The Ducklegger War: How an Undercover Agent Busted a Massive Ring of Market Hunters and Waterfowl Bootleggers

This story was originally published in the December 1958 issue of Outdoor Life.

At secret rendezvous points in three Midwestern states, they started gathering before dawn. It was September 5, 1958 just four days after Labor Day.

In Illinois they gathered from Peoria to Beardstown along the Illinois River, and near the Mississippi in the vicinity of Quincy; in Wisconsin they gathered between Prairie du Chien and La Crosse; in Michigan they gathered in the St. Clair Flats area within sight of Detroit’s suburbs. There were more than 80 of them. Half were game agents of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or U.S. marshals; the other half were state game wardens.

It was a big aggregation of enforcement officers, one of the biggest ever assigned to a game-law case in the United States. It needed to be. The 80-odd game protectors faced a man-sized job that morning. They carried federal warrants for the arrest of 95 men charged with market hunting or trafficking illegally in wild ducks.

Their plan called for the biggest round-up of alleged violators in the history of the long war Uncle Sam has waged, ever since market hunting was outlawed in 1918, against unscrupulous gunners who kill ducks and geese for sale and wildlife bootleggers who help market them. The Fish and Wildlife Service hasn’t won all the battles in this war, by any means, but this was one they meant to win. They hoped to smash, at one stroke, the whole market-gunning operation in the leading waterfowl centers of the Midwest.

Under federal law, shooting ducks and geese for market is a misdemeanor, not a felony, and most U.S. judges prefer to have such warrants served by daylight rather than at night. So zero hour was set for 6 a.m.

The whole job, as hush-hush as a narcotics raid, had been worked out in detail over a period of weeks by the two men in charge: Charles H. (Chuck) Lawrence, assistant chief of the branch of management and enforcement of the Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, and Floyd H. (Flick) Davis, regional supervisor of enforcement for the North-Central region at Minneapolis. Davis had contacted the chief law-enforcement officer in the conservation department of each of the three states a week before, the first inkling anyone had of what was in the wind, apart from those who were directing the operation, and had been given full cooperation.

On the afternoon before the arrests, state and federal men made a dry run together, locating the homes of the men they wanted, sizing things up, making sure there’d be no hitch. Arresting 95 men in a morning is no small undertaking, especially when some of them have reputations for being fairly hard lads. The officers went about the job quietly, but ready for anything, working in pairs to forestall resistance or trouble.

The raid moved like clockwork. At precisely 6 a.m. they started knocking on doors. The agents found most of their men in bed. Sleep-fogged poachers, who had bragged openly of their outlaw duck killing and predicted that no game warden would ever catch up with them, tumbled out, caught flat-footed. Not one was armed; none offered resistance. Here and there a man argued, but not for long. One, given permission to make a call, phoned the county sheriff—whom he claimed as a personal friend—and asked for advice. He got it, hung up, and said, “O.K., I’m ready to go.”

A few of the men had left for work and had to be gone after. Two happened to be commercial fishermen and were already on the Mississippi lifting nets. That caused only a temporary delay. In less than three hours, 80 of the defendants were in custody. Rounding up the others was only a matter of time. Two or three had moved; one was away on his honeymoon. “He’ll find bad news when he gets home,” a federal agent commented.

Only one of the 95 warrants could not be served. It was for a hunter who was accused of selling 125 ducks to the government’s undercover agent more than a year before. Now he was dead. That left 94 defendants to face federal court. A bootleg ring that Fish and Wildlife officials think may have been slaughtering and selling upward of 250,000 ducks a year in half a dozen Midwest states had suffered a crushing blow.

Few game-law violations are as hard to stamp out. With very few exceptions, the men who shoot for market and deal in bootleg game are not run-of-the-mill violators. They’re game racketeers, in the business for money. They belong to a carefully organized and well integrated ring that operates much like any underworld business. The ring includes men who do the shooting, others who buy and wholesale the birds, still others who deliver them to market. Often it includes operators of shady joints who serve duck dinners at a fat profit. The ring also has its own effective spy and lookout system.

The men who hunt are marshmen who know the country. Those who push and deliver the birds are likely to have helpful political connections. And at all points of the operation, relatives or friends stand ready to pass along tips on the whereabouts of game officers, either for pay or for free.

