The Guns (and Soldiers) That Won the American Revolution

This story, “Guns of the American Revolution,” appeared in the July 1976 issue of Outdoor Life.

“This province has raised 1,000 riflemen, the worst of whom will put a ball through a man’s head at the distance of 150 or 200 yards; therefore advise your officers who shall hereafter come out to America to settle their affairs in England before their departure.”

This cryptic note, written by a resident of Philadelphia and published by the London Chronicle in August of 1775, no doubt had a sobering effect on British bluebloods who believed that thrashing the Colonial rubbish would be jolly sport.

In December of that same year, another note, this one from a minister in Maryland, reached the Earl of Dartmouth: “Rifles, infinitely better than those imported, are daily made in many places in Pennsylvania, and all the gunsmiths everywhere are constantly employed. In this country, my lord, the boys, as soon as they can discharge a gun, frequently exercise themselves therewith, some a-fowling and others a-hunting… In marching through the woods, one thousand of these riflemen would cut to pieces ten thousand of your best troops.”

Such items, widely published in America and Europe, were often pure fancy. But just as often they were completely honest portrayals of the American and his rifle.

Just how good was the marksmanship of the rebels? Were the graceful “Kentucky” rifles (made mostly in Pennsylvania) as accurate as legend has it, and was the Kentucky truly the arm that won our independence? Perhaps most important of all, how did American shooting compare with the best the British and Hessians had to offer?

The accuracy of Revolutionary American sharpshooting is no myth, at least not by the standards of that day. Some of the feats of marksmanship demonstrated by the keen-eyed frontiersman were totally incomprehensible to most Europeans.

One very reliable eyewitness account is the report of Gen. Victor Collot, a French military officer who observed the Americans for his government. He encountered a band of Kentuckians and had this to say:

The accuracy of Revolutionary American sharpshooting is no myth, at least not by the standards of that day. Some of the feats of marksmanship demonstrated by the keen-eyed frontiersman were totally incomprehensible to most Europeans.

In actual skirmishes with the British forces, the riflemen provided telling examples of their skill. In one instance a troop of Englishmen were pinned down by what they feared was a Colonial sharpshooter firing from a grove of trees some 250 yards away. A line officer who exposed about half of his head to take a peek never knew what hit him.

One of the most illuminating descriptions of American marksmanship comes from a contemporary account by George Hanger, a British major: “Colonel Tarleton and myself were standing a few yards out of a wood, observing the situation of a part of the enemy which we intended to attack. There was a rivulet in the enemy’s front, and a mill on it… Our orderly-bugler stood behind us about three yards, but with his horse’s side at our horses’ tails. A rifleman passed over the milldam, evidently observing two officers, and laid himself down on his belly; for in such positions they always lie, to take a good shot at a long distance. He took a deliberate and cool shot at my friend, and me, and the bugle-horn man. Now observe how well this fellow shot. It was in the month of August, and not a breath of wind was stirring. Colonel Tarleton’s horse and mine, I am certain, were not anything like two feet apart; for we were in close consultation… A rifle ball passed between him and me, looking directly at the mill I observed the flash of powder. I directly said to my friend, ‘I think we had better move on, or we shall have two or three of these gentlemen shortly amusing themselves at our expense!’ The words were hardly out of my mouth when the bugle-horn man behind me, and directly central, jumped off his horse and said, ‘Sir, my horse is shot.’ The horse staggered, fell, and died… Now, speaking of this rifleman’s shooting, nothing could be better… I can positively assert that the distance he fired from at us was a full 400 yards.”

Major Hanger’s account is especially important because he was a noted English authority on arms and marksmanship. If he was amazed at the quality of that shot, we can have it on good authority that it was exceptional for the day. But we also have to consider that the marksman did miss the English officers and hit only a horse. That considered judgment is not consistent with contemporary American newspaper claims of man-killing accuracy out to 700 yards. On the other hand, it is precisely consistent with some accuracy experiments with muzzleloading rifles I carried out 12 years ago.

Using high-quality barrels, powder, and balls — no doubt considerably better than those used in the Revolution — I tested grouping at 100, 200, and 300 yards. I didn’t do any testing at 400 yards, but judging by the results at the shorter ranges, I could have hit a horse at that range. But I could not have hit a man more than twice out of five shots at 400 yards.

