Lessons Learned from a Lifetime of Elk Hunting Adventures

By the halfway point I was drenched in sweat and had drained half of my water. But with only an hour until daylight and over 1,000 feet yet to ascend, slowing down wasn’t an option.

I knew where I wanted to be based on experiences the season prior. That was the first time I’d bowhunted for elk in this mountain belt within Montana’s interior. I spotted a bull I on that trip during the initial moments of opening day that carried a rack every bit of 380-inches. The standard had been set.

I called in eleven branch bulls to inside 40 yards on that first hunt. Three were bigger than any bull I’d ever killed. But they were diminutive compared to the beast I laid eyes on opening morning. For seven days I hunted hard, never going to base camp except to sleep, only occasionally slipping into the bottom of wooded draws to replenish my water supply. I went home with a tag in my pocket, humbled by the big bull’s elusiveness.

Though I never shot an arrow on that first trip, I learned a lot. I made mistakes, got overly aggressive at times, moved too timidly at others. But over the course of the week I had located an area with fresh wallows and elk trails etched deep into the pine forest mountains. By the time I found them it was too late in the hunt to capitalize. But I was ready the following year, with another tag to burn.

A Lucky Bugle

The goal on this morning was to climb uphill and be in position, below the wallows, once the thermals stabilized. To pull it off I left camp at 2:30 a.m., hiked up a ridgeline a half-mile to the north of the wallow, then waited for the cooling, falling thermals to switch direction. Once the sun hit the east-facing mountainside, it didn’t take long for temperatures and air currents to rise. When I felt the uplifting breeze sooth my overheated body, it was time to move in.