In many ways the operation resembles bootlegging in prohibition days. The racket is kept going by taverns, night clubs, bars, restaurants, and gambling jointsoften operated by mobsters-where wild-duck dinners can be had at $6 to $7 per duck. Or — surprisingly often — the ultimate consumer is an individual of good standing in his community, who “just wants to put on a few duck dinners for some friends.” Federal agents told me, for example, of a prominent attorney in that class, who regularly buys up to 400 birds a year.

Local officers in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan told me they knew that ducks were being shot for market in the areas where the 94 arrests were made. In many cases they even knew who was doing the shooting. But their best efforts over a period of years had resulted in only an occasional pinch. The ring was too well organized for them to break up.

In the face of such odds, how does Uncle Sam get the evidence on a far-flung nest of commercial gunners and duckleggers?

As in two previous operations — in California in 1954 and Texas in 1956 — this was a one-man job, a tough, dangerous assignment carried out over a period of two years by Tony Stefano, ace criminal investigator of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. His undercover job in California had resulted in the arrest and conviction of 28 men. And in the coastal marshes of east Texas, Tony had put the finger on 56 operators who’d been killing and marketing an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 ducks and geese a year. That story was told in detail in “Texas Man Trap” in OUTDOOR LIFE, December, 1956, shortly after Tony moved to Illinois to tackle the leading market-hunting nests of the Midwest.

Market hunters and duckleggers keep special watch of federal game agents. The federal man isn’t likely to be known in the area where he’s working and violators dread a federal rap. The ring members go to considerable pains to study each federal agent they discover. They make notes of his appearance, the kind of shoes and clothes he wears, and the car he drives. Then they pass the word around. They also make it their business to know where he is at all times, and they have their own ways of finding out.

When Stefano’s operation was going full blast in Illinois, for instance, a squad of federal agents was sent into the area to see whether their presence would dry up the supply of illegal ducks. They arrived about supper time, unaware that Stefano was in the area. Before midnight, while he was calling at the home of a leading market hunter, Stefano was told, “You better lay low for a week or so. Couple carloads of feds pulled into town tonight.” He bought few ducks until the agents moved out. Then business resumed.

How dangerous was Tony’s Midwest assignment? This ring had the usual assortment of tough characters. There was an ex-pug, a labor goon or two, former cops now engaged in shady business, and one man who’d pulled a gun on a federal officer a few years before. There were also quite a few third-generation men, following their fathers and grandfathers in a hard-bitten, outlaw trade.

If they discovered they were dealing with an undercover agent, there wasn’t much chance they’d take it lying down. More than one game warden has been murdered under such circumstances. The least Stefano could expect, if things went wrong, was a rough working over; the worst, an “accident” in a duck blind. There was always the possibility, too, of retaliation gangland style, for some of the men had the right connections to arrange it.

But Tony was used to risks of that kind. The mob he’d smashed in Texas included drunks, gamblers, expimps, and honky-tonk operators. The Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin crowd wasn’t as tough, he told me when the job was done. There was little threatening, less cloak-and-dagger stuff, never any gunplay.

He was threatened only once. In a Wisconsin tavern a man he’d bought ducks from told him, in the presence of two market hunters and two strangers, “If you turned out to be a fed and testified against me in court, I’d kill you on the witness stand.”

“He’ll have the chance,” Stefano says.

Things got a little hairy on one or two other occasions. A ringleader took Tony into a blind in Illinois for a morning’s shoot; four other members were there ahead of them. As they neared the blind the host yelled, “Watch out, boys, I’m bringing in a federal agent.”

That was the first time anybody had hinted at suspicion, and Stefano feigned rage. “What the hell you mean by a crack like that?” he blazed. All the same, he kept his eyes open. There was a pile of ducks in the blind, shot before he arrived. The host killed four in about 10 minutes. Tony shot once, jammed his gun. The market hunter picked four birds off the pile and handed them to him. “Here’s your limit,” he barked. “Let’s get out.”

They did. But when the man got to know Tony better, he bragged that he’d gone back later and helped kill 115 ducks.

One big difference in this Midwest undercover operation was that Tony couldn’t use his own name, as he had in the California and Texas jobs. Since the Texas case had received nationwide publicity, there was little chance that any market hunter would sell a duck to a guy named Stefano. So he’d bought a house in East Peoria under the name of “Marc DeMarco” and moved in with his family. His car registration, driver’s license, and the hunting licenses he bought that fall all bore that name; even his wife and 16- year-old son went under the DeMarco name.