Facts notwithstanding, the two most famous shots of the War of Independence were fired by Americans using Kentucky rifles. One bullet killed General Frazier at the battle of Saratoga. It is said to have been fired by Timothy Murphy, a well-known marksman. The other famous shot from a Kentucky rifle, said to have been fired from over 400 yards, killed Col. Patrick Ferguson at the great rifle shoot known as the Battle of Kings Mountain. Ferguson was a famous rifle marksman himself, and he invented the Ferguson rifle, an early and quite successful breechloading flintlock rifle.

These were notable achievements in terms of individual marksmanship and rifle performance, but such feats gave rise to dozens of myths that glamorized the frontier rifleman but had the effect of demeaning the role of the line soldiers of the American Army, who were armed with smoothbore muskets. One thorny myth is that the American Army consisted of sharpshooters who sniped at formations of British troops with rifled arms. In truth, less than 3 percent of the American soldiers were equipped with rifles. Except for the Battle of Kings Mountain and the retreats from Lexington and Concord, no important engagements of the war were characterized by direct, aimed fire by sharpshooters.

One very real advantage of the rifleman was purely psychological. During the French and Indian Wars, the British fought side by side with the Colonials and witnessed the incredible skill of some Americans with their long rifles. The stories were carried back to England, and no doubt were exaggerated with each telling. But by the time the Revolution was well under way, the American sharpshooters had almost thrown away this valuable psychological edge. Furnished with unprecedented and free amounts of powder and lead, the frontiersmen engaged in their favorite pastime-sniping at anything resembling a redcoat, no matter what the range. No doubt this hail of rifle fire, sometimes at impossible ranges, resulted in occasional hits, but the ratio of hits to misses was so low that our military leaders felt we were in peril of losing our desperately needed psychological advantage. It was necessary for Gen. Lighthorse Harry Lee to order a Colonel Thompson to do something about the wild, ineffectual shooting being done by his company of sharpshooters.

“It is a certain truth,” Lee wrote to Thompson, “that the enemy entertains a most fortunate apprehension of American riflemen. It is equally certain that nothing can contribute to diminish this apprehension so infallibly as a frequent ineffectual firing. It is with some concern, therefore, that I am informed that your men have been suffered to fire at a most preposterous distance. Upon this principle I must entreat and insist that you consider it as a standing order that not a man under your command is to fire at a greater distance than a hundred and fifty yards, at the utmost; in short, that they never fire without a moral certainty of hitting their target.”

The British were indeed so apprehensive about the moral effect rifle fire might have on their troops that they made specific bargains for German jaegers (sharpshooters) when hiring mercenary troops from the German Princes. They hoped to cancel out the propaganda value of the American rifleman by using German sharpshooters. Though they are seldom mentioned in histories, the Hessian marksmen were surprisingly effective. Ironically, some American leaders eventually learned about the effective use of well-aimed rifle fire in combination with a military assault only because the lesson was taught by the Hessians.

It has often been written that the Kentucky rifle had one great advantage over European rifled arms. The Kentucky utilized a patched ball to engage the rifling, while the Europeans, it is still widely believed, pounded the lead ball into the rifling with an iron ramrod and a mallet — a slow and noisy process. This belief is almost total error. Patched-ball rifle loading was well known in Europe in the 1770’s. Specimens of jaeger rifles in my own collection as well as others I have examined were definitely designed and rifled for a patched ball. Legend notwithstanding, Hessian and British sharpshooters had rifles that they loaded as quickly and as easily as those of the American frontiersmen, and their rifles were at least as accurate as ours.

After encountering some rifle equipped enemy soldiers at the siege of Yorktown, an American recorded the incident with obvious surprise and dismay: “… a few shot were fired at different times in the day and about sunset from the enemy’s re-doubts — we had five or six men wounded. The execution was much more than might have been expected from the distance, the dispersed situation of our men, and the few shot fired.”

