The Controversy of the Hinkley Buck, the Heaviest Deer Ever Killed in Maine

This story, “Mystery of The Hinkley Deer,” appeared in the August 1969 issue of Outdoor Life.

I saw the buck alive only the one time, and he was dead a minute after I caught sight of him. The last thing I suspected right then was that I’d never hear the end of him as long as I lived. But even in that first brief glimpse, with him coming through the brush like a runaway express train, I found it hard to believe my eyes. I hadn’t dreamed that such a whitetail could be found anywhere in the Maine woods, and I had hunted there for more than 40 years.

It was a wet morning in early November of 1955. My wife Olive and I were hunting northwest of the town of Bingham, on the Kennebec River below Moosehead Lake and about 60 miles upstate from Augusta, where we lived at the time.

I was 59 then, working as a lumber grader at a planing mill in Augusta. Now, at 73, I am retired, and Olive and I live at North Anson, on the Kennebec south of Bingham.

I’ve lived in Maine all my life, and I started to hunt deer when I was 16. At the time of this hunt I could look back over 36 falls without recalling one when ei ther my wife or I failed to get a deer. And in many of those years both of us had scored.

My job didn’t include vacations with pay, and we lumber workers didn’t get paid for any time lost to stormy weather. So I didn’t feel that I could afford to take a week off for deer hunting. But on holidays and whenever it rained or snowed, I headed for the woods.

I came home from work on the first Friday night of November that year, after two days of storm (I had put in my time piling lumber), and decided from the looks of the weather that Saturday was going to be a day of layoff. Olive and I would go hunting.

My son Philip, 33 then, and his wife Madeline drove into the yard after supper. They had come from their home in South Portland. Philip didn’t have to work the next day either, and they had brought their guns and hunting togs along. We set the alarm for 3 a.m. and turned in.

Saturday morning was wet and dark, with misty rain still falling — exactly the conditions I like for deer hunting. At such times a man can move through the thickest cover with almost no noise. We ate a good solid breakfast — bacon, eggs, toast, doughnuts, and coffee — headed north, and reached Bingham just at break of day. Fine rain was still coming down, and everything looked good.

We’d start in the country west of Fletcher Mountain. Very few of the mountains there are higher than 4,000 feet; most of them are under 3,000. I suppose Western hunters would call them hills. But they’re mountains to us. Mostly they go up in terraces and the slopes are laced with small brooks. You climb, come out on a flat bench, then climb again.

Now and then you can catch a deer feeding on the flats in the early morning or shortly before dusk, but when they bed down for the day it’s usually in a thicket or on some high spot, often near the very top.

We split up, Philip and Madeline going one way, Olive and I another. My wife and I found an old tote road bordered with cuttings, and we hunted along it for an hour. There was plenty of deer sign, but none of it was fresh, and we turned onto a truck road that would take us down to the valley and across to the opposite range.

We had walked only a short distance when a jeep came along. The driver was a foreman for one of the local lumbering operations, and he knew the area. He told us that he had been cruising the valley for hardwood and had found a place only a day or two before that had lots of fresh deer sign. He offered to take us as close to that spot as he could get with the jeep.

He followed a rutted tote road until it ended beside a brook, pulled up, and wished us luck. Just before he drove off he added an interesting bit of information.

“There’s a buster of a buck in here,” he said. “Our woodcutters see him every now and then, and they claim he looks like an elk. But he’s so smart and careful they’ve named him Old Eagle Eye.”

“That’s the deer I’m looking for,” I joshed. “We’ll have him out of the woods before dark.”

“I hope you do,” the foreman said, grinning. He turned the jeep and started back down the tote road, and Olive and I walked into the woods. I didn’t give his story about the big buck a great deal of thought. I’d heard quite a few rumors of that sort in my years of hunting, and most of them weren’t worth putting much stock in.

The mountains rose steeply on each side at this point, and the brook that ran down the valley was swift and noisy, swollen by rain. Olive and I followed it, moving quietly. Most of the timber was fairly open, but here and there we came to thickets of what Maine people call winter beech. It’s a scrubby and bushy type that keeps its leaves all winter. They turn brown but hang on until the swelling buds push them off in the spring.

Where it’s thick, winter beech is more difficult to hunt in than a fir thicket, for the dead leaves make the going very noisy. Olive and I came to a belt of it that reached nearly all the way across the valley. We stopped at the edge and took stands a few yards apart. It was now around 9 a.m., a very good time to catch a buck crossing from one mountain to another.