Some amusing things happened as a result. The undercover agent was at a dinner in an Illinois hotspot one night with a market hunter he’d known only a short time. Without warning the man shoved across the table a copy of OUTDOOR LIFE carrying the story of how an agent named Tony Stefano had mashed the Texas ring. Marc proessed complete lack of interest, and went on with his evening paper.

“I could get you 500 ducks a year,” the hunter boasted, “but if the government is going that far to catch us, I’ll have to know you a hell of a lot better before I sell you a bird.”

He relented later, however. And when the warrants were served, he was on the list.

And in Detroit, one of the arrested men, after pleading guilty, confided to U.S. Attorney John Chase that he too had read the story and often wondered what he’d do if he ever ran across Stefano. “I never dreamed I was talking to him everyday,” he muttered.

A safe name, though, isn’t enough. A secret agent needs a “front,” a business that he can pretend to be carrying on while he goes at the real job. In Texas, Stefano had posed as a shady jewelry salesman, not above dealing in hot gems, pushing dope, or procuring call girls. But he decided a respectable disguise was needed this time.

So, as DeMarco, he went to Minneapolis and contacted a manufacturer he knew, Delbert Belden, president of the Louver Manufacturing and Supply Company. He told Belden his story. “I want to be a manufacturer’s representative for you,” he said.

Belden, himself a duck hunter hating market shooting, thought it over. “Know anything about the louver business?” he asked. “No, but I learn fast.”

As a routine safeguard, the company asked the FBI to check DeMarco. When the report came in, he got what he asked for. He spent a few days at the factory and went back to Peoria as a full fledged road representative. Now he had a job, a name, a solid reputation to work on. Flick Davis calls Belden’s contribution one of the most public-spirited things he’s ever known a man in such a position to do.

DeMarco now made the rounds of Illinois towns and called on dealers handling the company’s products. He carried catalogs and the usual paraphernalia. When market hunters phoned the dealers later to check on DeMarco, as happened many times, the answers were always right.

Here’s the story of what followed, as Stefano told it to me in the Fish and Wildlife Service’s regional office in Minneapolis, three days after the arrests were made. It’s the same story he’ll tell on the witness stand in federal court when he testifies against the 94 defendants.

His first buy of illegal ducks was only a penny-ante deal; it takes time to win the confidence of the market. DeMarco had a tip that a used-car dealer in an Illinois town was also a commercial hunter and dealer in contraband ducks, so he made a business call and led the talk around to hunting.

“I’m a poor shot,” he confided, “but I need some ducks to entertain business friends.”

The suspect put his question bluntly and without hesitation. “You want to buy some?”

“Sure.”

The car dealer opened the door and yelled out to a little knot of men on the lot, “Any of you guys got ducks for sale?”

One had. DeMarco clinched the deal, paying $6 for seven ducks of assorted kinds. The ice was broken. That was in October, 1956.

By early November he was making small buys regularly in that area and other leading Illinois duck centers. Later in November, as the market gunners got to know him better, things picked up. A tavern operator sold him 37 birds in one batch. A buy of 42 from a father-and-son team followed, and a day or so later he bought 75 from another tavern man.

DeMarco posed at first as just a salesman with a lot of business favors to do. “I could give my customers a bottle of whiskey or take ’em out to dinner,” he’d explain, “but they can buy them things for themselves. If I give ’em half a dozen ducks, I’m really the fair-haired boy.”

Now, making bigger and bigger buys, he had to invent a fresh excuse.

“I’ve got an uncle that runs a joint up in Chicago,” he told the hunters. “He asked me to bring in all the ducks I can get.”

By the beginning of 1957, things were rolling in high gear. Although the Illinois duck season had closed December 21, that was no handicap. Winter, with the birds concentrated and legitimate hunters out from under foot, was the duckleggers’ best season.

DeMarco made his first buy of 100 in a single lot in January, from an Astoria man. The same man supplied another batch of 100 a couple of weeks later, and followed with a sale of 120, delivering them to Marc’s house. The undercover agent knew now he had passed the test. He was posing openly as a wholesale dealer, a member of the ring, and even the ultracagey big-time operators had accepted him. “You don’t need to be afraid of DeMarco,” one said in introducing him to another.

“I’ve had the hoods in Peoria check him and he’s O.K.”