Maj. George Hanger, the English officer who professed amazement at American marksmanship, nonetheless had a poor opinion of the riflemen in battle. He wrote: “Riflemen as riflemen only, are a very feeble foe and not to be trusted alone any distance from camp; and at the outposts they must ever be supported by regulars, or they will be beaten in and compelled to retire… meeting a corps of riflemen. namely riflemen only, I would treat them the same as my friend Colonel Abercrombie… treated Morgan’s riflemen. When Morgan’s riflemen came down to Pennsylvania from Canada, flushed with success gained over Burgoyne’s army, they marched to attack our light infantry, under Colonel Abercrombie. The moment they appeared before him he ordered his troops to charge them with the bayonet: not one man out of four [American riflemen] had time to fire, and those that did had no time given them to load again, the light infantry not only dispersed them instantly but drove them for miles over the country. They never attacked, or even looked at, our light infantry again, without a regular force to support them.”

The “regular force” was armed with quick-loading smoothbore muskets and with bayonets. Lt. Col. John Simcoe, commander of the famed Queen’s Rangers, wrote:

The tide of the war rose in Washington’s favor as his troops became more experienced and proficient in just this type of fighting. The hero of the American Revolution was really the stubborn, foot-slogging regular soldier who was armed with a musket and a bayonet and a bitter resolve.

And another British officer had the following comments in the Middlesex Journal: “… about twilight is found the best season for hunting the rebels in the woods, at which time their rifles are of very little use; and they are not found so serviceable in a body as musketry, a rest being requisite at all times, and before they are able to make a second discharge, it frequently happens that they find themselves run through the body by the push of a bayonet, as a rifleman is not entitled to any quarter.”

Interestingly, this same general opinion was held by the American leaders as well. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne went on record as never wanting to see another rifle, at least not a rifle without a bayonet, and he would still have preferred muskets. And when Maryland offered to send a rifle company to join the Continental Army, the Secretary of the Board of War declared that while they needed the men, they didn’t need riflemen. They preferred men armed with muskets, and if it were within the means of Congress, the existing rifles in the line would be replaced with muskets.

All of this may seem to be an unnecessarily harsh indictment of the beloved Kentucky rifle, but it isn’t, for at least two very good reasons.

Popular conceptions to the contrary, the gracefully slim and artistically ornamented Kentucky rifle with its gentle curves and bright inlays did not come into existence in any numbers until after the American Revolution. Its golden age of manufacture ran from about 1790 until 1820. The “Kentuckies” of Revolutionary days were of rather stark design with straight, musketlike lines and little or no decoration other than a brief bit of carving and a plain patchbox. In fact, many of the rifles actually of the revolutionary era would scarcely be identified as a true Kentucky.

Another remarkable feature of the Kentucky rifle is that many of them weren’t really rifles at all. These arms were smoothbores, but they were loaded with patched balls. With a smoothbore barrel, multiple-ball or even shot loads could be used effectively, thus making the gun more versatile than a rifle. In a careful survey of Kentucky rifles, fewer than half were found to have rifled barrels!

When I was a school lad I learned my history lessons well and enjoyed nothing more than a well-told yarn about how intrepid marksmen ambushed a band of hated British and then vanished into the forests and swamps. But the history books also had a lot to say about an imperious, hard-driving taskmaster named General Von Steuben, who taught our army how to drill, march, and fight in true European style and whipped them into well-disciplined formations. This puzzled me to no end, because I couldn’t see any point in learning to drill and execute formal maneuvers in open fields if the army really fought from behind logs and trees.

The truth is that most of the battles of the Revolution were fought according to established European concepts. It is equally true that the tide of the war rose in Washington’s favor as his troops became more experienced and proficient in just this type of fighting. The hero of the American Revolution was really the stubborn, foot-slogging regular soldier who was armed with a musket and a bayonet and a bitter resolve.

The English leaders who came out to America were of the opinion that the Revolution would be squashed simply by demonstrating British might. They believed that the Americans were like the lower classes of Europe and only needed a good lesson from those in authority.

This mistaken notion soon gave way. No less a British officer than General Gage himself soon changed his opinion of the Americans and wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth: “The trials we have had show the rebels are not the despicable rabble too many have supposed them to be.” What kind of men were these that so impressed General Gage? How were the battles fought?

