the boats while being towed to and from the Civic Center. I wasn’t sure whether this was common fishing practice in Alabama or if Ray Scott had just invented it for the Classic. In any case, the sight of fishermen being towed through town in their boats gave the proceedings just the right touch of levity, or so I judged from the number of pedestrians collapsed on the sidewalk in fits of laughter. What was astounding, however, was the thunderous applause given to each boat and its occupants as they were towed grandly into the arena.

I was nervous. The magic didn’t seem to be working against these pros. Then Ray Scott called Jimmie Houston up to the microphone and asked him how many fish he had caught and released.

“Only seventy-two,” Houston said.

I shuddered. Only seventy-two? Then I noticed that Houston was squinting. He’s from Oklahoma. It’s a well-known fact that Oklahomans can’t tell a lie without their eyes twinkling. Jimmie was squinting to cover up the twinkle! He was lying!

I eased up behind Bobby Murray, who was talking to a grim Roland Martin. “There ain’t no damn fish out there,” Bobby whispered. Roland nodded in agreement.

Sure! In spite of all the razzle-dazzle put on by Scott, the simple fact was that pitifully few fish over 14 inches had been caught and some of those had stretch marks. Boat after boat had come in without a single bass. True, only the reporters were allowed to bring in bass on the practice days, but it was evident from the expressions on the faces of the pros that my old magic was working. And I hadn’t even drawn a rod yet.

The next day I went out with bass pro Harold Allen from Batesville, Mississippi. Harold seemed like a pleasant enough fellow at first, and we chatted amiably as we were towed in our boat down to the launch site. We were in the first flight of 15 boats to line up across Lake Alabama to await the starting signal and the race down the lake to find the best bass water. I took the opportunity to study ole Harold. Even much later, after I analyzed the situation, I concluded

that there was nothing in his easy-going manner that in the least suggested homicidal tendencies. Then a peculiar thing happened.

Ray Scott stood up in a boat and recited a prayer over a portable amplifier. I can’t recall the words of the prayer exactly but it had something to do with everybody returning alive and unmaimed. Well, that certainly caught my attention. I turned to ask Harold whether the prayer was just a formality and discovered it wasn’t. He was crouched over the steering wheel, his eyes all gleaming and terrible and his bearded face contorted in a monstrous grin.

“W-wait,” started to say. “I want out!”

But it was too late. Harold pulled the trigger on the Merc 150 and shot us 20 miles down the lake. I opened my mouth to tell him to slow down but my cheeks filled with air and began beating against my ears like toy balloons in a gale. Occasionally Harold would flatten our trajectory enough to get us under bridges, but then he would open her up again. The depthfinder was recording low-flying ducks. Smaller birds zipped past like tracers. And then, suddenly, just as I was reaching over to get a grip on Harold’s windpipe, we sank back into the water.

“That fast enough for you?” Harold asked, having returned to his old amiable self.

“Phamf glimp,” I replied calmly, forcing a smile. I had to force the smile because one of my lips was still hooked over an ear.

Harold was as fine a fisherman as I’ve ever seen. He fished hard all day, taking time out only long enough to disentangle me from my backlashes or tie one of his own lures onto my line.

“The Lord should love me for this,” he would mutter.

Harold Allen turned out to be one of the nicest human beings you could ever expect to meet, and I began to feel bad that I had shut off the fish for him, because I surely had. He got only three or four strikes all day and landed a single miniscule bass. Then, late in the afternoon, he did a strange thing.

With only an hour left of the last practice day, time with which he might have tried to find a ”honey hole,” he started driving the boat up a river. Giant beech trees lined the river on both sides, and the sun, low in the West, sent rays of orange light filtering through veils of Spanish moss and streaming across the water. Here and there we would catch a glimpse of a field of cotton in bloom, golden in the sunlight. I couldn’t figure out what Harold was up to, for the river seemed an unlikely place for bass. Finally, Harold stopped the motor and let the boat drift with the current. He sat there quietly, looking around, not even picking up one of his rods. I began to get nervous again. Then ole Harold spoke.

“Beautiful ain’t it?” he said.

Well, I’ll tell you. I was dumbfounded. Here was a professional bass fisherman with a $40,000 first prize at stake, and he used the last hour of the last practice day simply to enjoy the scenery. I had never seen anything so dumb. Clearly, Harold lacked the killer instinct. I decided not to waste any more of my power on him. After all, I had already saved some power by withdrawing it from a 21-year-old kid from Georgia, Stanley Mitchell, who obviously was just too young and inexperienced to be a real contender in the tournament. I knew Ray Scott wouldn’t want me wasting power on contenders who wouldn’t stand a chance anyway.

The rest of the tournament went about the way I had expected. There was much heated discussion among the bass pros about the inactivity of bass in the lake. Some thought it was because of a cold front that had moved through. Others claimed it must be because an upstream dam wasn’t releasing water into the lake. But Ray Scott managed to keep tempers under control by throwing cocktail parties every night, along with sumptuous feasts and floor shows.

One night he even went so far as to make all the bass fishermen and outdoor writers dress up in tuxedos and listen to violin music. He probably thought it was a good chance to instill a bit of culture into both of these groups, but it didn’t work. If you haven’t seen a bunch of bass fishermen and outdoor writers trussed up in tuxedos and still wearing their cowboy boots and cowboy hats, you have saved yourself from one ghastly spectacle. It looked like a bad collision between a symphony orchestra and a gang of cattle rustlers. The catastrophe was too much even for Ray Scott. Afterward he let the guys wear what they wanted and replaced the violins with belly dancers, country and western singers and rock bands. A man like Scott doesn’t get rich by pursuing hopeless causes.

I had only one close call. While quaffing at a cocktail party, I was recognized by Roland Martin, who hadn’t yet caught a single limit of bass. Roland knows of my reputation for shutting off fish. I could see the light dawning in his eyes and thought he was about to blow my cover. But Roland is a gentleman and humanitarian and allowed me to escape undetected. Afterward, though, he fished listlessly, with the attitude of a man who knows there is no hope.

I won’t even try to describe the grand finale Ray Scott staged for the weighing of bass on the last night of the Classic, except to say that a presidential inauguration or World Series seems pallid by comparison. And here I had thought I might go all the way through life without hearing a crowd burst into a deafening roar over a bass that blipped out on electronic scales at 3 pounds, 4 ounces. When I saw what appeared to be a six-pounder headed for the scales, I ran for the nearest exit, fearing that the ensuing tumult might bring down the roof of the Civic Center.

I packed and went home. Ray Scott should have been pleased by my performance, since most of the bass pros agreed they had never had a tougher time catching fish. On that score; the 11th Annual BASS Masters Classic would be a shoo-in for the Guinness Book of World Records.

Read Next: A Farewell to Pat McManus, One of Outdoor Life’s Most Beloved Writers

I had only one regret. The two top money winners were young Stanley Mitchell from Georgia, who came in first, and ole Harold Allen, who came in a close second. I thought the very least they could have done was divvy up their prize money with me.

But you know how it is with bass fishermen.

Read the full article here