I had been standing for about 20 minutes when a twig snapped and through the brown leaves I spotted part of an antler. I couldn’t see the deer, and the antler disappeared before I could line my sights on the place where he should be. I told myself that the buck had seen me and was sneaking off.

It’s always a letdown when a deer outsmarts you that way. But the wind was in my favor, and I knew he hadn’t scented me, so I stayed where I was, moving not a muscle and hoping for the best. After a few minutes I heard another twig break. He hadn’t moved out, after all. Then brush cracked, and I heard other deer moving on both sides of him.

I had hunted deer too long to get buck fever now, but a situation of that kind, where a man can hear game he can’t see in a place he can’t work up on it, is pretty strong medicine. I admit my heart was pounding.

There was no chance for a stalk. I knew that if I tried one I’d jump the whole bunch before I could get close enough to see them. All I could do was wait.

I had hunted deer too long to get buck fever now, but a situation of that kind, where a man can hear game he can’t see in a place he can’t work up on it, is pretty strong medicine. I admit my heart was pounding.

Next I saw an antler shine again and made out a brownish-gray back. The deer went out of sight, and then I caught another glimpse but not enough to judge his size. That happened two or three times, and I realized that he was moving away.

If I wanted that buck, it was now or never. The next time I caught a patch of brown, I tried a quick shot. It was a clean miss.

The deer crashed off, and everything got quiet. For five minutes I didn’t hear another sound. Then the silence was broken by the loud thump of Olive’s .38/40.

After a few seconds, she called, “Come over here, Ransom. I’ve shot a big buck.”

For some reason, maybe because I knew that more deer were in that thicket, I didn’t answer or start toward her. In another minute I heard a loud crashing and saw this enormous buck coming straight for me.

If a deer can sneak along at a dead run, that’s what this one was doing. Though he was going flat out, he wasn’t bounding but instead was keeping his body close to the ground and his neck outstretched. I had never seen a buck do that before, not while running.

I got one good look at him where the brush thinned out, enough to realize that I had never laid eyes on such a deer. Then, 50 yards off, he swung a little to my left. I was going to have a perfect shot.

My rifle was one that very few of today’s hunters have ever heard of, a Winchester Model 1886 in .33 caliber. In Maine we used to call it a moose gun because of its knockdown power. It hasn’t been made for many years. I bought mine used when I was in my early 20’s. The thing I liked best about it was the heavy bullet, 200 grains, just right for punching through brush and then flooring a deer for keeps.

I used to guide and do other work at hunting camps, and I’ve had to trail many wounded deer. Almost every time, failure to kill quickly was caused partly by a light bullet. Any time I hit a buck with the 200-grain load from that .33, if he traveled more than 400 yards I could bet he had suffered only a slight wound. And even that happened only a few times.

(I have always believed that once a hunter gets accustomed to the feel of a rifle, he’d better hang onto it. But the barrel of my old Winchester played out a few years ago, and I couldn’t get a replacement, so I went to a Remington Model 742 in .30/06 caliber.)

The rear sight on the old .33 was a Lyman peep, and I had taken out the small center ring that morning for better sighting there in the rain and poor light. I brought the rifle up and waited for the buck to break out of the thick brush. He was about 35 yards away when I put the front bead where his neck and shoulder came together and let him have it.

He piled up in a heap. I levered in another cartridge and kept him covered. He struggled to his feet and made one lunge, making a strange noise that was half hoarse bleat, half roar. But before I could get off a second shot he went down again and it was all over. He didn’t even kick. I walked up to him and saw that he was just as the woodcutters had said. Except for his rack he looked more like an elk than a deer. Only then did I answer Olive’s hail.

“You come over here,” I called. “If you think you’ve got a big buck, I’ll show you his grandfather.”

I dressed the two deer, but it was useless to think about getting them out of the woods without help. We followed the brook back to the tote road and walked three more miles to our car. We got there just before noon, and Olive waited while I went to look for Philip. I couldn’t find him, but it wasn’t far to where my brother Ralph lived in the town of Concord, so we drove to Ralph’s place.

We ate dinner and started after the two deer with his jeep, leaving word for Philip to follow us. Ralph drove the jeep as far as where the foreman had dropped us off earlier, and he and I went the rest of the way on foot.

When we got to the kills we took time to look things over, and while we were following deer tracks through the wet leaves Ralph jumped a nice six-pointer and downed it with one shot. Now we had three deer to drag out.