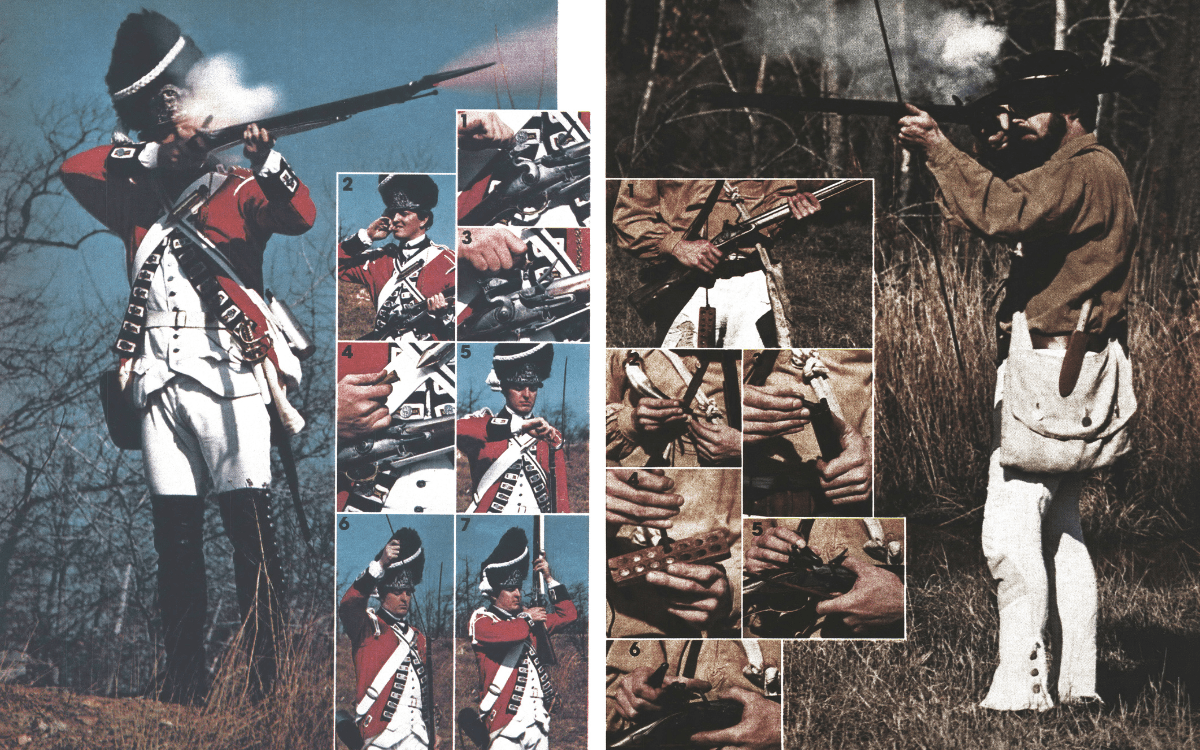

The primary battle tactic of the era was simply to march in shoulder-to-shoulder ranks toward the opposing forces. When a seemingly murderous range was reached — sometimes as close as 60 yards — the troops fired their smoothbore muskets into enemy ranks. After firing, the first rank would kneel or step to the rear to give the second rank of soldiers a clear shot. A third rank of men stood waiting to fill the places of fallen comrades. Several volleys might be fired, and a bayonet charge was usually the last stage.

Under those circumstances, two factors were vital. The soldiers had to be well trained, well disciplined, and brave enough to stand their ground. They also had to be quick about reloading their guns so that volley after volley could be fired.

With practice, a soldier could load a smoothbore musket and fire about four shots per minute. This was considerably faster than a man could manage with a rifled barrel, which, for best accuracy, required a fitted patch around the ball, and the use of a ramrod before every shot to force the patched ball firmly down on the powder. With a smoothbore musket, the ball was usually rammed down on the powder only for the first shot. Thereafter the soldier simply dropped or even spat the loose-fitting ball into the muzzle, and it fell down the tube.