When the ducks pulled out of Illinois on the northward flight in April, 1957, the illegal sales had mounted to 2,000.

In buying the ducks, Marc had been painstakingly careful to avoid two things: asking any hunter to kill ducks for him, or ordering a specific number at a given time. He just bought whatever was available, whenever they were offered. In court, the plea of entrapment by a federal agent is the one almost unfailingly used by duck bootleggers.

“I wouldn’t ever have sold a duck, your honor,” they’ll whine, “but I thought this guy was a friend. He begged me to get him 20 mallards, so I went out and shot ’em as a favor to him. I never did anything like this before.”

That was the alibi offered by every member of the Texas ring who chose to stand trial, but it did no good. DeMarco had gained too much experience in undercover work to lay himself open to such a charge. Whenever possible, he made three of four separate buys from each Midwest suspect-to forestall any plea of entrapment-and then avoided that man and moved to another. He hunted repeatedly in season with the market gunners, watched them kill ducks wholesale, but contrived never to shoot more than the limit himself, although often urged to do so as a test. “I’m a lousy shot,” he’d alibi with a chuckle.

He also managed to jam his gun at convenient times, and refused repeated invitations to take part in illegal hunts. “Can’t afford it,” was his excuse. “My boss would fire me in a minute if I got caught.” In one instance he declined to shoot after hours with a hunter who’d just sold him 61 ducks, whereupon the poacher refused to sell him another bird. But by that time it was too late.

When the fall flight poured south in 1957, the masquerading louver salesman was back in the Illinois duck towns, more eager than ever to get birds in big lots. Buys of 30 to 100 became common now, and DeMarco began to get a clearer picture of how many ducks were being siphoned illegally to markets in St. Louis, Peoria, Springfield, and Chicago. Later he was to find that a big market flourished in Detroit as well.

He bought 300 in one lot in Quincy, Ill. He found a hunter who had 10 gunny sacks of down stashed in his basement ready for sale, accumulated in a season and a half of illegal operation. One Illinois dealer offered to guarantee him 10,000 ducks a season. DeMarco backed away, saying he couldn’t use that many. And after the case broke, he told me he was convinced there were at least half a dozen men in the ring who could have filled orders of that size.

How were the birds taken in such numbers? Some were netted or trapped, but most of them were shot. Bait was used, both to lure ducks into traps and to concentrate them on ponds and potholes. In some cases, after ice came, the market hunters resorted to bait and decoys.

There was less mass killing than was uncovered in California and Texas, where hunters often crept up at night on flocks of thousands, raking them with guns holding up to 14 shells in extension magazines. Nothing like that was found in the Midwest. But a crew of three or four crack shots, shooting unplugged guns from a blind on a baited pond could knock off as many as 200 ducks at a time. They raked the sitting birds with shot, then poured in more lead as the ducks rose in a cloud. Most of the shooting was done at daybreak. The rule was, “Blast ’em, and make a fast get-away.”

There was one curious sidelight on the trapping of ducks. Hotspots serving illegal duck dinners want to make sure they’re getting wild birds, not mallards raised on a game farm. So many of the trappers would put four or five trapped birds into a gunny sack, then back off and fill them full of lead.

By 1957 the trail lead across the Illinois line into Wisconsin. DeMarco started making calls around Prairie du Chien. “You can get all the ducks you want for two bucks apiece,” he was told. Before long he’d bought 38 ducks from one hunter, then 42 from the man’s brother. By the spring of this year, he’d accumulated evidence implicating 10 Wisconsin men.

Again in the fall of ’57, acting on tips from other federal agents about market-hunting activities in the St. Clair Flats area, DeMarco moved into Michigan. It didn’t take long to get a toe in the doorway. Before the end of October he’d bought 23 ducks from a gas-station operator in the area, and 30 from a hunter on Harsens Island. A month or so later he followed up with buys of 46 from a retired Detroit cop, 60 from another member of the ring, and 61 from a third.

Business boomed. A total of 1,341 ducks passed into the agent’s hands. And when round-up day arrived, warrants were served on 21 defendants around the Flats. Jasper Poole, running a grocery store at Algonac, Mich., told DeMarco he had a ready source among some Natives on Walpole Island, on the Canadian side of Lake St. Clair. They killed the ducks and brought them over for 50 cents to $1 apiece. Poole got $1.25 to $1.50. Charged with aiding and abetting the sale of waterfowl, Poole pleaded guilty in Detroit the day he was arrested.