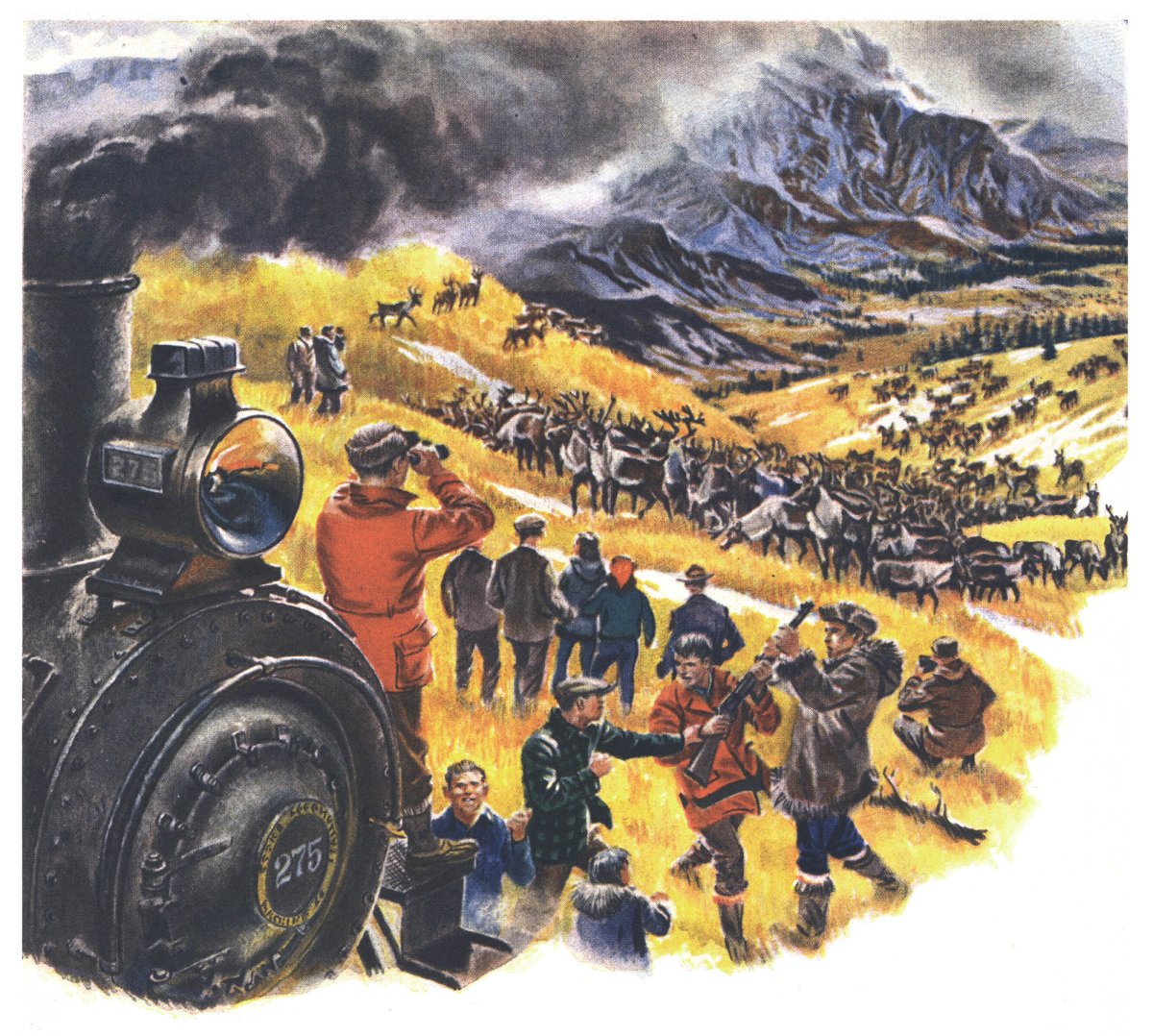

I made it only 30 yards when a herd of more than 50 cows appeared on the edge of an opening, a half-mile below. A lone bull fed near them, beneath some quaking aspens. I cow called. The bull lifted its head and bugled. I bugled back. The bull responded one more time, then tossed its heavy rack across its back and began prancing my direction. This shouldn’t have been happening. But there are no set rules when it comes to elk hunting and animal behavior, especially during the rut.

With only sparse, waist-high sage brush to hide in, I made the most of it. The bull covered 700 yards surprisingly fast. When it held up in some timber, I bugled. The bull fired back, then tried circling downwind of where I crouched. Figuring the gig would soon be up — the bull would surely catch a whiff of the stench from my sweating body — I tried a desperate bugle to try and convince him to come right at me, rather than circle in. It didn’t work. But when another bull bugled in the trees up and to my right, the target bull couldn’t resist.

The regal 6×6 stretched its neck, pumped the air with its black, wet nose, then turned 90 degrees and headed uphill, right in front of me. When the bull got to 40 yards, I reached full draw and let out a cow call. The bull stopped, perfectly broadside. The shot was anti-climatic. Hit through the lower lobes of both lungs and taking out the upper heart, the broadhead did impressive damage. The bull went 70 yards and piled-up. Had it not been for the other bull bugling at just the right time, I wouldn’t have killed that bull. And while it wasn’t the monster I’d seen a year prior, he was a dandy nonetheless.

Wallow Trickery

The goal of that hunt was to move near the wallow and intercept bulls as they moved toward it following a night of feeding, or chasing cows. The year prior, all the fresh mud I’d seen surrounding the wallow was on the uphill side. Those splashes of water and mud around the wallow indicated bulls were moving uphill early in the morning. Virtually no mud splashes existed below the wallow, meaning once cows headed out to feed, the bulls followed them rather than stopping to wallow.

I’ve learned a lot by studying elk wallows over the years. Splash marks and tracks in wet ground indicate which direction bulls are moving when leaving a wallow, even what time of day.

If you really want an education, set a trail camera on a wallow. If you can’t set up a camera during summer scouting missions, do it on day one of the hunt and check it every other day (assuming this is legal in the area you are hunting). Earlier this month I caught four different bulls and four bears in one wallow in one day. Last year I caught seven bulls in one wallow in a single day.

On another hunt in the Rocky Mountains I found what I thought was a fresh wallow. The sweet stench of rutting bull hung in the air. There was no wind. I didn’t want to risk spooking a bull by closing in too near to inspect the wallow. So I moved and called around that wallow for two hours one morning. The rubs on the trails leading to the wallow also looked fresh. Then I looked closely at one.

Sap hung on the stripped tree. It glistened in the morning sun, so much so, it looked wet. When I touched it, I discovered otherwise. The sap was dry. Hard as a rock. The bark, though white and seemingly wet from the thrashed cambium layer, was also dry. Void of moisture, the strips of bark curled up on the edges. The next rub revealed the same details, as did multiple others. The rubs were several days old.

Then I headed to the wallow. I stirred it with a stick. Sediment stayed suspended for several minutes. There was no current flow. I’d been fooled. The area looked and smelled like elk had recently been there. Later that afternoon I found a herd of elk more than three miles from the wallow. Don’t just look at sign, study it.

Running and Gunning

When on a bowhunt for Roosevelt elk late one September, the conditions were perfect. The night prior, the first rains of fall arrived. The next morning, temperatures were cool in the Coast Range. Bulls were bugling, even before I made a sound.

I’m a firm believer that waning photoperiodism triggers the rut, not cool temperatures. But cool temperatures encourage testosterone-induced bulls to move around in comfort, their large bodies cooling more quickly. When such conditions prevail, I love hunting aggressively. Covering ground and calling a lot are my go-to approaches.

On this day I set out as I had many other times under these conditions. Cow calls and bugle tube in-hand, water bottle full, ready to hike. In situations like this, I work the shadows and cover real estate. I don’t care if a bull sees or hears me walking, but if they smell me, the gig is up. I don’t use cover scent, because I’m sweating to the point that nothing can mask the smell. It’s hard for a hunter to comprehend how good a bull’s sense of smell is, and there’s no way to mask the smells coming from heavy breathing out of your mouth, from the sweat dripping off your head, or even your sweaty palms. I’ve killed plenty of bulls that have seen and heard me, but I’ve never got a shot at one that smelled me.

On this day I was into my second wind-check bottle by 10:00 a.m. If the wind shifts, back out and come in from another angle or return another day. If the wind holds in your favor, keep moving.