Though the short distances at which units fired at each other seem absolutely suicidal, the carnage was hardly absolute. Smoothbore muskets were notoriously inaccurate, and some of them didn’t even have sights. Remember that they were almost always fired at whole units of enemy soldiers, not at individuals. The best description of the accuracy comes, once again, from contemporary arms authority Maj. George Hanger:

Doctors reported wounds made by rusty nails and odd scraps of metal, and General Howe even accused Washington of allowing his troops to use such murderous projectiles as two bullets fastened to either end of an iron nail.

The small arms of the American Army (not including pistols carried by officers) can be divided into four categories: British “Brown Bess” muskets, French Charleville muskets, American-made “Committee of Safety” muskets, and a rag-tag of shoulder weaponry that included rifles.

The common Brown Bess musket had been the mainstay of English forces since the first quarter of the 18th Century. Since the time of the French and Indian Wars (1756-1763) it had also been the more or less standard arm of Colonial forces. The most common, infantry version of the Brown Bess had a very large flintlock mechanism and a 46-inch barrel of about .75 caliber. The standard load for the Brown Bess was a lead ball ranging somewhere between .687 to .700 of an inch in diameter that weighed 500 grains. This ball was propelled by six drams (163 grains) of black powder. The muzzle velocity was 1,200 to 1,300 feet per second. The undersize ball made loading speedier because it was necessary only to drop the ball down the barrel, and the soldier could continue loading and firing even after the bore was heavily coated with powder residue. The space between the bullet and the barrel wall was known as “windage” and contributed greatly to the arm’s lack of accuracy. The nickname “Brown Bess” comes from the rust-brown coloring of the metal parts.

The French-made Charleville musket used by the American forces was superior to the Brown Bess. The 1763 model, which was the version most used in America, had a .69-caliber smoothbore barrel and was 59 ½ inches overall in length and weighed 9 ¾ pounds. With its improved or reinforced hammer and other refinements, it was probably the best, most reliable musket of its time.

The Colonies had few arms and no arsenal or armories at the beginning of the Revolution, so muskets were made by several small firms. In November 1775 the Continental Congress established guidelines and specifications of the procurement of what was to be known as Committee of Safety Muskets. They called for: “good fire locks, with bayonets, each fire lock to be made with a good bridle lock, ¾ of an inch bore, and of good substance at the breech, the barrel to be three feet eight inches in length.” The American musket was a close copy of the British Brown Bess.

Privately owned arms were sometimes remarkably similar to military muskets, especially the Brown Bess, and some of them even had a bayonet stud. There are too many types to describe here, but apparently this is exactly the weapon used by many Colonists at Bunker Hill. According to eyewitness accounts, many weapons used there were not rifles, but they were not equipped with bayonets either. Many of these pieces were later altered for bayonet attachment and were used by their owners throughout the war. Supposedly, the Continental soldier received extra pay if he brought his own weapon when he enlisted.

Smoothbores were often loaded with more than one projectile, or even a handful of shot. A charge of “buck and ball” consisted of a full-size ball plus three buckshot, a common military load in both armies. Sometimes balls were split or quartered so as to send more projectiles flying, and both sides accused the other of “dirty tricks.” Doctors reported wounds made by rusty nails and odd scraps of metal, and General Howe even accused Washington of allowing his troops to use such murderous projectiles as two bullets fastened to either end of an iron nail. As a matter of fact, Washington was keen on getting as much death and destruction out of every round of musket fire as could be managed, and he ordered that his men load “…according to the strength of their pieces.” In other words, he wanted them to cram in as much powder and projectiles as possible, short of blowing up the weapons.

Read Next: Why Was the Legendary Kentucky Rifle Such a Success?

On the bottom line, the equipment used was not very important in the final outcome of the war. It was musket against musket, and the rifle had very little impact. The American soldier — his resourcefulness, his bravery, his bitter determination — was the key to victory. The Continental soldier was more enthusiastic about killing redcoats and Hessians than they were about killing him. The foreign troops had very little they could gain by the campaign.

The predicament of the rebels, on the other hand, was neatly summed up by an Englishman, Winston Churchill, over a century and a half later: “If you want to learn the game, play for more than you can afford to lose.” The Americans had much to lose.

Read the full article here