Michigan conservation officers say many of the birds sold around St. Clair Flats were killed by Natives on Walpole Island.

The individual buys in Michigan and Wisconsin weren’t so big as those in Illinois, but that didn’t indicate a small operation. It takes a while to find out who the wanted men are, get their confidence, and start dealing in a big way. Says DeMarco: “If I’d operated one more year, I’d have been swamped with ducks in all three states.”

It was in November of 1956 that he made a small buy of more than ordinary interest in Quincy, Ill. It was a deal involving only seven ducks, but they came from a city fireman. Next there was a buy of 10, then 42. Finally the total reached 486 birds, supplied by four members of the Quincy fire department. When the time came to serve warrants, federal officials were reluctant to deplete the force by taking the four men off duty all at one time, so they called on the chief, told their story, and offered to let the four appear voluntarily, as they could be spared. There was no delay about their showing up.

By spring of this year, DeMarco had bought a total of 5,141 ducks in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. He figures that was less than five percent of the ducks that went to market from the areas he’d worked.

He had also bought five geese, 10 pheasants, one deer, and 98 pounds of black bass and crappies, taking the pheasants, deer, and fish to avoid suspicion when they were urged on him. He’s convinced the traffic in nonmigratory game in many Midwest areas would amaze sportsmen. He was offered deer, quail, pheasants, and rabbits repeatedly, but refused to buy unless the market gunners showed resentment and charged him with being interested only in migratory birds. That was a danger signal he dared not ignore.