We dressed his and took it down along the brook to the jeep. We found a fairly good trail, mostly downgrade, and the deer was freshly killed and not too heavy, so that wasn’t a bad chore. Next we went back after Olive’s, and that was more like work.

I don’t think anyone believed me, but nothing more was said. That night, however, just about the whole crew came to look at him, and everybody agreed that he was the biggest buck they had ever seen. All doubt about the 300 pounds seemed to vanish.

Then we tackled the big one. We cut a short maple pole and tied it to his antlers, but it was all the two of us could do to lift his head and neck off the ground, let alone drag him. We strained and heaved, panted and puffed, moved him a few yards, and gave up.

I went back to the jeep in the hope that Philip had arrived. Sure enough, he was just coming up the tote road.

He had astonishing news. His wife had killed a nice spikehorn, and he had taken a 10-pointer that would dress out at over 200 pounds. He’d shot it almost within sight of their car while they were dragging Madeline’s out. Both of those deer were now out of the woods.

Talk about luck! In less than a day five members of the Hinkley family had filled. That would go down as the best year of deer hunting we’d ever had.

Philip and I went back to Ralph, and the three of us tackled the giant buck. It was about as hard work as I have ever done. We’d skid him a few yards, rest, grunt and tug, and make a few yards more. It was pitch-dark when we finally reached the jeep.

We wrestled the buck aboard, loaded Olive’s and Ralph’s deer on top, and headed for Ralph’s place. There we put our bucks on our two cars and started for Augusta. On Sunday we skinned out Philip’s and Madeline’s and cut them up for the freezer, but we didn’t have time to work on mine.

Since 1949 our state has had a Biggest Bucks in Maine Club. I’d shot a few deer that probably would have qualified me for membership, but I had never bothered to enter them. And it didn’t occur to me at first to enter this one.

I went to work at the mill Monday morning, and somebody asked me, the first thing, if I got my deer. When I said yes, the next question was, “How big?”

“A three-hundred-pounder,” I replied.

I don’t think anyone believed me, but nothing more was said. That night, however, just about the whole crew came to look at him, and everybody agreed that he was the biggest buck they had ever seen. All doubt about the 300 pounds seemed to vanish.

A deer that big is bound to attract a lot of attention. I had so much company that night that I didn’t get him skinned, and the next day he was the main topic of conversation at the mill. I could see that one man still doubted the weight.

“We’ve got to find some scales and weigh that buck,” I overheard him say during the afternoon, “or Hinkley will claim the rest of his life that he shot a three-hundred-pound deer.”

He found scales that night, but their limit was 260 pounds, and they didn’t even come close. After the man left I told my wife, “There’s been so much said that I’d like to know myself just how much this deer weighs.”

