Supreme Court weighs religious liberty dispute over public funding for Catholic charter school

The Supreme Court offered clear divisions Wednesday in a religious liberty case involving public education and whether religious charter schools can receive taxpayer funding.

At issue is whether providing public money to a faith-based educational institution violates the First Amendment’s separation of church and state mandate.

In more than two hours of wide-ranging oral arguments, the high court appeared divided along ideological lines, with a majority prepared to allow St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School in Oklahoma City to become the first such religious charter school in the country.

LIBERAL SUPREME COURT JUSTICES GRILL RELIGIOUS INSTITUTION IN LANDMARK SCHOOL CHOICE CASE

The appeal comes amid a renewed pitch in some Republican-led states to bring a greater religious presence to public education.

The conservative high court in recent years has, in select cases, allowed taxpayer funds to be spent on religious organizations to provide “non-sectarian services” like adoption or food banks.

In the courtroom public session, the justices debated what limits on curriculum supervision and control would be placed on the religious charter school, if its contract with the state was allowed to move forward.

“Our [prior] cases have made very clear,” said Justice Brett Kavanaugh. “You can’t treat religious people and religious institutions and religious speech as second class in the United States. And when you have a program that’s open to all comers except religion, no, we can’t do that. We can do everything else. That seems like rank discrimination against religion. And that’s the concern.”

BIDEN-APPOINTED FEDERAL JUDGE KEEPS BLOCKING TURMP ADMIN FROM NIXING FUNDING FOR LAWYERS FOR MIGRANT CHILDREN

“All the religious school is saying is don’t exclude us on account of our religion,” Kavanaugh added.

But others on the bench worried about government entanglement in approving some religious charter schools, and not others, potentially favoring one faith over another.

“What you’re saying is the free exercise clause trumps the essence of the establishment clause,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor told the attorney for the state’s charter school board. “The essence of the establishment clause was, ‘We’re not going to pay religious leaders to teach their religion.'”

The Constitution’s First Amendment says, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett was not on the bench and is recused in the case. She offered no public explanation of why.

If the court divides 4-4, the ruling below holds, with the charter school losing its appeal.

The vote of Chief Justice John Roberts may be key. He asked tough questions of both sides.

At one point, Roberts noted of the current dispute: “This does strike me as a much more comprehensive involvement,” by the state than prior cases dealing with “fairly discrete” public money going to religious groups, such as tax breaks and private school tuition credits.

In an unusual split within the Oklahoma government, the state’s governor, head of public education, and the statewide charter school board are all backing St. Isidore.

But Attorney General Gentner Drummond sued to block the approval of the school’s state charter, calling it an “unlawful sponsorship” of a sectarian institution, and “a serious threat to the religious liberty of all four-million Oklahomans.”

He has the backing of some GOP state lawmakers and parents’ groups, who argue that funding parochial charter schools would drain resources from public education – especially in rural areas already struggling with limited funding.

When it signed a contract with the state charter school board in 2023, St. Isidore – formed as a nonprofit corporation by the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa – agreed it would be free and open to all students “as a traditional public school,” and would comply with local, state and federal education laws.

But in its application to the charter board, it also indicated, “the School fully embraces the teachings” of the Catholic Church and participates “in the evangelizing mission of the church.”

Shortly after Oklahoma’s highest court ruled against it, the school said it remained “steadfast in our belief that St. Isidore would have and could still be a valuable asset to students, regardless of socioeconomic, race or faith backgrounds.”