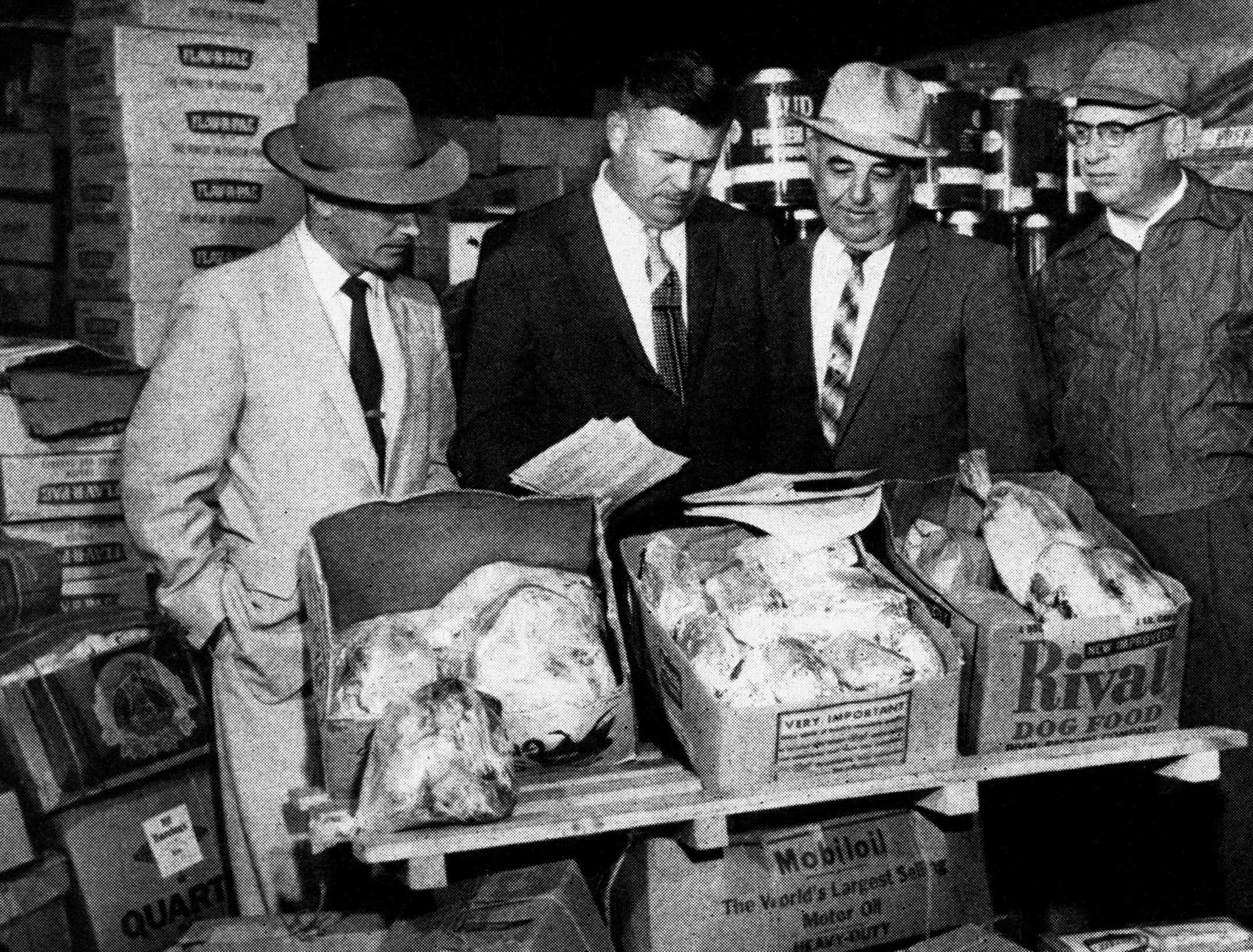

How had he disposed of his huge stockpile of illegal birds? By turning them over at night, as fast as he bought them, to trusted regular agents of the Fish and Wildlife Service, in secret meetings on lonely country roads and in back alleys and cemeteries. The birds were tagged for identification, put in cold storage, and held for evidence. There are frozen ducks to back every one of the 94 warrants.

The job was now done, the man trap ready for springing. The Fish and Wildlife Service decided to wait until early fall, just before duck season, in the belief that such timing might discourage market hunting in other parts of the country.

In August of this year, the house in East Peoria was sold, and the DeMarco family vanished. A month later the officers struck, the story broke, and the duck bootleggers learned something new about a “louver salesman.”

“I never sold a duck to anybody named Stefano,” one of them wailed indignantly to the officers who arrested him. Then he thought it over a minute. “But I guess I did sell a few to Marc DeMarco,” he confessed, crestfallen.

Read Next: I Was the Youngest Duck Poacher in Saskatchewan

What penalties do these men face if convicted? That will be up to the judges, of course, but it’s unlikely they’ll get off lightly. Once a U.S. judge is convinced from the evidence that commercial hunting is involved and that he’s dealing with wildlife racketeers, he isn’t inclined to be lenient. The kingpins in the Texas ring were fined up to $500, served jail terms as long as six months, and (maybe the harshest punishment of all for such men) lost the right to hunt waterfowl for three years. Sentenced in 1956, they’re still ineligible to enter a duck blind.

The evidence I’ve cited here makes federal game officials think the hunters were marketing at least 250,000 birds a year. From the viewpoint of sportsmen, you can’t put a price tag on a wild duck, but surveys indicate that ducks killed legally cost around $8.16 apiece, taking everything into account. Duck hunters agree they’re worth what they cost. That means the duckleggers were slaughtering around $2,000,000 worth of waterfowl a year. To break up a racket of that scope at a cost of less than $50,000 is good business.

Where do we go from here? Market hunting has been hit hard in three sections of the country — California, Texas, and now the Midwest. But federal authorities are convinced it’s still flourishing in other major duck centers.

How can it be knocked out? How can the ducks be saved for honest hunters who buy licenses and stamps and follow the rules?

To begin with, as Chuck Lawrence points out, it would be a big help if otherwise law-abiding people who buy ducks for themselves and their friends, or order illegal game dinners in shady spots at fancy prices, would reform. He’s dead right, of course, but as prohibition taught us, there isn’t too much hope of drying up an outlaw market by voluntary action of that kind.

The surest way might be to expand the Fish and Wildlife Service’s undercover program. Presently the entire force of U.S. game agents consists of only 128, pitifully few when you consider the vast size of the country they must cover. More enforcement agents, together with additional undercover operators, should do a lot toward saving waterfowl for the guns of legitimate hunters.

If the Service, which operates on a regional setup, had a Tony Stefano or two working in each of its six regions, duck bootlegging would soon lose its lure. Such a program, in co-operation with state game departments, could go far to curb the traffic in other game as well, and there’s no doubt that sportsmen would welcome it.

Meanwhile, here’s a tip to market hunters everywhere: At a press conference in Minneapolis last September, a reporter asked Lawrence, Davis, and Stefano if they had any plans for the future. “Our undercover work will go on,” they said firmly.

Read the full article here