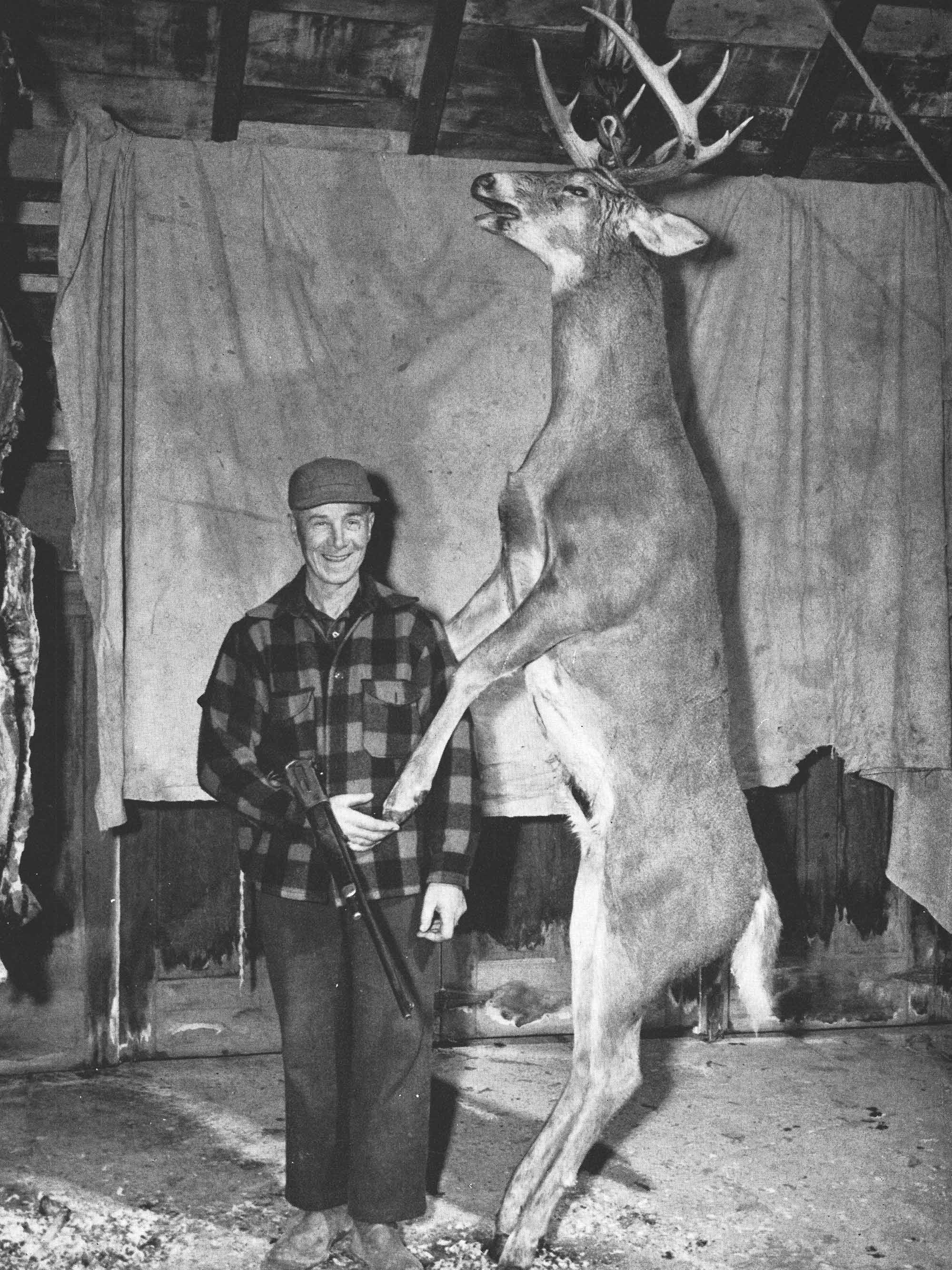

A neighbor told me that Forrest Brown, a state sealer of weights and measures at Vassalboro, north of my place, had scales that would handle the buck. On Tuesday evening, three days after I’d killed the deer, I went to see Brown. That same night, he brought portable beam scales, state certified, to my place and we put the buck on them. The scales read 355 pounds.

While we were weighing the buck my milkman, Fred Brewer, and one of his drivers, Alvin Greeley, came along. They checked the weight and offered to stand as witnesses. As things turned out, that was lucky for me.

Brown suggested that I register my trophy with the Biggest Bucks Club, so I called Roy Gray, a local game-warden supervisor, and he contacted Bob Elliot, then with the Maine Department of Game and now the state’s director of Vacation Travel Promotion.

Elliot passed the word to the Kennebec Journal. The next day’s paper ran a front-page picture and story, the buck’s fame grew, and a stream of visitors began to arrive for a look at him. The first thing Elliot undertook was to calculate the buck’s live weight. The established procedure is to add 30 percent to the dressed weight, a formula based on long study, including records of 112 deer from New York and 131 from Michigan. But because in dressing my deer I had removed the heart, and also because the buck had lost a lot of blood in the chest cavity, Bob added 20 pounds to the dressed weight before he applied the standard formula.

He came up with a live-weight figure of 488 pounds! That may have been high, but certainly the buck had weighed well above 450. And in any case, based on his dressed weight of 355 alone, he went into the records as the biggest deer ever killed in Maine.

State game men even raised the question at first of the possibility that he was a deer-elk cross, but that theory was quickly ruled out.

Had I shot the heaviest whitetail ever recorded in North America as well as the heaviest in my home state? On the basis of all available evidence it seemed likely that I had, and Maine officials thought so.

“We believe this is the heaviest whitetail ever shot anywhere,” Elliot wrote me.

Reliable weight records of big deer are not too common, partly because all scoring is now done according to antlers. In that category my buck didn’t Stack up as extraordinary. His maximum spread was 21 inches, the outside curve on both antlers measured 24 ó inches, and there were 16 points, of which 12 were over an inch long. The rack was never scored by the Boone and Crockett Club method, but I had killed deer with better racks.

To this day, however, I have not learned of another whitetail that could match mine in weight. Ernest Thompson Seton, a leading wildlife authority of past years, cited as the biggest whitetails that he knew of a Vermont buck that weighed 370 pounds before it was dressed; one from New York that dressed at 299; a third, also from New York, with an estimated live weight of 400; and one from Michigan that dressed 354. That still leaves mine the front-runner.