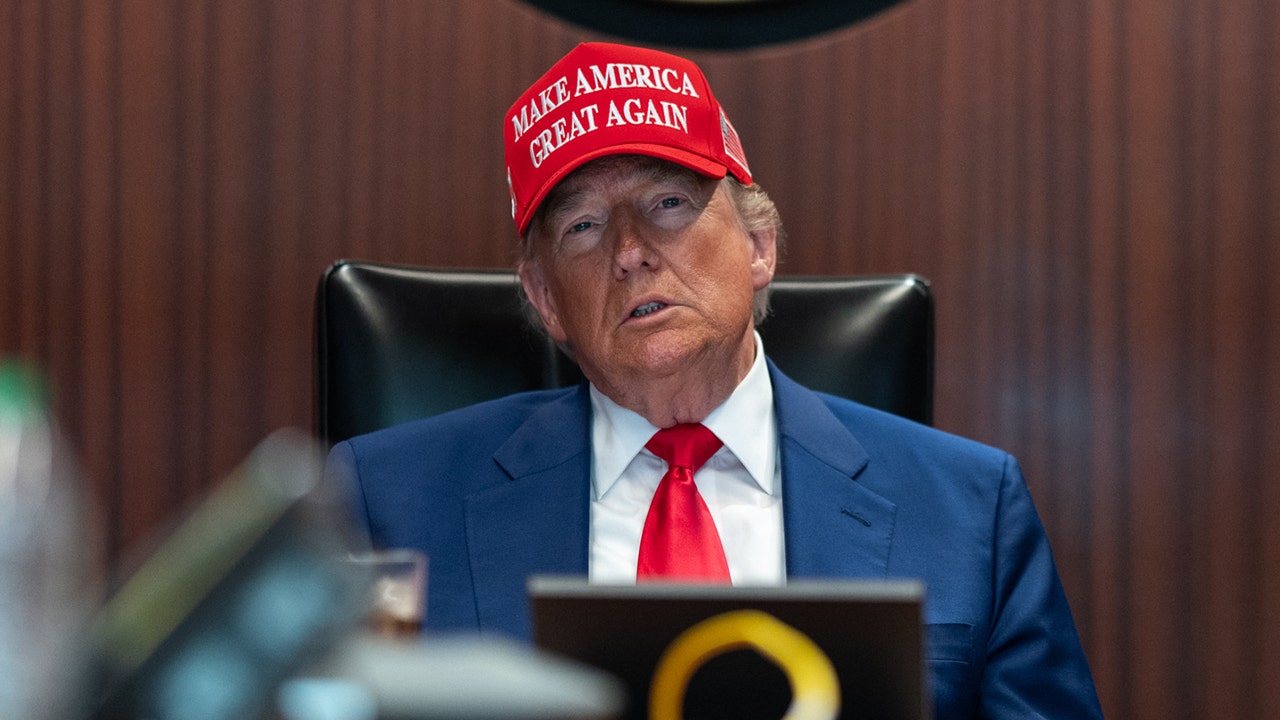

The Trump administration is supporting the school.

Some Catholic sources note the namesake seventh-century archbishop and scholar is now known as the patron saint of the internet, given the title by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

Much of the high court oral arguments turned on whether St. Isidore – a K-12 online school – is public or private in nature.

The distinction is important, since charter schools in Oklahoma are considered public, free and openly accessible to all. That is true in the 46 states – plus the District of Columbia – where charter schools operate.

The Supreme Court has previously said states may require public schools be secular, but also cannot prevent private religious institutions from public benefits and contracts.

The issue now is whether those precedents apply to charter schools.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said charter schools are “a creation and creature of the state.”

Justice Elena Kagan said contracts signed by schools like St. Isidore have basic requirements to meet state classroom standards, with state oversight.

“I’ve just got to think that there are religions that are going to have no problems dealing with all the various curricular requirements and religions that are going to have very severe problems dealing with all the curricular requirement,” she said.

“I’m suggesting to you is this notion that the state can do this while still maintaining all its various curricular requirements. I mean, either that sort of fantasy land, given the state of religious belief and religious practice in this world or if it’s not, it’s only because what’s going to result is treating, shall we call them majoritarian, religions very differently from minority religions,” said Kagan.

But Justice Clarence Thomas noted: “The argument that St. Isidore and the board are making is that it’s a private entity that is participating in a state [charter] program. It was not created by the state program.”

Justice Samuel Alito was more pointed, telling Gregory Garre, lawyer for the state, “This whole position that you’re defending seems to be motivated by hostility toward particular religions.”

Department of Education figures show about 4m illion schoolchildren – or 8% of the total – are enrolled in an estimated 7,800 charter schools, which operate with greater independence and autonomy than traditional public schools. Oklahoma has more than 30 public charter schools serving about 50,000 students.

Last June, Oklahoma’s top education official separately mandated the Bible be incorporated into lesson plans for grades 5-12, and the Holy Scripture be placed in every classroom. And in Louisiana, there is a requirement that the Ten Commandments be posted on public school property. Both policies are facing legal challenges.

Six members of the current Supreme Court attended Catholic schools in their youth, and many of their own children attend or attended private schools, including religious-based institutions of learning.

The consolidated cases are Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond (AG OK) (24-394) and St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School v. Drummond (AG OK) (24-396).

A ruling is expected by early summer.

Read the full article here