I found a big Roosy’ bull I really wanted, but no matter how seductive my calls, the bull wouldn’t leave its nine cows. When a little 6×6 came charging in, I figured the big bull would follow. It didn’t. Instead the herd bull gathered its harem and slowly headed into the Douglas fir forest. It wasn’t rushed, just irritated, so I kept after it. For three quarters of a mile I trailed the herd, laying eyes on the big bull multiple times. That little 6×6 came to my calls five more times. Every time it was inside 20 yards.

Later in the morning I got on another herd. A nice six point bull — though not near as big as the previous one — was with more than 30 cows, a lot for a Roosevelt bull to manage in their jungle-like habitat. The bull only occasionally bugled at my cow sounds and insubordinate bugles. The herd moved through the timber and into a tiny meadow to feed. Just when I thought I had a chance, the cows began lining out and heading toward the timber on the opposite side to bed down for the day.

My window was brief. I stuck tight to the shaded trees and ran right at the herd. They heard every step I took on the dry ground. Each snapping branch, every twig I stepped on. But they also heard the range of cow and calf sounds emanating from my diaphragm calls as I moved. The idea was to simulate a herd of cows and calves on the go. Elk are very vocal this time of year and can be noisy when crashing through brush in a rush. That was me. A noisy elk herd.

All the cows stopped. Every one of them looked at me as I slowed my pace and stopped in the black shadows. The bull was out of sight, behind a thicket of cedar trees with a handful of cows. I sat on my knees, nocked an arrow and waited. Two minutes later the herd relaxed and continued walking, their single-file line meandering into the trees. When their pace quickened and transitioned to a trot, I raised to my knees and reached full draw. I’d already ranged it. The bull was the last one in the herd. When I let out a sharp cow call, it stopped. The arrow buried in the crease behind the shoulder. The bull staggered into the timber and tipped over.

Read Next: How to Call Elk

Bull Ridge

During one late September hunt in the Rockies, I struggled to find bulls. Then a frost hit. By midnight the mountain was alive with bugling bulls. I didn’t sleep the rest of the night. Up to that point I’d only heard two other bugles.

Daylight couldn’t come quick enough. Less then 200 yards from camp I called in the first bull. A nice 5×5 with an impressive whale tail, it was hard passing on that bull. But distant bugles in the timber kept me moving up the mountain.

It was my first time hunting this area. I had a lot to learn. Over the next hour I called in three more bulls, no shooters. Then I hit a flat covered in young pine trees and alders. Fresh rubs were everywhere. More importantly, so were old rubs. The closer I inspected the rubs, the more I learned. Bulls had been using this area for several consecutive years during the rut. My timing was perfect.

It was a steep climb. I did no calling until reaching the flat. Checking the wind, I drank some water and caught my breath. A few minutes later I checked the wind, again. It was perfect. Consistent and steady. Then I let out a bugle. Three bulls instantly hammered back. Their bugles triggered two more bulls to bugle.

I barely had enough time to nock an arrow by the time the first bull arrived. It sprinted right past me. A second bull did the same thing. That one was a nice bull. I tried stopping it with cow calls but failed. The densely wooded flat was thick with trees and brush. I doubt a bull on the move could even hear my calls. Shooting lanes were tight and short.

The approaching bulls didn’t bother using trails, they just crashed right through the timber. Another series of cow calls brought another bugling bull in my direction. Shattering tree limbs got me shaking. Then I could feel the powerful steps of the bull as it neared. When the heavy breathing deep inside the bull’s chest resonated, I knew it was close.

I drew my bow before seeing him. Given how quickly the others passed, I knew I had to stop this one, for the others would soon wind me from behind. When it popped into view I let out a high-pitched hyper hot cow call. The bull stopped, but instantly pivoted and faced away. I found a narrow triangular window through the tangle of trees, calmed my nerves and threaded the arrow over the right hip of the bull. The fletch vanished.

The fleeing bull sounded like a landslide in the making. Then I heard it stumble and fall over. The woods went silent. The arrow passed all the way through the bull, exiting in front of the left shoulder. The bull-dozed trail was easier to follow than the blood, which there was no shortage of.

Seizing the Moment

I took an aggressive approach to bowhunting elk. Call it impatient, anxious, or inefficient. Call it what you like. I just know I’ve had more close encounters and killed more bulls by being aggressive during specific times when animal behavior favored such moves, versus being timid and waiting for something to happen.

Spend enough time in the elk woods and you learn a lot about the biology and behavior of these regal beasts. Study them closely and you know what fires them up and what causes them to flee, what you can get away with and what you can’t.

Aggressively bowhunting for elk comes with trial and error, but as long as you learn from the blown opportunities, they’re not failures.

Read Next: Where to Hunt for Elk: The 3 States That Still Offer Great DIY Hunts

Failure only comes from giving up. Success may come years later, but remembering all you learn along the way is what the true journey of an elk hunter is all about. And the learning never stops.

For signed copies of Scott Haugen’s many books, visit scotthaugen.com. Follow his adventures on Instagram and Facebook.

Read the full article here