I have heard a rumor that a buck killed in the Rainy River country of Ontario in 1938 dressed out at 358, three pounds more than mine, but there to be no official record of it.

My story should end there, but it doesn’t. An astonishing development was yet to come.

In the next couple of evenings at least 200 people came to see the deer, among them a Maine game biologist, Jack Maasen. He made careful measurements that showed the kind of whopper I had killed. The neck girth was 28 inches, body girth behind the forelegs 47, greatest girth over the shoulders 56, and length from hind toe to tip of horns 9½ feet.

I still hadn’t had a chance to skin the buck, and the meat was starting to show signs of spoiling. Maasen wanted him mounted life-size for exhibition, but the Game Department had no funds for that, and neither did I. I hunt for venison as well as sport, so I decided to send the deer to a freezer plant for processing. Maasen offered to take him in, to save my losing time from my job.

The processing would cost eight cents a pound. There was a lot of fat and tainted meat that I didn’t want to pay for, so I got up early that morning and trimmed away fat, kidneys, diaphragm, lungs, windpipe, and a great amount of spoiled meat. When I finished I had more than a bushel of scraps.

Then the roof fell in. On Friday, six days after the deer was shot, the freezer plant put him on scales in the presence of a group of witnesses, and he then weighed almost 100 pounds less than I had reported. I was notified that Maasen had entered him in the Biggest Bucks Club at the reduced weight, after shrinkage and trimming, and the deer now stood a long way from the top of the Maine record list. The matter would be dropped and forgotten.

I was heartsick and dazed, and I was also baffled. I knew that the deer had been weighed honestly on certified scales, and I had truthful witnesses to prove it.

I was heartsick and dazed, and I was also baffled. I knew that the deer had been weighed honestly on certified scales, and I had truthful witnesses to prove it. Was it possible for him to lose as much as 100 pounds from trimming? Was that what had happened, or had some incredible blunder been made? I resigned myself to the fact that I’d probably never be able to prove it. The whole thing seemed likely to remain a mystery so far as the public was concerned.

Then one morning I picked up a Bangor newspaper, and a headline on the front page stared up at me: “Big Buck Loses Weight Fast.”

I boiled over. Not only was Maine being cheated out of a valid record, but I felt that I was being held up to ridicule. I wasn’t going to stand for that. I swore I’d vindicate myself if it took a year.

It took a little longer than that.

I went first to Forrest Brown. He rechecked his scales with official weights and found that they were absolutely accurate.

“I’ll take oath that the weight of your deer was correct,” he told me. He did too, giving me a certified statement in his capacity as sealer of weights and measures. And Fred Brewer and Alvin Greeley, the milkmen, signed that statement as witnesses.

Next Richard Esty, a local meat cutter who had advised me how much of the deer to trim away, gave me a letter in which he said, “The parts that I advised you to remove would very easily shrink the weight 75 to 100 pounds.”

Bud Leavitt, outdoor writer for the Bangor News, came out flatly on my side. Even the freezer plant came through with a letter to Bob Elliot saying, “The deer arrived here several days after being shot, with all fat, kidneys, etc. removed, and, as do all deer, it had dried out considerably.”

In the meantime I was getting letters from as far away as New Jersey, Indiana, and even California, from people who had seen a picture of the deer and on the basis of the picture accepted my claim at face value. They believed that I had an all-time record. I pressed my claim with the Game Department without letup, and Roy Gray, the supervisor of game wardens who had first brought the buck to the department’s attention, sided with me, saying that in his opinion the weight at the plant with the carcass trimmed had no bearing on the original record.

In late November of 1956, a few days over a year after the controversy first erupted, it was settled completely in my favor.

Read Next: The Real Story Behind the Casey Brooks Bull, the Pending World Record Elk

“We have decided to ignore the second weighing and accept the original figure of Forrest Brown as official,” Bob Elliot notified me. “We believe you acted in good faith, and although the buck was not weighed by a game warden, Mr. Brown was an official sealer of weights and measures. We accept your belief that the meat trimmed away between the two weighings was enough to account for the difference.”

The mystery of the Hinkley deer — if mystery it ever was — had been officially solved. That monster whitetail would stand in the records now for keeps, at the dressed weight that I had originally claimed. So far as I know, that leaves a Maine deer at the head of the list, the heaviest ever shot anywhere. That was what I really wanted all along.

Read the full article here